When Self-Checkout Turns Shoppers Into Economists

What looks like a sudden surge in theft turns out to line up closely with something economists have understood for a long time.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

There’s a moment at self-checkout that feels familiar to almost everyone.

You scan an item. The machine beeps. You place it in the bagging area. Then you look down at the next thing in your cart. You know how much it costs. You know how tight your budget feels. And you have a pretty good sense of how closely anyone is watching.

You pause.

Most of the time, that pause is barely noticeable. You scan the item and move on. But sometimes it stretches just long enough for a quick mental calculation. This isn’t a moral debate so much as a practical one. What do I gain if I skip this? What’s the chance anyone notices? What happens if they do?

We make cost-benefit decisions like this all the time. We weigh tradeoffs when deciding whether to wait in a long line, pay extra for convenience, or risk cutting it close for a meeting. Standing at self-checkout, the logic isn’t any different.

And increasingly, people are acting on it more often than they used to.

Headlines about rising theft at grocery stores and retail chains have been piling up. More items are locked behind glass. More attention is focused on self-checkout. What looks like a sudden surge in theft turns out to line up closely with something economists have understood for a long time.

The pause, revisited

Self-checkout absolutely makes mistakes easier. Anyone who’s balanced produce, barcodes, and a touchscreen knows that. Plenty of people walk away and only later realize they missed something.

That’s not what economists mean when they talk about crime.

To understand what economists are interested in, we have to go back to that pause at the register. You haven’t scanned an item yet, and you’re deciding what to do next. At that point, we’re no longer talking about accidents. We’re talking about choices.

The logic people walk through in that moment is surprisingly consistent, even if they’d never describe it this way.

What do I gain? That part is obvious. You leave with the item and save a little money.

What happens if I’m caught? Is it embarrassment or something more serious?

What’s the chance I get caught in the first place? How closely is anyone watching, and how confident am I that this will go unnoticed?

Those last two questions matter because they introduce probabilities into the decision. Together, they determine the expected cost of theft. Not just what could happen, but how likely it is to happen.

Retailers expect some baseline level of theft, often referred to as shrinkage. It’s built into the prices we pay, even if we’d never think of stealing. But if theft levels are changing, it means something in that calculation has changed.

Either the benefit got bigger, the punishment got smaller, or the likelihood of getting caught fell.

Meet Gary Becker

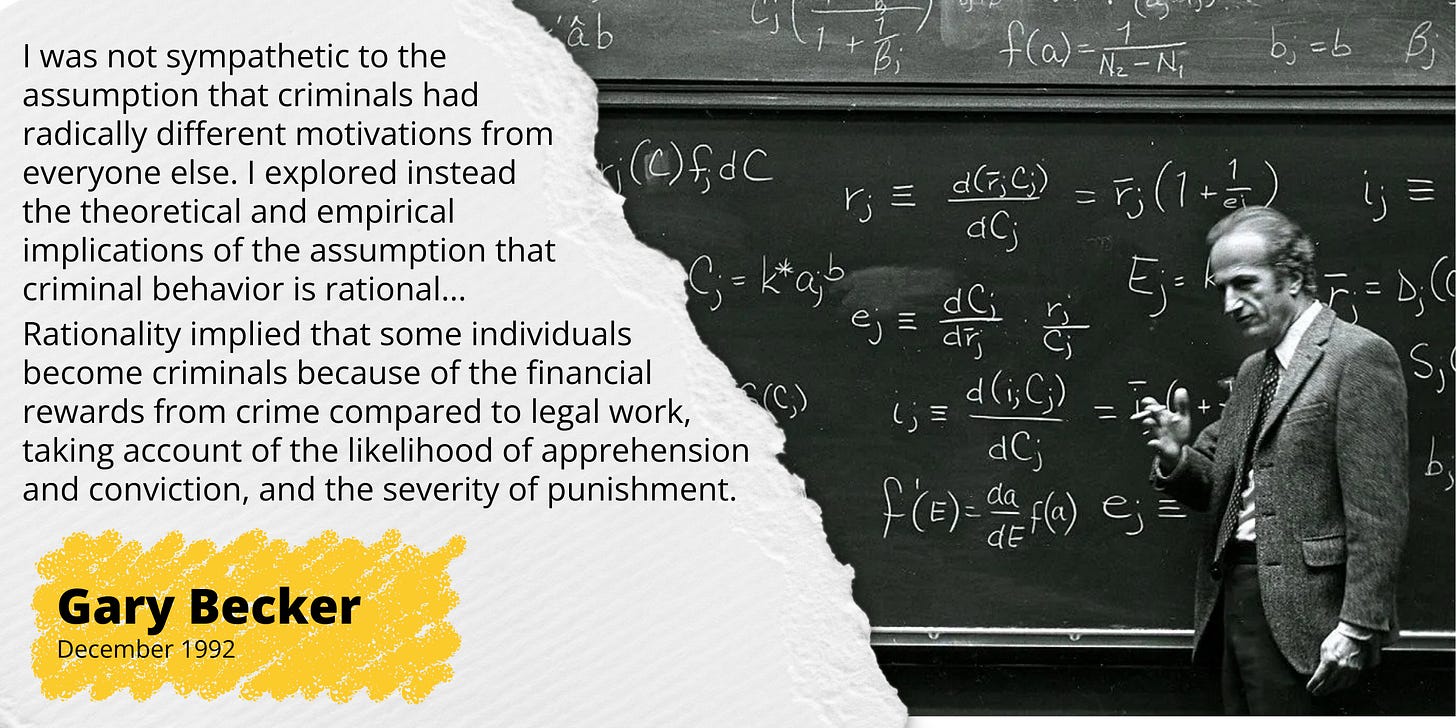

This way of thinking didn’t come from retailers or crime labs. It came from an economist who was willing to ask an uncomfortable question.

Gary Becker was a Nobel Prize–winning economist who spent his career applying economic reasoning to areas most people thought economics didn’t belong. Crime. Education. Immigration. Family decisions. Discrimination.

At the time, this approach was controversial. Many scholars assumed criminals were fundamentally different from everyone else.

Instead, he asked what would happen if we assumed criminals respond to incentives the same way everyone else does. That they weigh tradeoffs. That they respond to prices, risks, and rewards. That they make decisions using the same basic logic we use when choosing a job, a school, or whether something is worth the hassle.

That framing turned out to be revolutionary.

What changed in the calculation

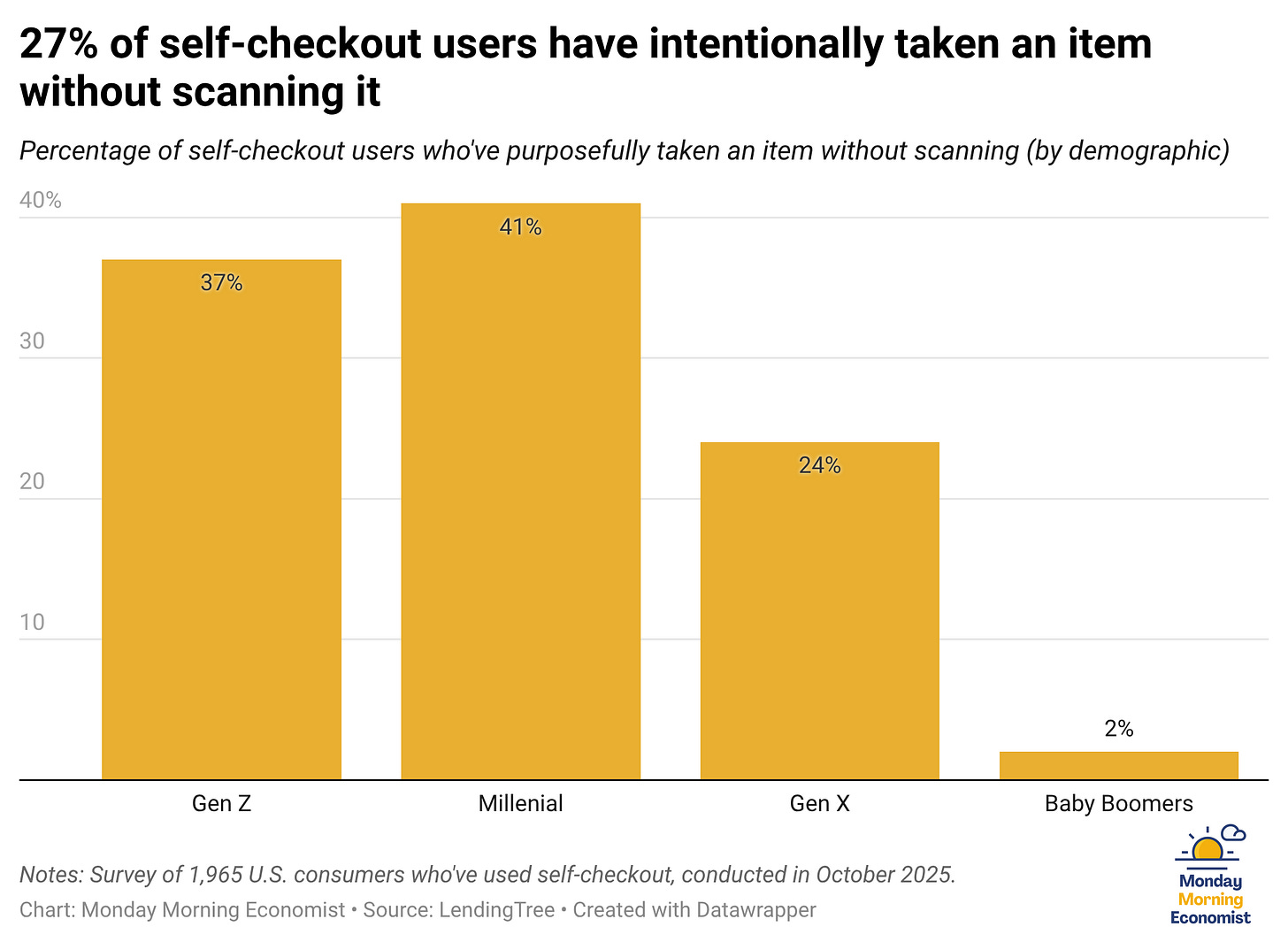

A recent LendingTree survey found that 27% of self-checkout users admit to intentionally taking an item without scanning it, up from 15% just a year earlier. That’s a sharp change in a short period of time. When behavior moves that quickly, economists start looking for changes in incentives.

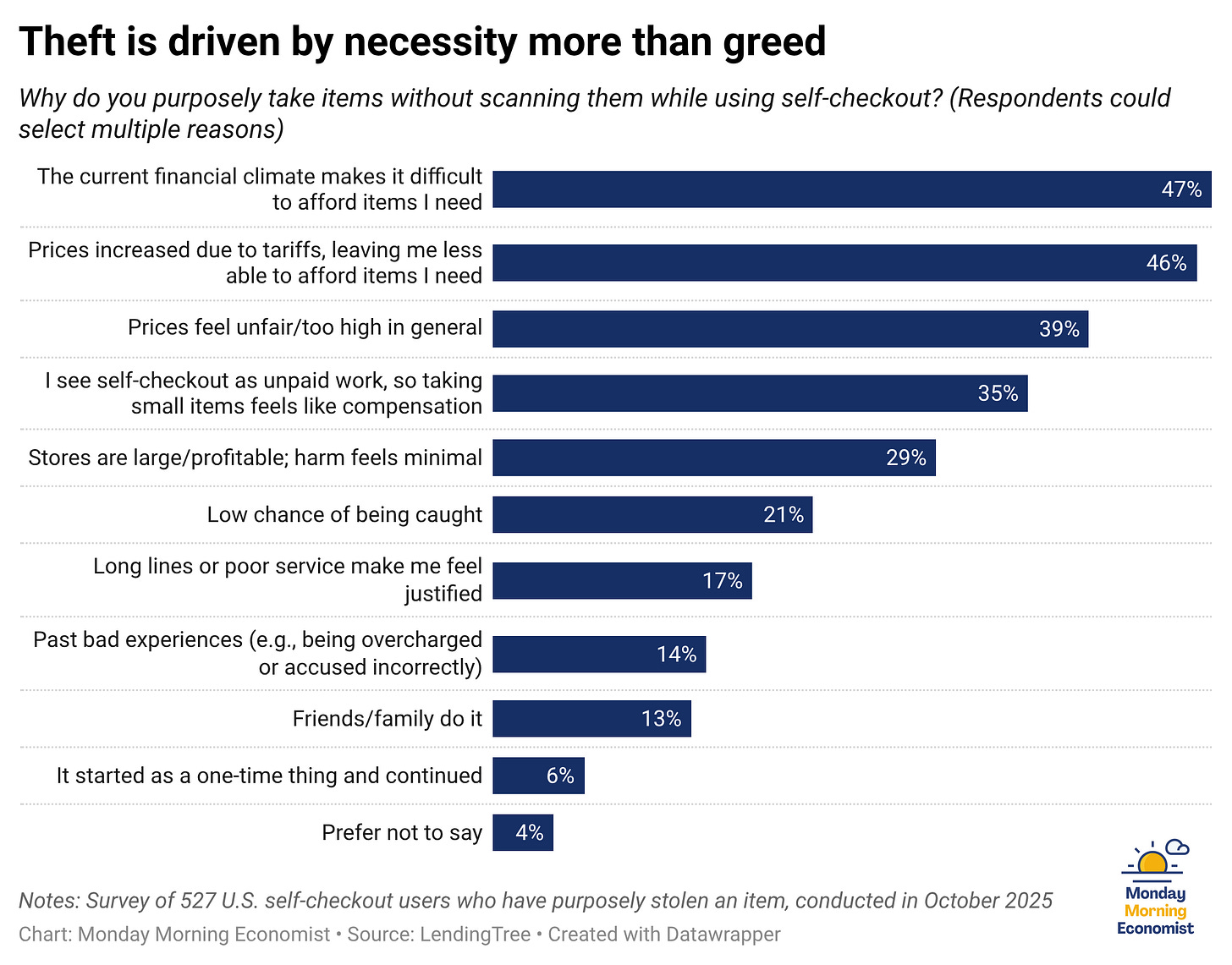

The explanations are pretty straightforward on the benefits side of the equation. Survey respondents who admitted to stealing pointed to ongoing financial stress and high prices. The affordability crisis has been a slow, nagging pressure with no clear end in sight.

As prices rise and budgets feel tighter, the payoff from skipping a scan increases, too. The same item provides more relief than it would have a few years ago. Under Becker’s framework, that alone is enough to increase theft at the margin.

But the survey didn’t stop there.

Retailers have been pushing back. They can’t easily change punishments, but they can raise the likelihood of getting caught. And by many accounts, they have. Among people who admitted to intentionally stealing, 42% said it has become more difficult to do so over the past year, citing more employee monitoring, more cameras and AI-assisted systems near kiosks, and more sensitive weight and scale checks.

That’s what makes this story so interesting.

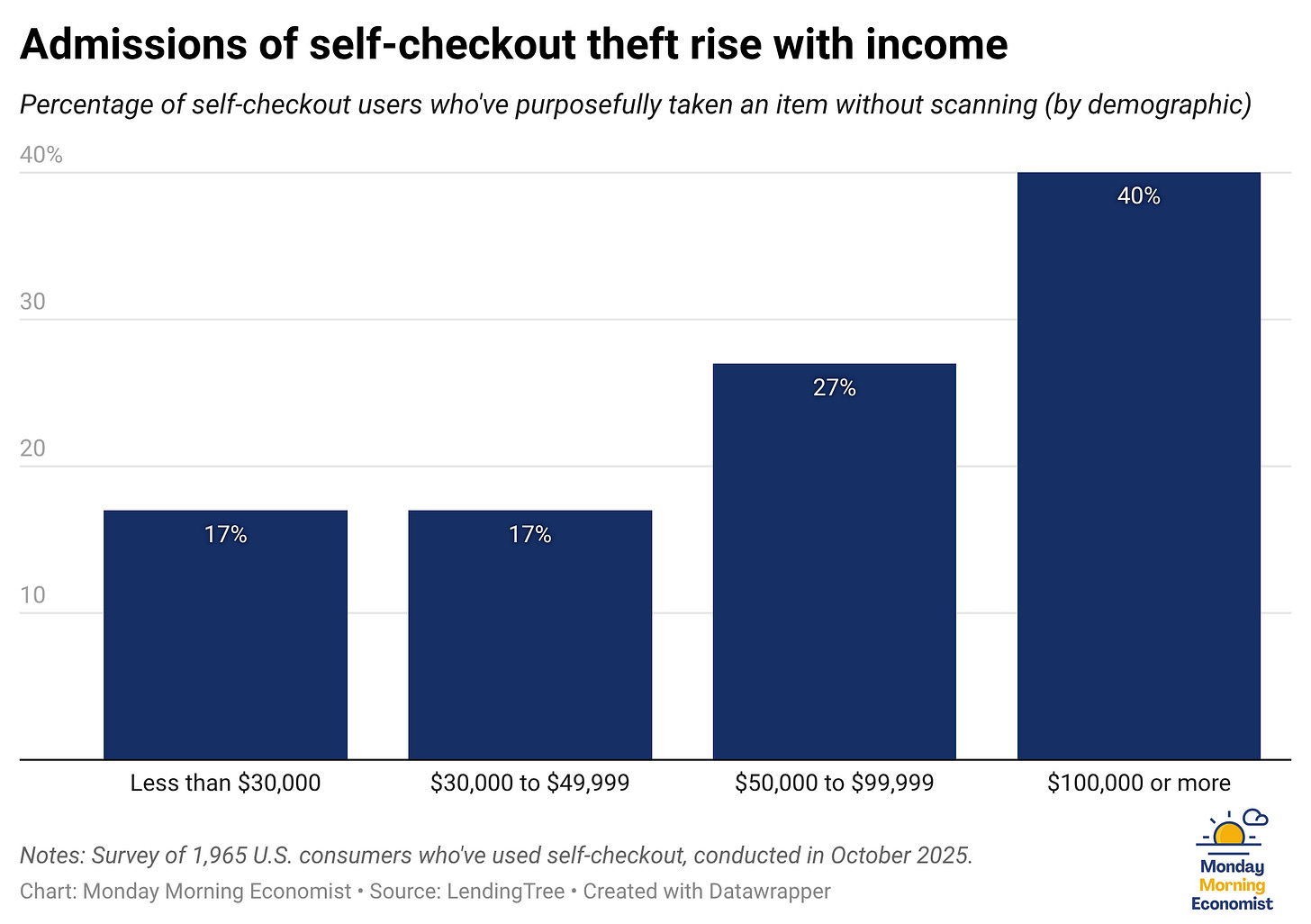

Even as people say it’s become harder to steal, more people are doing it. Under the rational model of crime, that tells us something important. When both the benefit and the expected cost are rising, but theft still increases, the benefit must be rising faster than the costs.

In simple terms, higher prices are doing more to change behavior than increased monitoring is doing to deter it. The affordability pressure facing many shoppers is strong enough to outweigh a higher risk of getting caught.

Final Thoughts

What stands out most in the survey isn’t just how many people admit to stealing. It’s how conflicted they feel afterward. Some regret it. Some don’t. Many say they’d do it again, even knowing the risks.

The rational model of crime isn’t a moral judgment. It’s a lens that helps explain why that pause has become more common. It doesn’t excuse what happens next.

Still, the pause belongs to you. Right there at the register. In that quiet moment when no one is watching, the math feels tempting.

Understanding the economics won’t make the choice easier. But it might make that pause a little harder to ignore the next time you’re at the store.

If this made you think a little differently about that pause at the register, consider sharing it with a friend. Especially the one who’s always watching cop shows and wondering why people keep committing crimes even when the risks seem obvious.

Nearly 40% of grocery store registers in the U.S. are self-checkout kiosks [Capital One Shopping Research]

Roughly 30% of all grocery store transactions were from self-checkout lanes in 2021, almost double the amount in 2018 [The Food Industry Association via Babson Thought & Action]

Shoppers with 50 items in their cart had a 60% chance of having at least one un-scanned item, while shoppers with 100 items had an 86% chance of error [Groery Dive]

55% of those who’ve deliberately stolen at self-checkout say they think they’ll do it again [LendingTree]

Projections indicate that by 2030, over 24,000 stores will offer self-checkout [The Payments Association]

I wonder if there is a study that shows how much firms internalize these costs. We could see a negative impact on other shoppers, even if it's marginal. The people who don't steal would be punished, while the people who do steal wouldn't be. It might even incentivize more people to steal -- especially since now it's looking like the social cost is lower as well.

I am comfortable now, but if I was still poor I'd probably think harder. My version of pausing now usually means I change my mind and don't buy the item. And if I get home and realize I missed something, I just think thats what they get for making me do their work.