What Your Venmo Behavior Says About You

Do you round up or send the exact amount? That tiny decision reveals more about your brain, and your social habits, than you might think.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Imagine this: You’re out grabbing coffee with a few friends. One person offers to pay for the group. It’s a small act of generosity. You thank them, promise to pay them back later, and carry on with your day.

Then, a couple of hours later, the text comes through:

“Hey! Your coffee was $7.58. Just Venmo me when you get a chance :)”

And now… the moment of truth. How much do you actually send?

This is one of those tiny, modern dilemmas we’ve all faced. It’s small stakes, but surprisingly loaded. Do you round up as a thank-you, or do you send the exact amount, because that’s what’s owed?

It’s a simple choice on the surface. But your answer might reveal something deeper about how you think about fairness, friendship, and what economists call mental accounting.

This Isn’t Just About Coffee

Twenty years ago, you probably would’ve paid your friend back in cash. You likely rounded up to avoid handing them loose change. If the total was $7.58, you’d give them eight dollars and tell them to keep the change.

But today? Venmo, Cash App, and Zelle make it easy to send precise amounts. No quarters, no dimes. Just clean digital transfers. And yet… it still feels complicated.

When I ran this poll on social media, the responses were split. About half said they’d send exactly $7.58. The other half rounded up to $8.

So what’s going on here?

Etiquette writers tend to encourage rounding up. They say to treat it like a tip. After all, your friend fronted the bill, possibly chased people down, and maybe even did the mental math to split it fairly. Tossing in an extra 42 cents is a small way to say thanks.

But that advice raises a deeper question: What would an economist do? We’ll get there. But first, let’s talk about what’s actually happening inside our heads.

Mental Accounting, Meet Venmo

Here’s where the economics gets interesting. Even though $7.58 is an easily transferable number, our brains don’t treat it that way. We categorize it. We tell ourselves things like:

“It’s just coffee, I’ll round up.”

“It was $7-something, close enough.”

“They covered the bill, I’ll send a little extra.”

This is what behavioral economists call mental accounting, a concept developed by Richard Thaler, who would eventually win a Nobel Prize for showing how people think about money in irrational ways. Mental accounting happens when we treat the same amount of money differently depending on how we label it in our minds.

Most of us would happily round up the 42 cents at a coffee shop as a tip. But reimbursing a friend? That same 42 cents suddenly becomes a choice about generosity or social expectations. Some people will round up to show appreciation. But some, let’s call them economic purists, send exactly $7.58 because that’s what they were told they owed.

There’s no right answer, but every option does send a message. Even when apps make it easy to be precise, our brains still reach for rules of thumb. Unfortunately, those rules aren’t always rational.

What Would an Economist Do?

Ask an economist how much you should send, and they’ll probably give you the classic response: “Well… it depends.” (This is why President Truman famously said he wanted a one-armed economist.)

In this situation, it really does depend on whether you prioritize economic precision or social harmony. If you’re the type who tries to live like homo economicus, the rational agent from Econ 101, you send exactly $7.58. Why? Probably because of the fungibility of money.

Fungibility means one dollar is perfectly interchangeable with any other dollar. That extra 42 cents could be used on groceries, rent, or tomorrow’s coffee. Overpaying by even a little is a form of misallocated resources.

But most of us aren’t calculators. We’re people. And people care about more than just cents and ledgers. We care about the social meaning behind tiny choices.

Exact payment could come across as fair… or cold. Rounding up becomes a gesture of thanks. Even economists know that money isn’t always treated like money. It’s soaked in context.

Final Thoughts

The truth is, we could avoid all this awkwardness by just talking about money more. But we don’t. We don’t ask if our friend prefers rounding up or down. We don’t set expectations for casual repayments. We just hope we’re reading the vibe correctly.

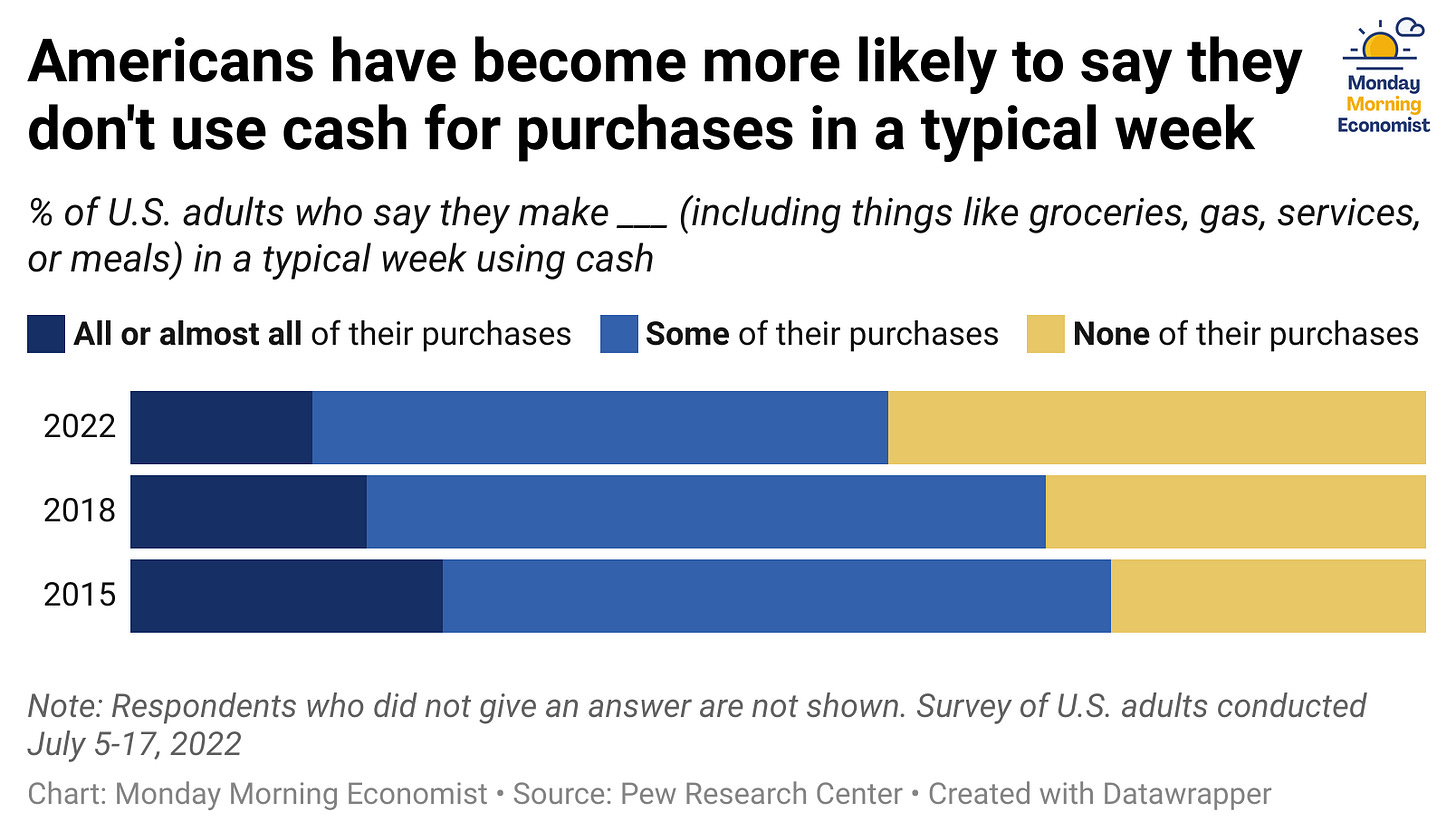

A few decades ago, we were also more likely to skip the repayment process entirely in favor of informal exchanges. Your friend gets the coffee this week, and you’ll pick it up next week. But digital payment apps like Venmo have changed all that. Now we settle debts instantly (and visibly). That shift has made the etiquette feel murkier.

Check out this summary from Hanna Horvath of Your Brain on Money on how digital payments have changed social dynamics:

So instead of talking about money, we guess. We round. We overthink. We under-explain. And that tiny $7.58 transaction becomes a surprisingly personal moment. The economist in me wants to tell you to just ask the other person what they prefer. But the human in me knows: Most people won’t ask.

So the next time you go to Venmo someone back, don’t just think about the number. Think about the story you’re telling with it. Because odds are, you’re not just sending $7.58.

If you enjoyed this post, don’t just keep it to yourself. Send it to the last person who Venmoed you the exact amount. You know the one. Or better yet… the next time someone repays you on the dot, reply with this article and say: “An economist has thoughts.”

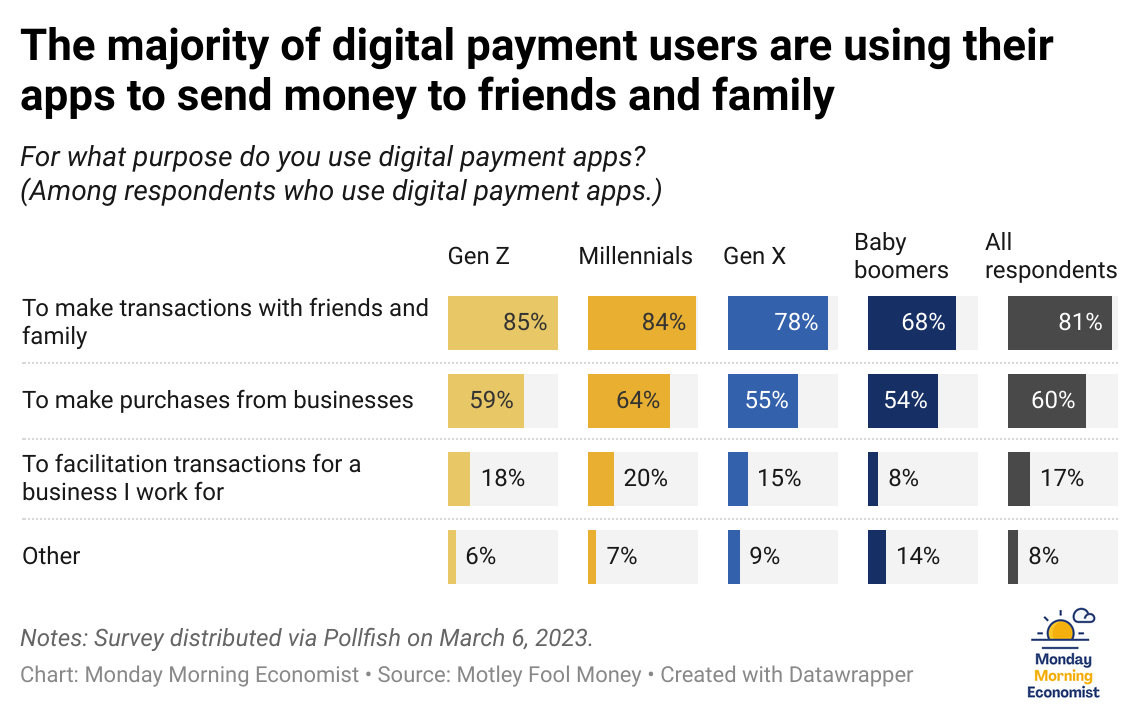

A survey of 1,000 American consumers finds nearly half (47%) of U.S. adults who use payment apps to split bills for restaurant meals, groceries, and other regular purchases [Forbes Advisor]

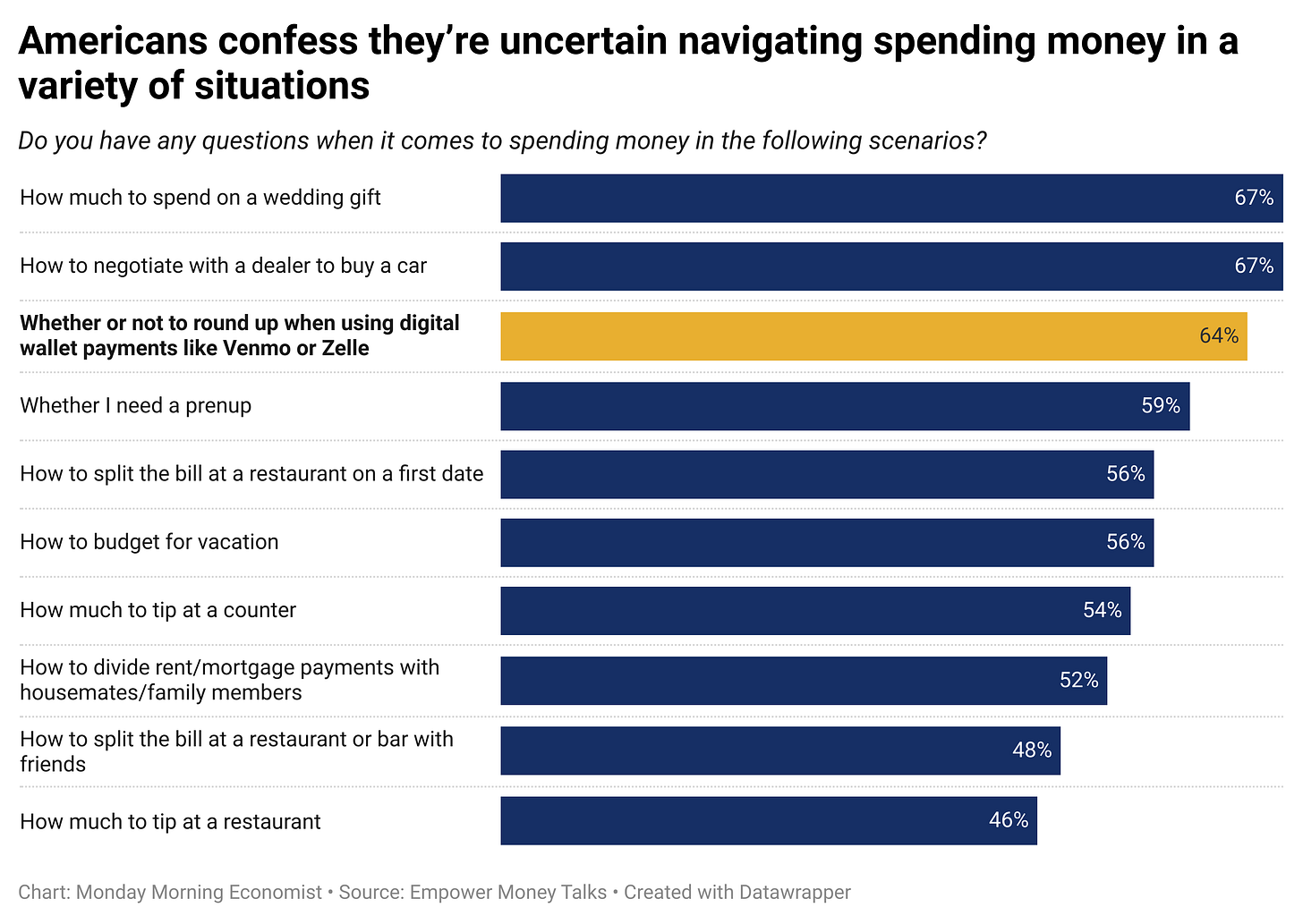

In a different survey, 64% of respondents weren’t sure whether or not to round up to the nearest dollar when repaying a person via Venmo (or Zelle) [Empower]

Professor Thaler made a cameo appearance in the movie "The Big Short" to explain the "hot hand fallacy" as it applied to synthetic collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) during the housing bubble before the 2007-2008 financial crisis [IMDB]

In a survey of its readers, 55% of respondents said that you don’t need to Venmo a friend if you owe them less than $5, and 85% of people don’t expect their friends to pay them back for items less than $5 [PopSugar]

My venmo is only used when i rarely go get a Man E cure (their spelling ) and i leave a tip. Im sure there is some insight there but mow much. Great article like always!

So I am an economist by training, in my early 40s. My first instinct is to send the exact amount. That said, if a friend offers to pay for coffee, I would indeed make a mental note to get it next time. I guess if one person paid for the whole group out of convenience, and then instructs each person bilaterally how much is owed, then the exact amount or rounding up are both acceptable. I would definitely not round down.