Taking A Bite Out of the Competition

What a crustless PB&J lawsuit reveals about competition and the power of looking different.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

The NFL goes through about 80,000 Uncrustables every season.

Professional football players who weigh 250 pounds and sprint forty yards in under five seconds eat the same frozen peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches found in kids’ lunchboxes arond the country.

Now, the company behind those sandwiches is suing Trader Joe’s. Not for stealing the recipe, but for copying the shape and the color scheme.

Smucker says Trader Joe’s new crustless PB&J sandwiches look too much like Uncrustables: same round design, same crimped edges, even the same photo of a bitten sandwich on the box. Trader Joe’s hasn’t commented, but this is familiar territory. The company has built a business on dupes: look-alike versions of popular products that often taste the same but cost a lot less.

Which raises a question only an economist could love: How can two sandwiches made of the same bread, peanut butter, and jelly be so different that one of them is worth suing over?

A Dupe Too Far

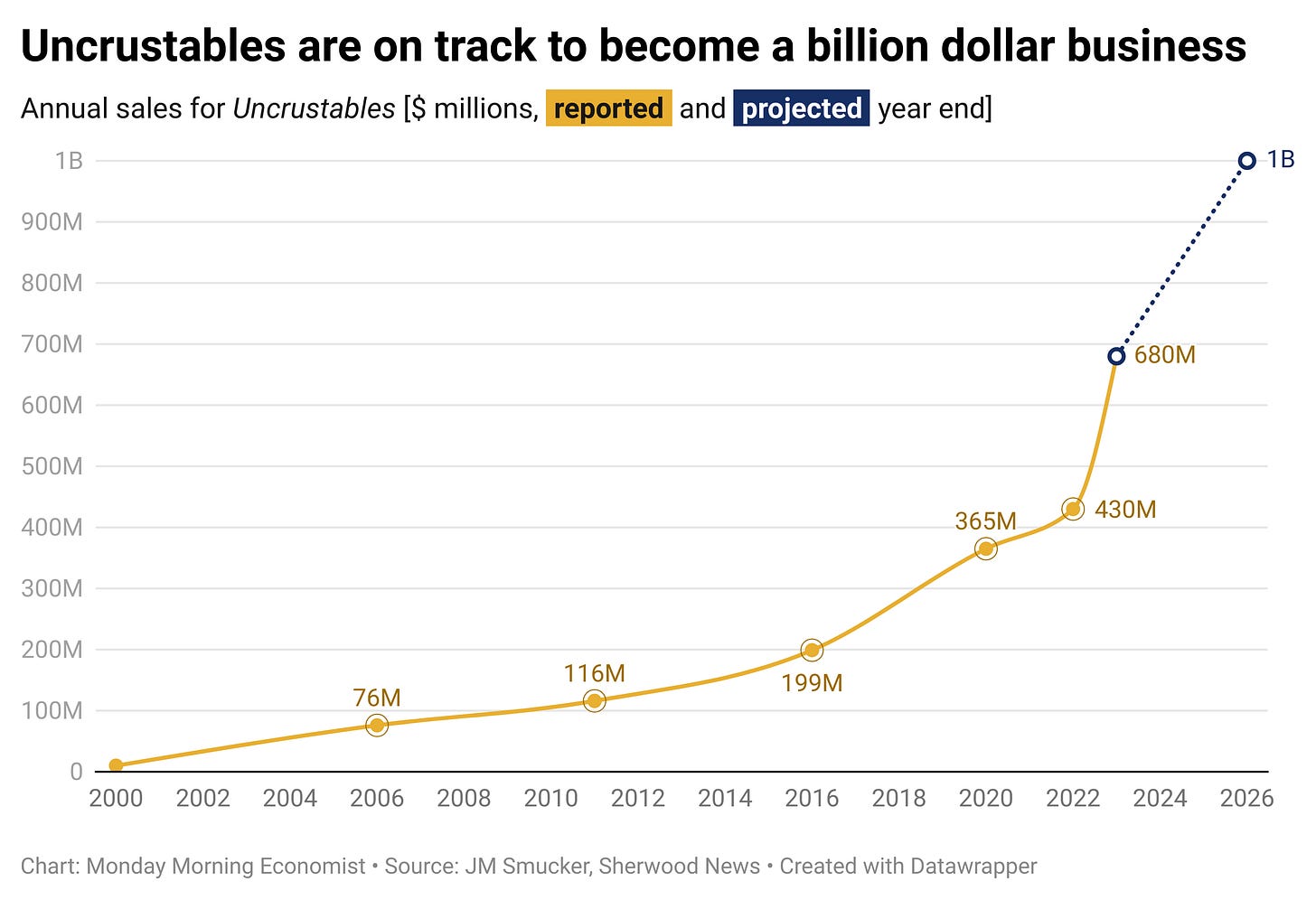

The lawsuit was filed in federal court in Ohio, where Smucker’s is based. It claims Trader Joe’s frozen “Crustless Peanut Butter & Strawberry Jam Sandwiches” are obvious copycats of Uncrustables, the circular, crimped-edge sandwiches that is on track to become a billion-dollar brand.

Smucker’s argument isn’t that Trader Joe’s can’t sell peanut butter and jelly. The company says it doesn’t mind competition. What it does mind is when that competition looks too much like its own.

According to the complaint, Trader Joe’s packaging confuses consumers and “trades off Smucker’s valuable goodwill.” Trader Joe’s hasn’t responded yet, but legal experts think its defense will be straightforward: customers know when they’re buying something from Trader Joe’s. The store’s private-label “dupe” strategy is part of its appeal. Oreos become “Joe-Joe’s,” Cheerios become “O’s,” and so on.

That’s part of the tension here. Grocery shelves are full of near-perfect substitutes. Competing on price alone is dangerous. Most store-brand products are cheaper versions of whatever sits beside them, designed to look familiar enough that shoppers reach for them but not so identical that lawyers get involved.

Smucker’s says this one crosses the line.

The Grocery Game

The grocery industry is one of the most competitive markets in the economy. Profit margins are razor-thin, often just a few cents on each dollar of sales. When products are nearly identical, stores compete on price, and prices eventually fall until there’s little profit left to earn.

Economists call this perfect competition. In a perfectly competitive market, products are indistinguishable, and firms are “price takers.” They can’t raise prices without losing customers because buyers can always find the same product for less somewhere else.

If frozen, crustless peanut butter and jelly sandwiches were perfectly competitive, each company’s demand curve would be perfectly flat. No matter how much a firm spends on advertising or packaging, it couldn’t convince consumers to pay more than the going rate. Prices would drop until each firm earned just enough to cover its costs.

That eventual outcome (zero economic profit) is exactly the world Smucker’s wants to avoid. And that’s where the lawyers come in.

Standing Out in a Sea of Sameness

Most real-world markets aren’t perfectly competitive. They’re monopolistically competitive, meaning firms sell similar products that are just different enough to matter.

That’s where product differentiation comes in. It’s a way of making a product stand out in consumers’ minds, even if it isn’t that different in reality. Sometimes it’s functional, like a better seal or longer shelf life. Sometimes it’s emotional, like a brand parents trust.

Uncrustables are a great example. They’re not the only frozen PB&J, but they’re the most recognizable. Smucker’s claims to have spent more than $1 billion developing the product, perfecting the packaging, and marketing the brand. The payoff is a loyal customer base that includes parents, firefighters, and even professional athletes.

That kind of differentiation gives Smucker’s a small amount of market power. That means Smucker’s can raise prices slightly without losing all its customers because people see Uncrustables as something special.

But in monopolistic competition, those profits don’t last forever. When a firm earns short-run profits, new competitors enter the market (like Trader Joe’s) and the extra profits are competed away. In the long run, even monopolistically competitive firms earn zero economic profit, just like in perfect competition.

If they want to keep earning economic profit, companies have to keep differentiating. They release new versions, adjust flavors, or rebrand to hold consumer attention. Smucker’s has already expanded beyond the traditional PB&J with seasonal fillings and protein-packed versions. Advertising and innovation are what keep its sandwiches, and its profits, from blending into the crowd.

Final Thoughts

And that’s what this lawsuit is really about. Smucker’s can’t stop other companies from selling crustless PB&Js, and it says as much. What it wants is for Trader Joe’s to change the design and packaging enough that consumers can tell the difference.

If Trader Joe’s version looks identical, it becomes a perfect substitute. And when products are perfect substitutes, profits disappear. Smucker’s isn’t just protecting a sandwich. It’s protecting the idea that its sandwich is different.

It’s really easy to focus on price when talking about competition, but firms compete just as much on perceptions. The Uncrustables lawsuit might sound silly, but it’s a reminder of how much effort companies put into standing out in crowded markets. Differentiation turns plain white bread into something special.

If you enjoyed this story, share it with a friend who still cuts the crusts off their sandwiches. And if you like learning the economics behind everyday life, subscribe to get new posts every Monday morning.

U.S. Patent No. 6,004,596, titled “Sealed Crustless Sandwich,” was issued to inventors Len Kretchman and David Geske on December 21, 1999, but was later invalidated in 2006 for obviousness and prior use [The Wall Street Journal]

The number of Uncrustables eaten by NFL players in one season would stretch more than 18 yards across a football field [The New York Times]

Trader Joe’s sells its four-pack of crustless PB&J sandwiches for $3.79; the same pack of Uncrustables goes for $4.79 at retailers like Target [ABC News]

Grocery stores typically operate on profit margins of just 1% to 3% [Marketplace]

There are three U.S. bakeries that specialize exclusively in producing Uncrustables [J.M. Smucker]

"I'm going to bring to bear the power of the state against nonviolent people for copying an idea which is infinitely reproducible" is rent seeking at its finest, and it makes society worse off

No one wants to be in a market where they compete on price. Great example of protecting a brand.