What Amazon Prime Day Can Teach Us About Economics

A look at why Amazon's deep discounts are actually a high-priced strategy

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Amazon Prime Day kicks off this week, and Prime members have already been getting “exclusive early access” emails and “lightning deal” alerts. Since launching in 2015, Prime Day has become one of the biggest online shopping events of the year, right alongside Black Friday. From July 8 to 11 this year, millions of shoppers will race to snag time-limited deals at shockingly low prices.

It may look like Amazon is losing out on a lot of potential profit, but its decisions are textbook strategies that economists refer to as price discrimination. Today’s post isn’t going to talk about whether consumers are feeling confident or spending more this summer. Those are valid concerns for many across the country, but today’s post will instead lay out how one of the most profitable companies in the world gets consumers to pay before they ever purchase a product.

What Is Amazon Prime (and Prime Day)?

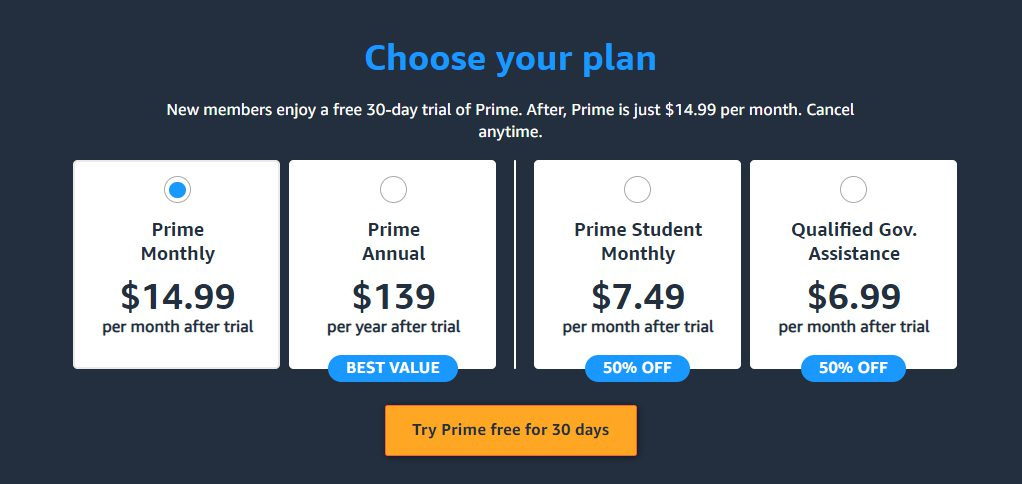

Most people know what Amazon Prime is, even if they aren’t one of Amazon’s 220 million global members. It’s the company’s all-in-one subscription program that offers complimentary two-day shipping, streaming video, and a growing list of perks in exchange for a monthly or annual fee.

Prime Day is Amazon’s version of a doorbuster sale, but with a twist: you need to pay the cover charge to get in. The annual event spans multiple days and features steep, time-limited discounts on everything from laptops to laundry detergent. Anyone can shop on Amazon during Prime Day, but the best deals are reserved for Prime members.

The event serves two purposes for the world’s fourth-largest company. Its customers can grab deep discounts, especially on big-ticket items they may have been eyeing for weeks. For Amazon, it’s part marketing campaign, part revenue stream, and part loyalty test. Prime Day strengthens the case for paying to be a Prime member in the first place.

What Economists Mean by “Price Discrimination”

The word “discrimination” usually brings to mind something harmful, usually related to the treatment of someone based on their race or gender. To an economist, price discrimination simply means charging different prices to unique groups of customers for the same product or service.

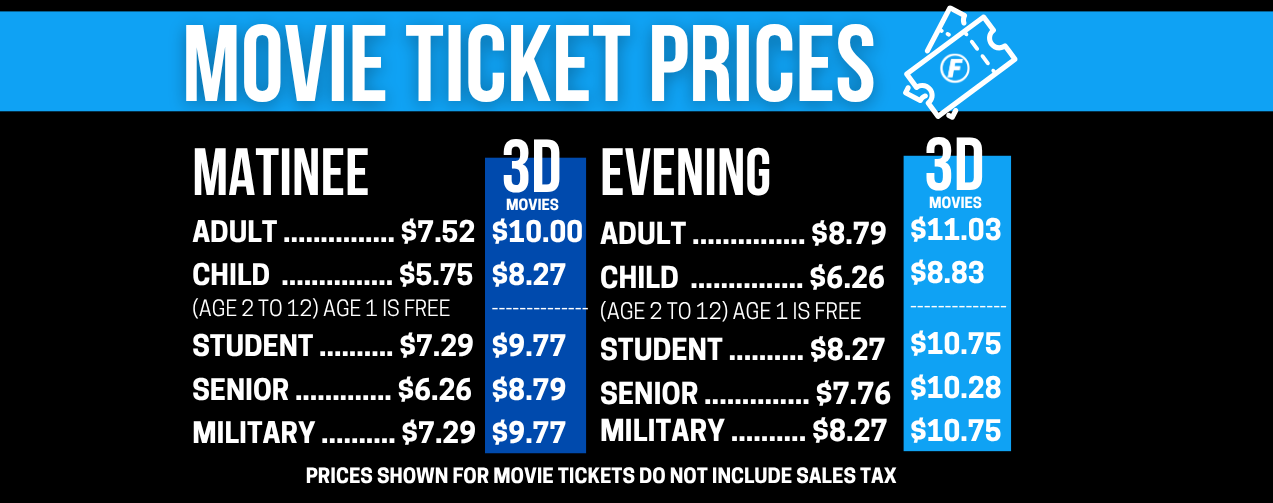

The company’s goal is to increase profits by charging a price that is closer to what the customer is willing to pay. This tactic happens all the time, in a variety of ways! Airlines charge more for the same seat depending on when you book the ticket, and movie theaters offer student and senior discounts to account for income differences. Neither of these reflects anything about the customer’s skin color or gender. The decisions are based on the typical willingness to pay for each group.

Not all price discrimination tactics target groups in the same way. Economists often place the different strategies into one of three buckets. In first-degree price discrimination, a company tries to charge each customer exactly what they’re willing to pay for the product. That’s incredibly hard to do in real life, but companies are getting better at it thanks to how much data they can collect on us.

In third-degree price discrimination, the price changes for easily identifiable groups. This would be like offering discounts to students, seniors, or veterans. It’s perhaps the most common strategy you’ll see around your own town. Amazon even offers a discounted Prime membership called Prime for Young Adults for individuals aged 18 to 24.

But what about events like Prime Day? This strategy falls under second-degree price discrimination, where customers sort themselves into different groups based on how much they’re willing to pay. The company only knows who belongs in each group after they’ve purchased the product. It’s the same classification that Amazon uses to figure out which customers are willing to commit to an annual plan instead of a monthly plan.

How Amazon Gets You to Pay to Save

With second-degree price discrimination, companies can’t easily identify you before you purchase the product. Instead, customers face a menu of options for each group, and then customers sort themselves into groups based on how much they’re willing to pay.

That could include tactics like year-long subscriptions or bulk discounts, but another common example of this strategy is something called a two-part tariff: a pricing model with two components:

An access fee just to get in the door.

A per-unit price for the goods or services you actually use.

A Prime membership represents the access fee to participate in the deals offered during Prime Day. Of course, there are also shipping benefits and access to other Amazon services (e.g., music, video, etc.). But the low prices on Amazon Prime Day are the second part of the requirement for two-part tariffs: discounted prices that only members can access.

The fixed fee ensures a steady stream of revenue from customers, even if they don’t take advantage of Prime Day deals. But for many Prime members, the discounts and services encourage customers to spend more, more often. Amazon would love to be able to easily identify these customers to push more ads toward them, but Amazon doesn’t have to guess who’s price-sensitive and who isn’t because their customers self-select into the groups.

It’s this last condition that makes second-degree price discrimination so powerful. It doesn’t require invasive data collection or awkward identification strategies. They don’t have to check any IDs or worry about someone lying about their age. Second-degree price discrimination lets customers reveal their preferences by opting into the group that fits their preferences.

Final Thoughts

You’ve probably encountered two-part tariffs before without even realizing it. Wholesale clubs like Costco and Sam’s Club also charge you a membership fee, then offer lower prices once you’re inside. Subscription platforms like Xbox Game Pass charge a flat fee for the box and then charge you for each game you want to play.

The idea is always the same: separate the right to buy from the price you pay for the product. That lets companies better identify how much different groups of customers are willing to spend and, in turn, profit more than they would if they charged a single price to everyone.

If you want a fun explainer of this idea in a completely different context, check out my friend Matt Hill’s experience trying to sell economics graphs on OnlyFans. (Note: there’s nothing inappropriate in the video itself, but maybe don’t click on it while you’re at work or school.)

For those of you looking to make the most of your Prime membership this week, consider tossing a few books in your cart. I recently updated my Bookshop shelf with reading recommendations for teachers, students, and the econ-curious. If you’d rather not support Amazon directly, Bookshop is a great alternative that supports independent bookstores.

If you want a brief summary of my favorite books from the past few years, check out the articles I wrote for 2022, 2023, and 2024. If you need a last-minute beach read this summer, you can always pick up a copy of my favorite book on economics. I personally think it’s one of the most engaging introductions to economics out there. I could be a little biased, though.

If you found this explainer insightful, consider sharing it with someone who has an Amazon Prime account. Hopefully, they’ll buy you a book as a thank you gift. If you’re new here, subscribe to get more practical economics lessons like this one, drawn from headlines and everyday life. No jargon. No lectures. Just useful ideas, delivered weekly.

Consumer confidence deteriorated by 5.4 points in June, erasing almost half of May’s sharp gains [The Conference Board]

Amazon launched its Prime subscription in February of 2005 at the initial price point of $79 a year [Pattern]

Today, Amazon customers in the U.S. pay $140 a year (or $15 per month) for a Prime subscription [Yahoo! Finance]

During last year’s event, online shoppers spent a record-setting $14.2 billion, up 11% from 2023 [USA Today]

Analysts at Bank of America believe the 2025 Prime Day event could bring in $21.4 billion in gross merchandise value [Morningstar]