The Price of Cutting in Line

Apps are turning simple night out or a trip to a theme park into a lesson in economics

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 5,200 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

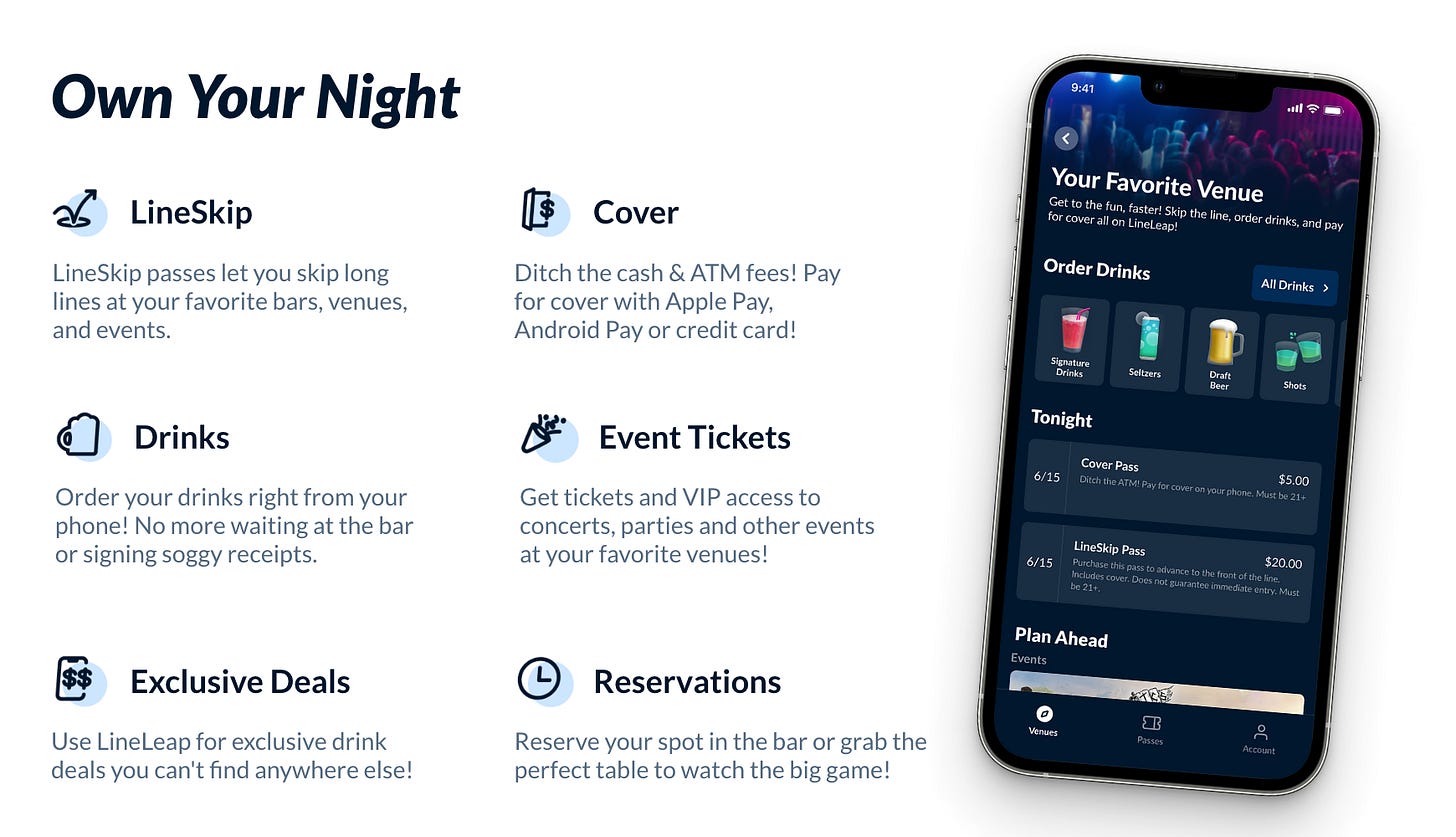

In college towns around the United States, a classic economic conflict plays out every weekend against the backdrop of thumping bass and neon lights. It’s a place where students, smartphones in hand, engage in a very modern version of an age-old marketplace tug-of-war: balancing efficiency with equity. The protagonist in this nightly drama is LineLeap, an app that lets bargoers pay a premium to jump ahead in long lines at popular spots. While some love the convenience and time saved, others feel excluded while they wait in line counting minutes and dollars.

LineLeap is part of a growing trend affecting not only the nightlife in college towns but also airport security and amusement park lines nationwide. By paying a premium, some people bypass the long wait—a boon for them but a source of frustration for those unwilling or unable to afford the extra cost. This shift from a democratic "first come, first served" model to a monetized system has ignited debates among students over fairness and highlighted a broader business strategy. In environments plagued by lengthy lines, offering a fast pass has become a profitable method for tapping into consumer impatience and their readiness to pay for the luxury of time saved.

The Efficiency–Equity Tradeoff

Arthur Okun, an economist known for articulating the trade-off between efficiency and equity, might have found the situation unfolding at college bars a perfect illustration of his theory. In the world of services like LineLeap, efficiency is king. It helps companies leverage their limited space and finite hours of the night to increase profits. Those patrons who place the highest monetary value on immediate entry—demonstrated through their willingness to pay—are served first. This model not only boosts revenue from the premium charged for access but theoretically leads to an optimal distribution of the scarce spots inside the bar based on peoples’ willingness and ability to pay.

In this scenario, however, equity is sidelined in this pursuit of efficiency. The traditional system, where entry was granted on a first-come, first-served basis, feels like a more equitable distribution of access to many people. This method valued time—everyone had an equal shot if they were prepared to wait. But with the advent of services like LineLeap, a person’s financial capacity now tops time spent in line. Thus, as Okun suggested, enhancing efficiency in economic transactions often comes at the expense of fairness.

Allocation Methods

The challenge of distributing scarce resources—whether it’s a seat on a plane, a table at a restaurant, or entry to a bustling bar—is a fundamental problem that businesses must solve. Economists often point to three primary methods of allocation: price, queue, and lottery, each addressing efficiency and equity differently.

Allocation by price, as demonstrated by LineLeap, is praised for its efficiency. By allowing those who value immediate entry most (and are willing to pay for it) to skip the line, it ensures that resources are used by those who presumably derive the highest utility from them. However, this method often comes under fire for its lack of equity, as it favors those with greater financial resources.

Conversely, allocation by queue involves the age-old practice of waiting your turn. It’s celebrated for its fairness. Everyone has an equal opportunity to access the resource simply by arriving early and waiting, making it more equitable but often inefficient. For individuals who value their time, the opportunity cost of standing in line can outweigh the benefit of the service itself.

Lastly, a lottery system introduces a random element to allocation, making it inherently equitable by giving everyone an equal chance to win access. However, its randomness can be inefficient, as it does not discriminate between those who might place a high value on immediate access and those who do not.

Beyond the College Bar

The trend of prioritizing efficiency through monetization extends beyond the lines outside your favorite college bar. Across various industries, businesses are shifting towards models that cater to convenience, often at a premium. In airports, for example, services like Clear and priority boarding options let travelers bypass traditional security lines or board the plane first, for a fee.

The restaurant industry has also embraced this shift. Reservation platforms such as Resy and OpenTable capitalize on the demand for certainty and convenience by allowing patrons to reserve a table for a fee, avoiding the unpredictability of walk-in waits. This not only improves customer satisfaction for those who value planning but also helps restaurants manage their seating more effectively.

Similarly, theme parks have popularized line management through systems like Disney’s old FastPass program. This service allows parkgoers to book their spot at popular attractions at designated times instead of waiting in line. While these passes come at an additional cost, they highlight how long we’ve been moving toward systems that prioritize efficiency.

Final Thoughts

The debate surrounding monetized line systems often centers on the social values they reflect and the kind of society they perpetuate. What does it say about us when the ease of a night out or the joy of a theme park visit is contingent upon one’s financial means? In today’s economy, price increasingly dictates priority

For college students, the advent of paid line-skipping apps like LineLeap serves as a real-life lesson in economics. It’s a good reminder that the economic theories of resource allocation methods are not confined to textbooks or lecture halls.

There are 42,223 undergraduate students enrolled at Penn State’s University Park campus in State College, Pennsylvania [Penn State]

The standard price for an annual Clear membership is $199 [Nerdwallet]

When people are waiting in a long line, 65% of people say they move ahead as soon as there is space behind the person in front of them [YouGov]

In 2023, more than four million people enrolled in TSA PreCheck, bringing the total number of active TSA PreCheck members to more than 18 million [Transportation Security Administration]

Single Pass Lightning Lanes at Disney World cost roughly between $10 and $25 for one person to ride the ride one time, depending on the ride and day [Mouse Hacking]

My frustration with Clear and TSA Pre-check is that the security line at airports is not really a choice people can make. The TSA is a government agency and airports have had 20 years to figure out a way to efficiently move travelers through security. I feel like they have kept it annoying and inefficient on purpose in order to force people to buy pre-check or clear. If the government is requiring airports to have a certain level of security, they should remove the economic incentive to keep it as terrible as possible by requiring airports to get people through security in 30 minutes or less.