Why Scam Texts About Unpaid Tolls Just Won’t Stop

Been getting scam texts about unpaid tolls? You're not alone—and there's an economic reason they're everywhere.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Have you been getting those toll road text messages lately? The ones that claim you owe a few bucks, and that your license will be suspended if you don’t pay now? You’re not alone. They’ve been flooding inboxes across the country, and they’re just believable enough to make you wonder: Did I actually miss a toll somewhere?

Even if you know better, they prey on that moment of doubt. I know I’ve taken a toll road and forgotten about it a time or two. Most of us are used to those reminders arriving by mail, not text. But doesn’t it seem like everything is coming to us on our phones instead of the mail? That tiny shift in delivery is what makes this scam so effective and so much more common.

This story isn’t just about a text message. It’s about how scammers think like economists. Specifically, how they use a concept called a separating equilibrium to filter out the people who are most likely to fall for their scheme.

But it’s also about how, thanks to automation and artificial intelligence, that filtering process is cheaper, faster, and frankly smarter than ever.

How the Scam Works

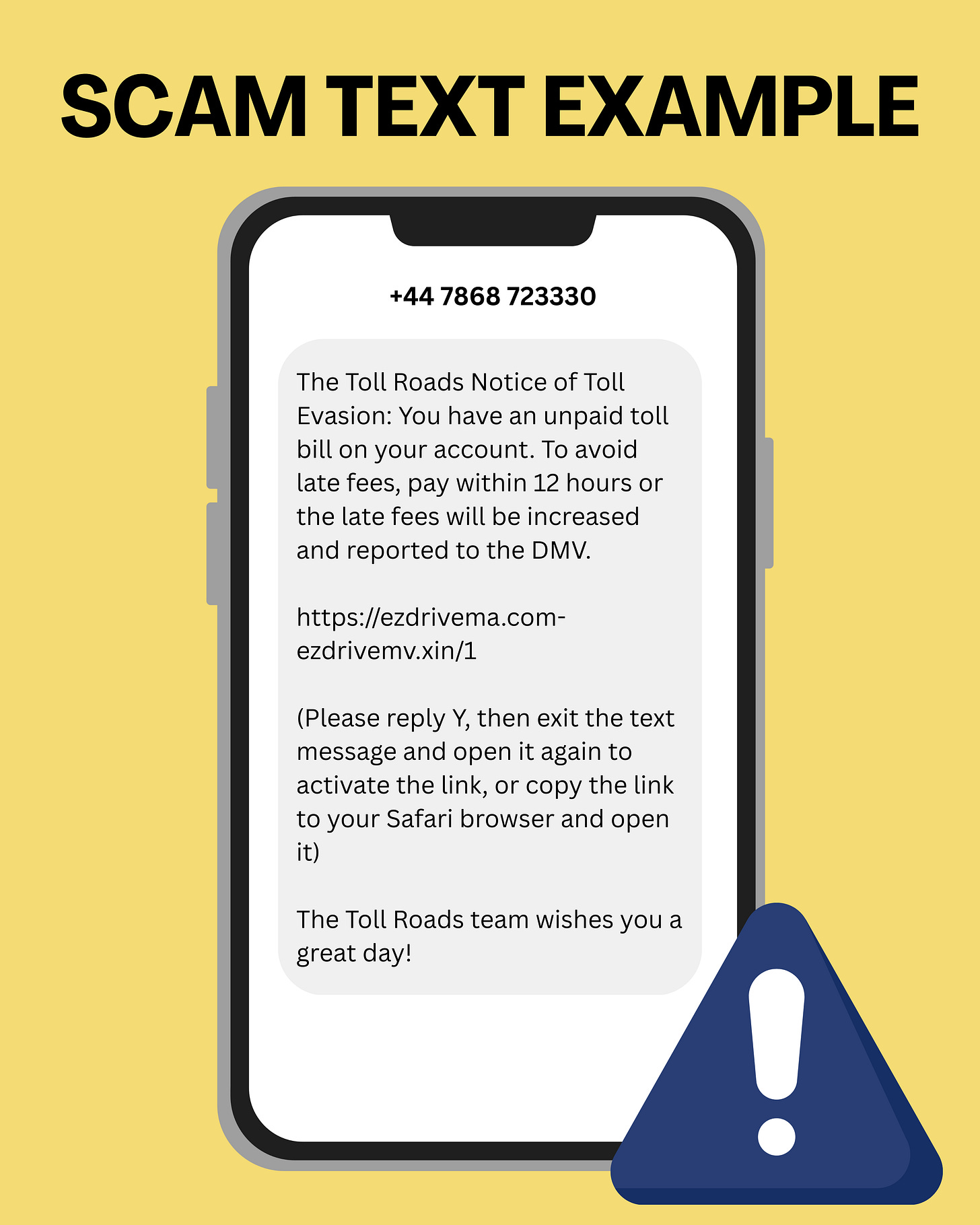

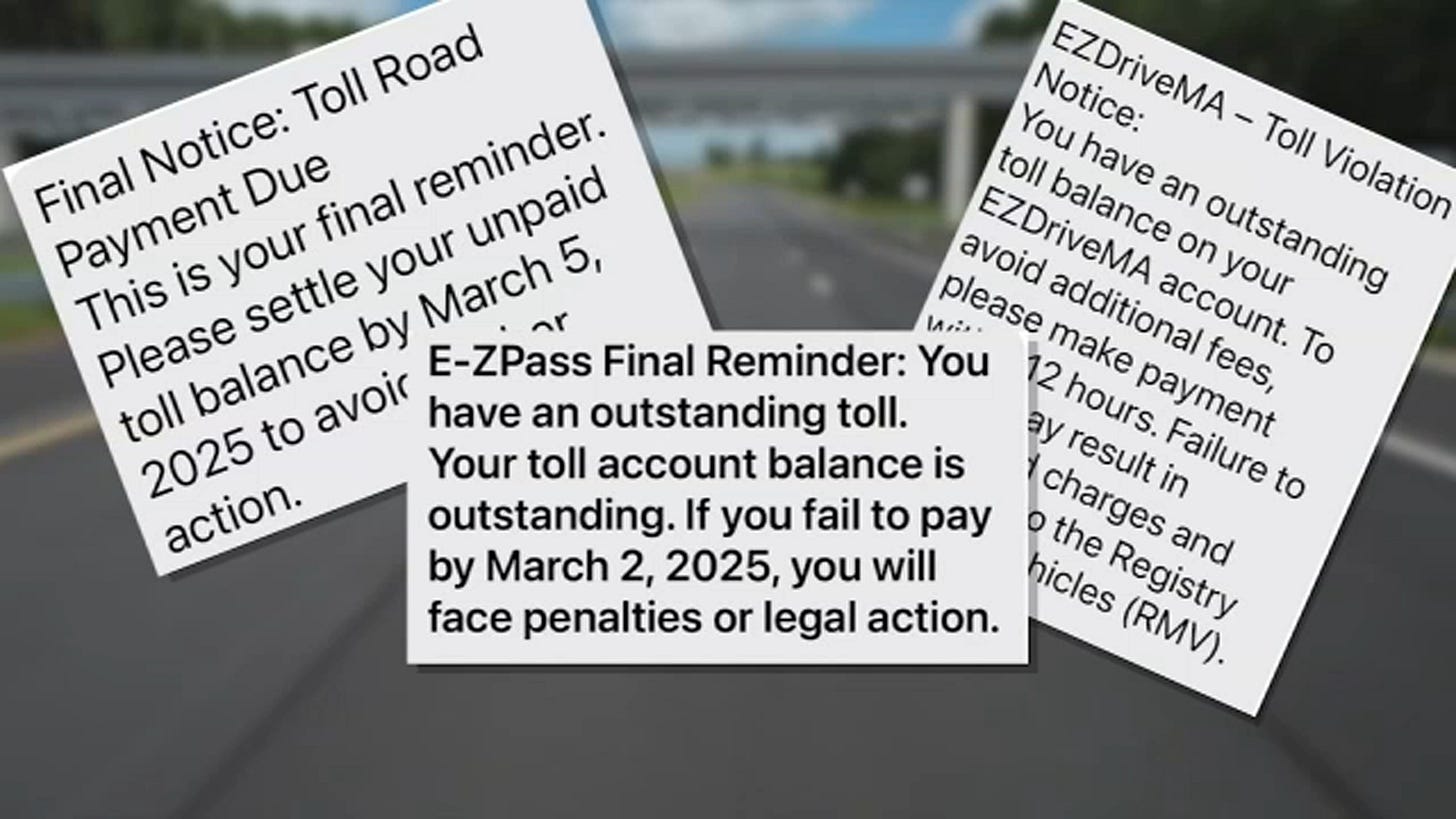

If you haven’t seen one of these messages yet, here’s the basic script: a text shows up saying you owe money for an unpaid toll. There’s a convenient link to settle up. The language is firm, a little threatening, and surprisingly official. Some even use real names like SunPass or Peach Pass, or logos lifted straight from legitimate toll agencies.

But it’s a scam. These messages don’t come from your state government. They’re sent by fraud rings, often based overseas, that have set up thousands of fake websites designed to capture your credit card info and personal details.

Some people spot the scam immediately and delete it. Others might double-check their toll account just to be sure. The script hasn’t changed, but the scale has.

Scammers can now send out millions of these messages using automated tools, text-masking software, and AI-generated language. The cost of reaching potential victims is almost zero, and that has changed the entire business model of fraud.

Remember the Nigerian Prince?

This isn’t the first time scammers have relied on human behavior to do the filtering for them. Think back to the Nigerian Prince scam. Those were the emails from a supposed royal figure offering you millions in exchange for a little help moving a fortune out of the country.

They were filled with spelling errors and wildly implausible claims. But that wasn’t carelessness. It was intentional.

Those scams were expensive to run. Once someone replied, the scammer had to invest serious time: sending emails, crafting fake documents, and even calling victims. The scammers didn’t want everyone to reply. They wanted only the most gullible to respond. If the email made you laugh or hit delete, that’s great! You filtered yourself out.

That kind of self-selection is called a separating equilibrium.

What’s a Separating Equilibrium, Anyway?

A separating equilibrium is a concept from game theory. It describes situations where people reveal something important about themselves. It’s not about what they say, but by how they behave.

In the case of the Nigerian Prince scam, responding to an obviously fake email revealed something about your vulnerability. In the case of the toll scam, clicking the link tells scammers that you’re at least uncertain enough to be worth pursuing. Skeptical people (the ones who’ve seen scams before, or who take the time to verify) filter themselves out from the pool of potential victims. They ignore the message, or they check their E-ZPass account and move on.

These scams only work if they can separate the likely victims from everyone else. Maybe they’re in a hurry. Maybe the text catches them on a day when the warning feels plausible. They click the link. And just like that, they’ve separated themselves into a group scammers want to keep engaging with.

Too few responses and the scam isn’t profitable. Too many, and banks or agencies start cracking down. That sweet spot in the middle. That’s the equilibrium.

Automation Is Changing the Game

Here’s where things have shifted since the Nigerian Prince last contacted you. In the past, fraudsters needed to scare away the skeptics because every follow-up was labor-intensive. But with artificial intelligence and automation, the marginal cost of each new target has dropped to almost zero.

A scammer doesn’t need to convince you with a long con. They just need a few clicks. And if the message looks realistic enough, or if it arrives when you’re distracted or busy, that’s often all it takes.

The scam doesn’t have to be as absurd anymore. It can afford to be plausible. Instead of filtering for the truly gullible, scammers can now target anyone who’s not paying close attention. The separating equilibrium still exists, but it’s gotten broader because the cost of being wrong is lower.

Final Thoughts

If you’ve clicked one of those toll scam links, don’t panic. But don’t ignore it, either. Report the scam to the Federal Trade Commission.

And if you haven’t clicked one, now you know why you’re still getting the texts. They’re not targeting you specifically. You’re just part of a wide net made possible by cheaper tools and faster tech.

Scammers aren’t the only ones using separating equilibria to filter people. The same idea shows up in lots of places where someone needs to screen a large group and only focus on a specific subset.

Job applications with long, clunky portals? Sometimes the point isn’t just to gather information, but rather to see who’s willing to finish. Awkward college essay topics beyond the Common App? Annoying, yes. But they also filter for persistence and attention to detail.

In each case, the system is asking a question: Are you the kind of person we’re looking for? The answer isn’t always obvious. But now you know what to look for.

A cybersecurity report has found that cybercriminals have registered more than 10,000 domains for a scam about unpaid toll bills [WGAU Radio]

The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center received more than 60,000 complaints in 2024 reporting the unpaid toll scam [CNBC]

‘Nigerian prince’ email scams still rake in over $700,000 a year [CNBC]

There are more than 6,546.74 miles of toll roads across the United States [U.S. Federal Highway Administration]

Americans made 5 billion tolled trips in 2011 [International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association]

Thank god for open comments sections

Because we've been trying to reach you about your vehicle's extended warranty

Thanks Jadrian. Good stuff. AI will on balance make our lives better imo, but this is the other side of the coin.