The 18-Inning Lesson in Economics

A World Series marathon gave economists a perfect example of marginal thinking and the sunk cost fallacy.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

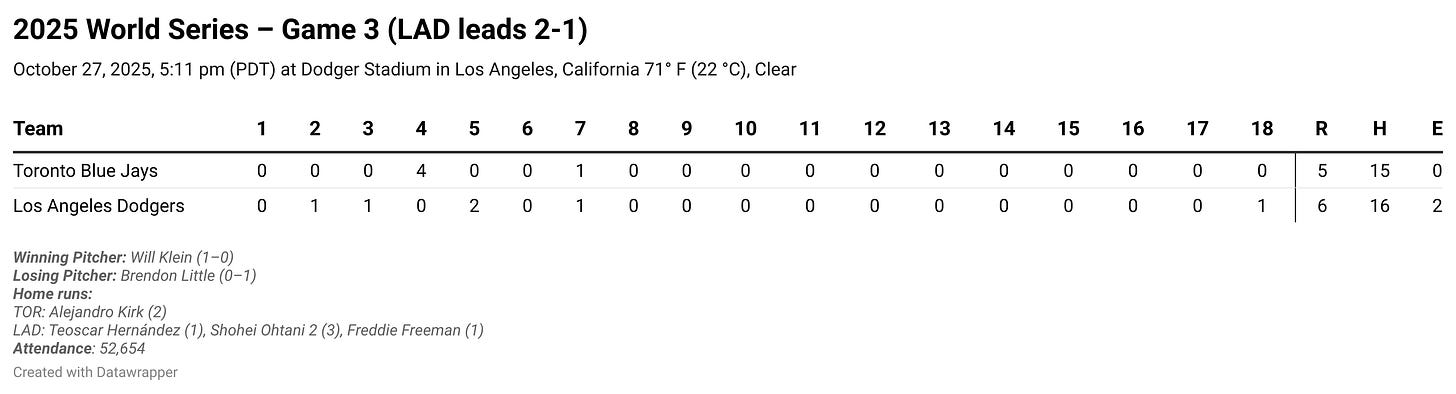

By the 18th inning of Game 3, it was nearly 2 in the morning on the East Coast. The Dodgers and Blue Jays had been locked in a 5–5 tie for hours, trading outs, hits, and long commercial breaks. Millions of viewers at home were fighting sleep, remote in hand, wondering whether to stick around for one more inning or call it a night.

Full disclosure: I wasn’t one of them. I caught up with the highlights the next morning.

The World Series is over now, but Game 3 was a great one for those interested in how people make decisions. The game was one of the longest by time and tied for the most innings in a postseason game. And despite all the decisions made on the field that night, the most interesting ones were made by the people sitting at home, deciding whether to keep watching.

The Economics of One More Inning

According to Fox, viewership for Game 3 peaked at 13.17 million as the game went into extra innings around 11:30 p.m. Eastern. At that moment, millions of fans were facing the same question: Should I watch one more inning or go to bed?

That’s what economists call a marginal decision. It involves weighing the additional benefits and additional costs of doing just one more thing. It wasn’t a commitment to stay up until the end. Instead, it was a decision to watch one more inning of baseball.

Every inning carried an opportunity cost, the value of what viewers gave up when they made their choice. Staying tuned in meant sacrificing sleep, rest, or productivity the next day. Turning off the TV meant missing the chance to see history happen live. For those who kept watching, the excitement outweighed the exhaustion. Well, at least for another inning.

That’s how economists think about “how much” decisions. Each inning was a chance for fans to pause and recalculate their costs and benefits. Economics can’t say what’s right for everyone, but it can help people think more clearly about why they choose what they do. A rational decision means continuing to watch only if the marginal benefit (the thrill of the game) exceeds the marginal cost (lost sleep and groggy mornings).

By the time Freddie Freeman ended the game in the 18th inning, about 8 million viewers were still tuned in.

To be fair, that number isn’t a perfect measure. We don’t know how many TVs stayed on while their owners dozed off in recliners across the country. As some viewers tuned out on the East Coast, others on the West Coast may have tuned in.

Still, the data tell a clear story: millions of people stayed up long past midnight to see how it would end. The question is, were they making a rational decision or falling for a familiar economic trap?

Why We Struggle to Walk Away

If you were one of the 8 million people still awake at the end, ask yourself why. Did you pause after each inning to decide if you wanted to keep watching? Or did you stay because you’d already watched 17 innings and couldn’t stop now?

If it’s the second one, congratulations! You’ve fallen for the sunk cost fallacy.

Once the 17th inning came to a close, the hours you’d already spent watching the game were long gone. You weren’t getting those back. A rational decision-maker wouldn’t factor that time into what to do next. The only question that mattered was whether watching another inning was still worth it at that moment.

But that’s not how most people think. We hate the idea of wasting things, so we double down instead. We stay through bad movies, finish meals we don’t want, and, yes, watch baseball until two in the morning simply because we’ve already made it that far.

Game 3 offered a perfect, bleary-eyed reminder of how hard it is to let sunk costs go, and how often they keep us in the game long after we should have turned off the TV.

Final Thoughts

If you’re still reading, I hope it’s because you think the marginal benefit of this last section outweighs the marginal cost of finishing it, and not because you’ve already made it this far and might as well see how it ends.

If it’s the latter, did you not just read what we said about sunk costs?

The same decision-making that kept viewers glued to their screens also played out in the stands at Dodger Stadium. Fans at Dodger Stadium faced the same question: Do we stay for one more inning, or is it time to head home?

CBS Los Angeles spoke with a few of them afterward, including one Dodgers fan who stayed until the end with his father. “We’re sticking this out,” he said. “You don’t get to go to the World Series often. As fans, it’s a gift to be able to go to a game like this.”

That’s not irrational. It’s just a different calculation. For some fans, the chance to share a once-in-a-lifetime experience outweighed the exhaustion that came with it. But not everyone saw it that way. When asked about coming back for the next night’s game, another fan said they wouldn’t be back because “We already saw a doubleheader.”

Whether in the stands or on the couch, Game 3 gave everyone a crash course in economic thinking. Each inning forced a choice: focus on what’s already been invested, or decide based on what comes next.

So if you stayed up until 2 a.m., I hope it was because each inning felt worth it, and not because you’d already made it that far. And if you went to bed early? Well, that might have been the most rational play of the night.

If you enjoyed this post, share it with the friend who won’t stop bragging about staying up for all 18 innings or the one who proudly fell asleep and missed history. Either way, they made an economic choice worth talking about.

Game 3 of the 2025 World Series took longer than the game time of the entire 1939 World Series [OptaStats]

The combined U.S. and Canadian average was 18.73 million through the first three games, up 25% from the 2025 all-U.S. World Series [Sports Media Watch]

There were 609 pitches thrown, 48 more than in any other postseason game since at least 2000 [Major League Baseball]

The longest game in MLB history lasted 26 innings and might have gone even longer if it hadn’t been called on account of darkness [Major League Baseball]

The World Series champion receives 36% of the postseason players’ revenue pool, the runner-up 24%, each League Championship Series loser 12%, each Division Series loser 3.3%, and each Wild Card Series loser 0.8% [Canadian Broadcasting Company]

Rational: I watch baseball, because I enjoy baseball.

Opportunity cost: What else could I be doing right now?

Optimization: Is the marginal utility of continuing this activity greater than the marginal utility from another activity?

Sunk Cost: I am committed to seeing this activity through to the end.

Consideration of future: Will my team make it back to the World Series in my lifetime? (I am a Mariners fan, so the "back to" is a bad assumption). Will I miss a once in a lifetime happening that I can never see live again?

Experience good: My relative enjoyment of this baseball game is partially based on my past enjoyment of baseball games.

Oligopoly: Playoff teams control more of the baseball market

Game theory: The choices of the other manager, coaches, and players are dependent on the choices of the other teams economic agents.

Other concepts: Random walk, asymmetric information, zero sum game

Common examples often involve situations where the total cost is unknowable or the desired outcome is no longer possible -- staying in a failing long term relationship, continuing to fund a failing project, standing in a long slowly-moving line. The sunk cost fallacy certainly applies.

But I think in many other popular examples where the total cost is fixed or known -- completing a degree program, finishing a marathon, watching a bad movie to the end -- it's actually a rational reframing of the remaining marginal cost by subtracting the sunk cost from the total. It's less "I should finish my degree because I'm already 3½ years in" but rather "for the marginal cost of 1 semester I can get a degree". Even when the objective has lost some luster, the much smaller marginal cost may make the decision to continue worthwhile.