How Sandwiches Can Explain 100 Years of Economic Growth

The simple sandwich can help explain how everyday life has changed over the last century

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Let’s start with a classic economics thought experiment. Would you rather be the richest person in the world 100 years ago, or an average person today?

There’s no “right” answer. But it’s the kind of question economics professors love to ask on the first day of class, because it gets students thinking: What do we really mean when we talk about progress?

It’s easy to list the big changes like smartphones, the internet, and modern medicine. But economic growth also appears in small places. Like your lunch. So here’s a slightly different version of that same question:

Would you rather eat a typical sandwich from the 1920s or one from your local deli today?

Let’s tackle this question with the help of Barry W. Enderwick from Sandwiches of History. You may have seen his videos popping up on your social media feeds over the past few years. He’s the guy who recreates sandwiches from old cookbooks that were mostly written for everyday home cooks in the early 1900s. His videos are part history lesson, part recipe test, and part reminder of how far we’ve come.

When you stack up a century of economic growth that affects your typical lunch (e.g., better refrigeration, safer food, global trade, and yes, pre-sliced bread), you start to realize that even something as ordinary as a sandwich can tell a story about progress.

Economists usually measure growth with GDP charts and productivity stats. Today, we’re measuring it in mustard.

Wait... Sandwiches?

Yes, we’re actually talking about the same sandwiches many of you eat for lunch on most days. It turns out that this everyday food reveals a lot about how much our world has changed.

Let’s meet Barry, creator of Sandwiches of History. He posts his videos across a lot of platforms, but his largest followings are on TikTok and Instagram. He brings early‑20th‑century cookbook sandwiches back to life and adds a modern upgrade at the end. Some tastes surprisingly good. Others? Less so. But all of them give us a snapshot of the ingredients and cooking methods people used in the past.

Barry isn’t just a content creator. He’s a published author, too! His cookbook takes a few of the most compelling recreations and modernizes them for today’s kitchen, creating a delicious timeline of sandwiches.

We’ll select a few of Barry’s most revealing videos to show you what a typical sandwich looked like over the past 100 years. As you watch, consider how you make your sandwiches today. The twist isn’t about complexity. Modern sandwiches aren’t necessarily harder to make. Instead, they’re often much easier thanks to economic progress.

Perhaps, that’s the real sandwich story here. It’s not just how sandwiches have changed, but how much simpler it has become to eat well without being rich or lucky or living near a major port city. If you haven’t met Barry before, take a minute to let him introduce himself:

A Century of Growth, Measured in Sandwiches

You don’t need a graph of GDP or a textbook chapter on labor productivity to understand how much everyday life has improved over the past century. Perhaps, you just need a sandwich. Let’s start with the foundation: bread.

Flip through old sandwich recipes, and you’ll see the same few options again and again: whole wheat, brown bread, Boston brown, and graham bread. That was the standard rotation. If you weren’t baking the load yourself, you were buying full loaves and slicing them at home. Pre-sliced bread didn’t hit store shelves until July 1928. Yes, that’s where the “greatest thing since sliced bread” expression comes from.

Today? Your bread options stretch entire aisles at some grocery stores. Sourdough, ciabatta, multigrain, rye, brioche, gluten-free, keto, and more. It’s all there. And it’s pre-sliced, bagged, and shelf-stable for days. That variety is the result of a century’s worth of advances in food processing, packaging, storage, and transportation.

Then there’s refrigeration. A turkey sandwich with mayo is a lunch staple now. But in 1920, it could be a health risk. Without reliable access to ice or electric refrigeration, ingredients like deli meats and dairy products were tricky to store safely. Spoilage was common. Most households simply avoided them unless they were freshly made and quickly eaten.

Today, over 99% of U.S. households have a refrigerator. Most also have a microwave, a freezer, and a pantry full of condiments that would’ve required an entire weekend to prepare a hundred years ago. You can now make lunch in a few minutes without thinking twice about food safety.

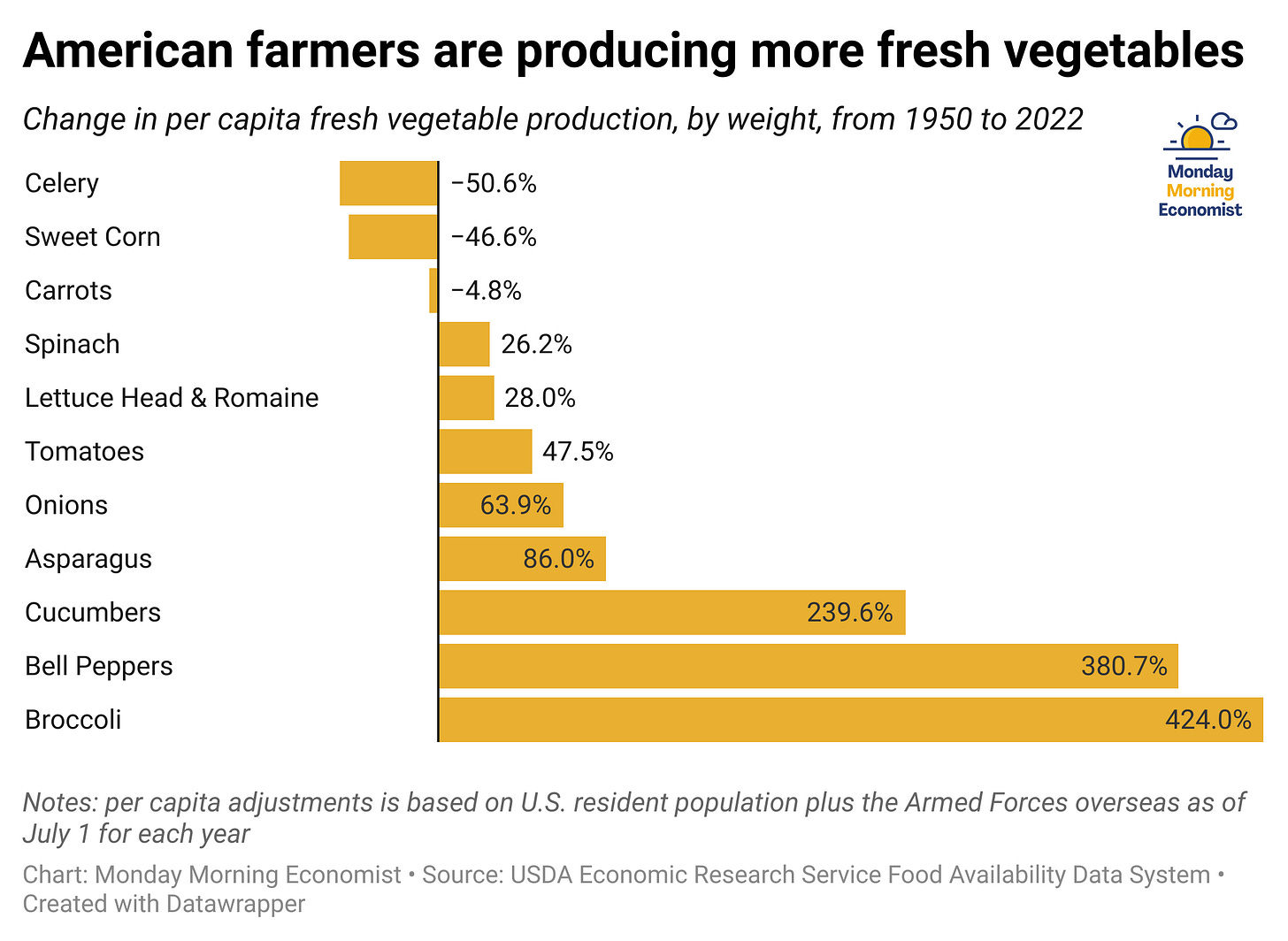

And then there’s the actual ingredients. In 1920, access to fresh vegetables was seasonal because they had to be. A tomato sandwich in January? Not unless you had access to a hothouse grower or were willing to splurge. The same story holds for lettuce, cucumbers, and peppers. Today, you can get tomatoes from Mexico, lettuce from Arizona, and cucumbers from Florida in nearly any store, any time of year.

That’s not one of the impacts of climate change. It’s a mix of international trade, cold storage, and supply chain infrastructure that’s quietly made our food world global. According to the US Food and Drug Administration, 55% of fresh fruits and 32% of fresh vegetables today are sourced from abroad.

None of this probably feels revolutionary when you’re standing in front of your fridge trying to figure out what you want to eat. But the gains add up quickly. Today’s average sandwich, made with hastily assembled sliced bread, pre-washed lettuce, deli meat, and store-brand mayo, is the product of a century of innovations that made things safer, faster, and more affordable.

And you don’t have to be wealthy or live in a major city to enjoy it. Just hungry.

How Trade Expanded Your Lunch Menu

Refrigeration made sandwiches safer. Trade made them interesting. Today, you can walk into just about any grocery store, even in a small town, and find gochujang, za’atar, harissa, or tahini. You can head home, open a recipe from a cuisine you’ve never tried, and cook a dish that would have baffled your grandparents. That kind of culinary access is so normal now, we forget how recent it is.

That wasn’t the case 100 years ago. Not because people didn’t crave variety, but because the global systems to deliver it didn’t exist yet. Early trade was mostly about raw materials, things like cotton, lumber, and sugar. While we romanticize old trade routes like the Silk Road, the scale and speed of modern globalization have changed what’s possible in everyday kitchens.

The shift didn’t happen all at once. After World War II, returning soldiers brought home new tastes, and American supermarkets began to evolve. The “international” aisle emerged in the 1950s and never looked back. In 1975, the average supermarket carried around 9,000 products. Today, it’s closer to 47,000. A large share of that growth has been international ingredients.

The produce section tells a similar story. In 1980, the average grocery store stocked about 100 different fruits and vegetables. By the early 1990s, that number had more than doubled. Avocados, bok choy, and mangoes were once considered exotic, but are now weeknight staples.

Back in the 1920s and 1930s, recipes for things like “Italian Dressing” or “Russian Sandwiches” often had little to do with their namesakes. The ingredients included things like boiled eggs, pimentos, mayonnaise, and American mustard. They were familiar at the time, not foreign.

The practice of exoticism in naming likely helped people who would never be able to travel, let alone travel internationally, make for themselves or others a sandwich with an exciting name. Imagine being in a small town in America in 1920 and being able to enjoy the “Japanese Sandwich” even if it had zero to do with Japanese cuisine. Back then, the names were aspirational. Today, the flavors are real.

Globalization, for all its complications, helped drive extraordinary economic growth and lifted millions out of poverty. And for the average American? It brought the world to the dinner table. What economists call gains from trade show up not just in GDP, but in your condiment shelf. Access, variety, and affordability are all made possible by exchange.

So when Barry “plusses up” a sardine sandwich with sriracha mayo or adds gochujang to a retro tuna melt, he’s not just improving the taste. He’s showing how far we’ve come, and how much wider the lunch menu has gotten.

Final Thoughts

Measuring economic growth with sandwiches might sound silly, but sometimes the biggest changes are easiest to see in the smallest places.

In the last hundred years, economic progress has reshaped how we store food, where we get ingredients, and how we learn to make something new. A sandwich that once took hours to prepare with limited, seasonal ingredients can now be thrown together in minutes using components from around the world.

That’s what makes Sandwiches of History so compelling. Barry brings back recipes from a time when “variety” meant choosing between graham and brown bread and when a tomato in January was a luxury.

A century ago, you couldn’t pull a screen from your pocket to watch someone revive a century-old sardine sandwich. You couldn’t scroll through comments for variations. You couldn’t order a sauce from Japan and have it delivered by the weekend.

So the next time you open your fridge, take a closer look at the sauces you have on that one shelf that is packed with way too many bottles. If you see sambal, za’atar, or sriracha sitting next to your ketchup and mustard, you’re holding a quiet reminder of how much the world, and your lunch, has changed.

If this made you think differently about what’s in your fridge (or your lunchbox), consider sharing it with a friend. After all, economic growth is easier to understand when you can taste it. And be sure to follow Barry on TikTok and Instagram to explore more sandwiches from the past!

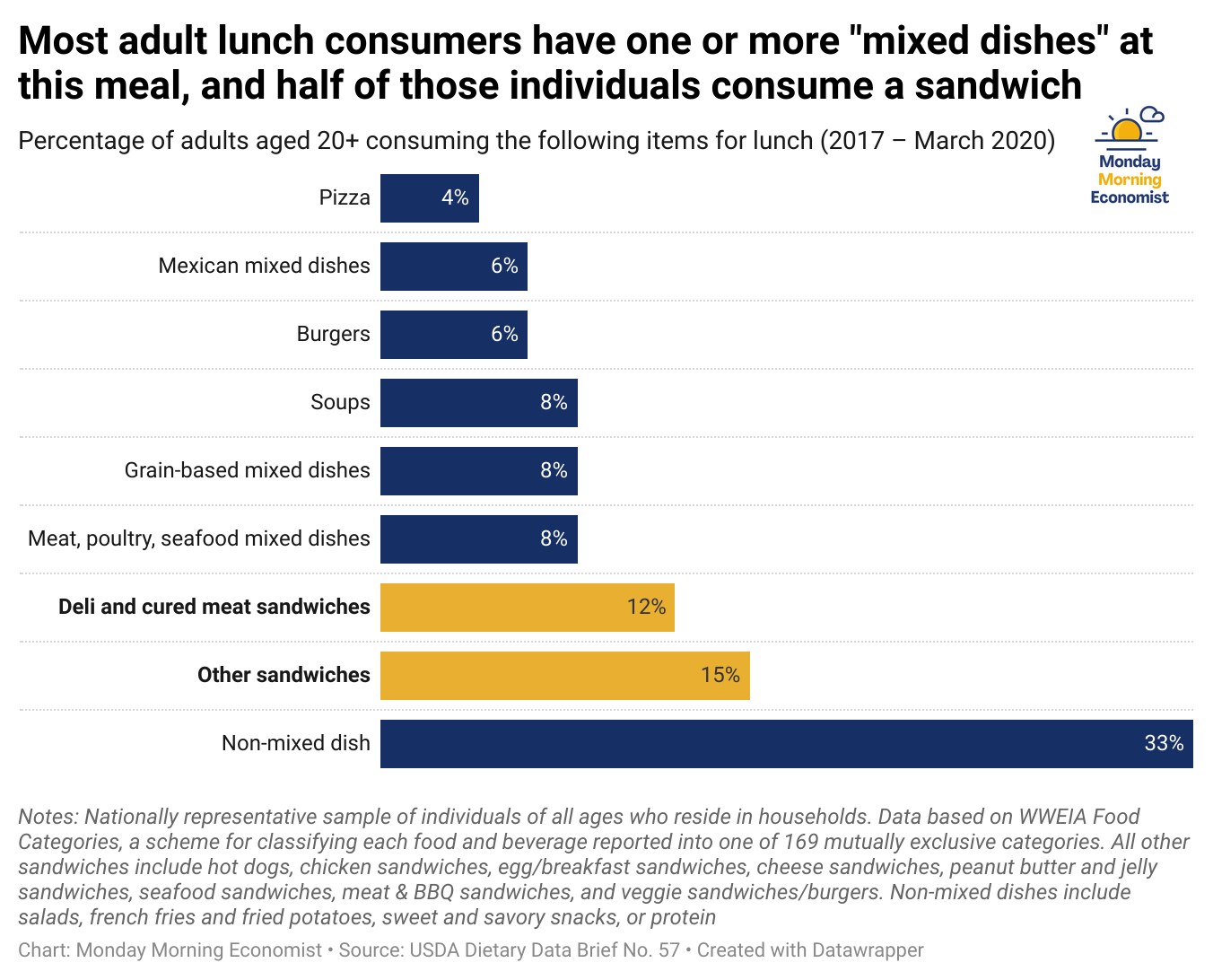

Two-thirds of adult lunch consumers have one or more “mixed dishes” at this meal on the intake day, and half of those individuals consume a sandwich [USDA Dietary Data Brief No. 57]

The baking industry employs almost 800,000 skilled individuals [American Bakers Association]

At the start of the 1930s, just 8% of American households owned a mechanical refrigerator. By the end of the decade, it had reached 44% [Pacific Standard]

In the United States, 42.53 million houses have two or more refrigerators [U.S. Energy Information Administration]

The three condiments foodies were more likely to cite as underrated compared to the average American were Sriracha (108% more likely), Hoisin sauce (92% more likely), and ketchup (66% more likely) [YouGov]

In a way the amounts of meat we include today shows how far society has come. Meat use to be a rarity on sandwiches in far smaller amounts. Now it isn't a good one unless there is a lot of meat

Another great post. I like the macro ones.