What to Know About the Federal Reserve’s Structure Amid Talk of Change

An explainer on the Federal Reserve’s unique structure—and why certain changes are "not permitted under the law"

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 5,700 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

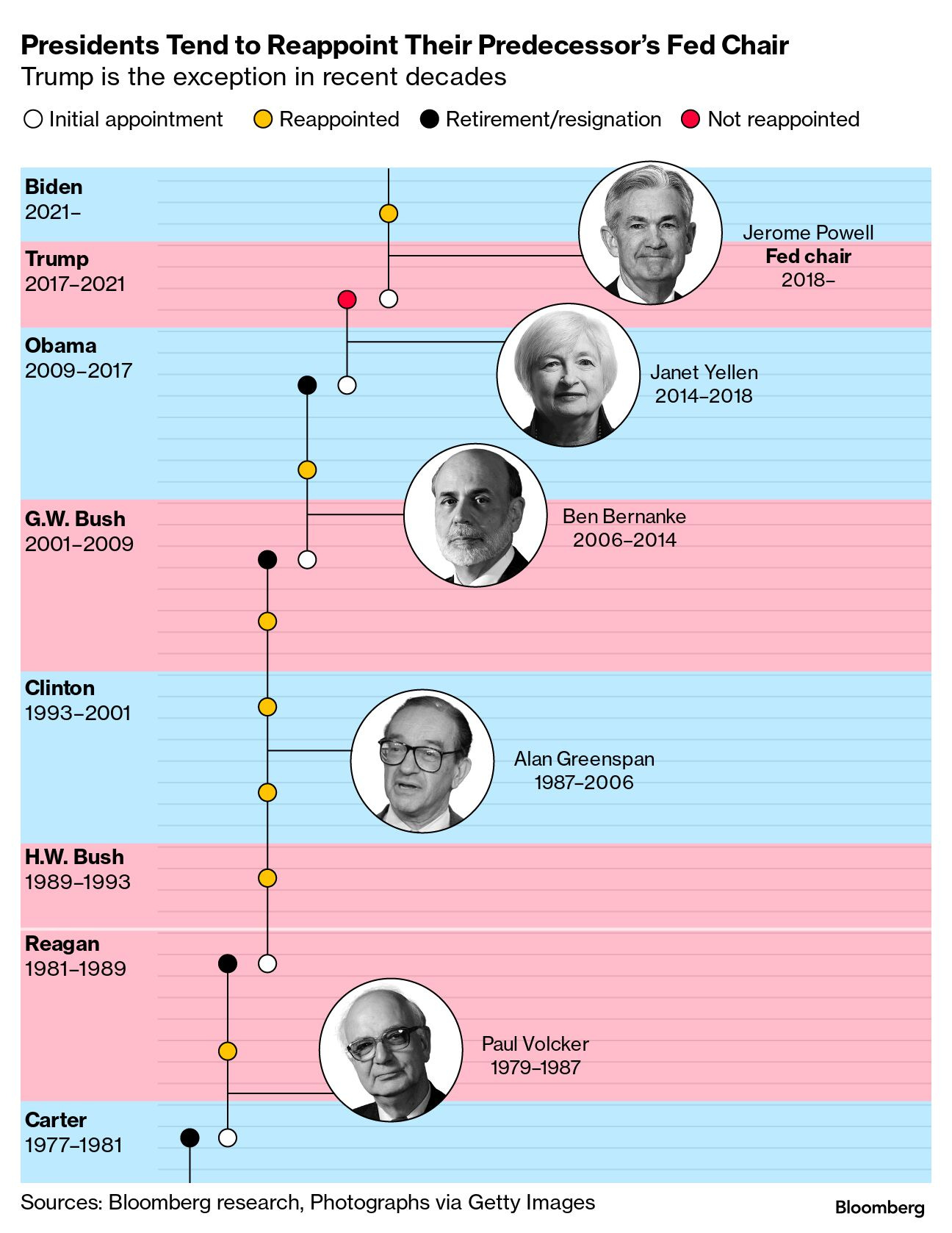

With a new administration on the horizon, rumors are swirling about potential shakeups in Washington—and the Federal Reserve has been on the list. But when asked whether President-elect Donald Trump could replace him, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell responded with a direct response: the President doesn’t have the authority. His comment revealed a larger truth—most Americans don’t fully understand what the Federal Reserve is or how it works.

The Federal Reserve (known as “the Fed”) is indeed the central bank of the United States, but it’s built in a unique way. Many people know the Fed as the agency that influences interest rates and inflation, but the Fed is much more complex than that. It was structured to mix local and national perspectives, public oversight, and policy consistency. Let’s unpack what this means by looking at the Fed’s structure and purpose—from the roles of its governing bodies to the powers (and limits) of its Chair.

The Structure of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve was created in 1913 through the Federal Reserve Act. Its purpose was to create a financial system that would be more stable. But designing a central bank that would work for such a large and diverse country wasn’t straightforward. Lawmakers struck a careful balance between national control and regional influence, establishing a structure that includes public oversight, local input, and some degree of autonomy.

The Fed operates with three key components that each serve a specific purpose in the pursuit of effective monetary policy: the Board of Governors, twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Together, they form the core of the Fed’s system for managing the U.S. economy.

The Board of Governors is based in Washington, D.C., and serves as the Fed’s central oversight body. Comprising seven members appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, this board is responsible for guiding important decisions about the country’s monetary policy and regulating financial institutions. Board members serve staggered 14-year terms, which provides a level of continuity and insulates them from political pressures that might otherwise sway short-term decisions.

While the Board of Governors oversees the system as a whole, the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks serve as the Fed’s local representatives across the country. Each bank operates within a specific geographic area, which allows it to keep an eye on local economic conditions and financial concerns unique to its region. These banks bring vital perspectives on everything from agricultural economies in the Midwest to tech-driven growth on the West Coast. These banks operate semi-independently within the Fed’s framework but are tasked with carrying out policies established in Washington.

Finally, there’s the Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC. This is where the Fed’s major policy decisions happen. The FOMC includes all seven members of the Board of Governors and five regional bank presidents, who rotate positions each year except the New York bank. This committee meets regularly to decide the direction of U.S. monetary policy, most recently with high regard for interest rates. By setting the federal funds rate, the FOMC indirectly influences everything from the cost of business loans to the dollar’s strength on the global market. The committee considers national and regional data to make choices aimed at keeping inflation low and promoting employment.

This layered structure—with the Board of Governors at the center, regional banks feeding in local insights, and the FOMC coordinating policy decisions—allows the Fed to balance national priorities with regional perspectives. It’s a design that enables the Fed to stay responsive, informed, and consistent.

The Role of the Board of Governors and the Importance of the Chair

The Chair of the Federal Reserve stands as the institution’s most influential figure. The position is appointed by the President, confirmed by the Senate, and comes with a renewable four-year term. But unlike other high-profile government officials, the Fed Chair isn’t simply a political appointee. They’re tasked with steering the U.S. economy through some of its most complex challenges, often making decisions that impact every American’s financial life.

When the Chair speaks, the world listens—and reacts. Financial markets hang on the Chair’s every word, as even subtle shifts in tone can reveal the Fed’s outlook on economic growth, inflation, and interest rates. When the Chair hints at a potential rate hike, for instance, it could mean higher costs for loans, mortgages, and credit cards, affecting household budgets and business decisions across the country. Conversely, if the Chair signals a rate cut, markets may react by rallying, as lower interest rates generally encourage borrowing and spending.

Yet, the Chair is more than just the voice of the Fed. They play a critical role in setting the agenda for both the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), often guiding the timing and nature of major policy shifts. While the four-year term provides an opportunity for new administrations to have input in leadership, the Chair operates independently of the President’s directives, focusing on the Fed’s dual mandate: maintaining stable prices and maximizing employment.

This independence allows the Chair to make hard choices—even unpopular ones—that are intended to keep the economy steady over time, rather than responding to short-term political pressures. In this way, the Fed Chair occupies a unique and complex role, balancing immediate financial impacts with long-term economic stability.

Fed Appointments Are Designed for Stability, Not Politics

The long terms of Fed members aren’t simply bureaucratic tradition; they’re a deliberate safeguard for the Fed’s independence. Appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, Board members serve staggered 14-year terms. These are intended to last far beyond any single administration. This arrangement incentivizes the Fed to make decisions that are driven by long-term economic needs.

The Chair also operates with built-in insulation from the President’s influence. The Chair’s term is purposely staggered, meaning it doesn’t align with the President’s. This was done so that any single administration had only limited sway over Fed leadership. What’s more, this isn’t a role subject to the President’s whim: the Federal Reserve Act specifies that Board members, including the Chair, can only be removed “for cause.” Traditionally, “cause” has been understood to mean serious misconduct or neglect, not policy disagreements. In other words, the President can’t replace a Fed Chair simply over disputes about interest rates or economic philosophy.

Why Politics Must Stay Out of Monetary Policy

When it comes to economic policy, few institutions affect the lives of Americans as profoundly as the Federal Reserve. This central bank, often referred to simply as “the Fed,” plays a critical role in steering the U.S. economy—yet it typically operates behind closed doors, away from the watchful eyes of Congress and the President.

Final Thoughts

Calls for more oversight of the Federal Reserve have grown in recent years, with critics arguing that an unelected body wielding such influence should be more accountable to elected officials. Yet the Fed’s independence is precisely what allows it to make tough decisions that keep the economy stable, even when those choices are unpopular.

The Fed is tasked with promoting stable prices and maximum employment—objectives that require the willingness to make difficult calls, whether by raising rates to combat inflation or lowering them to stimulate growth. If the Fed were swayed by the same political pressures facing other agencies, it might hesitate to make these hard choices.

Jerome Powell’s recent comments are a striking reminder of the Fed’s unique role and structure in the federal government. This system wasn’t designed to reject accountability but to ensure that monetary policy remains insulated from shifting political tides. At a time of rapid change, the Fed’s stability has become more important than ever.

In 2022, only 49% of Americans believed that the Federal Reserve makes decisions that are in the best interests of the average American [Axios/Ipsos Poll]

The vault at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York holds approximately 507,000 gold bars, with a combined weight of 6,331 metric tons [Federal Reserve Bank of New York]

The Federal Reserve holds $4.34 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities [Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System | FRED]

The Fed operates the Fedwire Funds Service, a real-time payments system that processes over $4 trillion per day in payments [Liberty Street Economics]

The Fed doesn’t print money itself but has ordered between 4.1 billion and 5.9 billion notes from the U.S. Treasury’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing for 2025, with a total value ranging from $83.2 billion to $113.0 billion [Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System]

I had to be reminded that the Fed Chairman is not a Presidential appointee. Or that he can’t be easily replaced by the President-elect. Some stability would be nice.