The Billions We Forget We're Owed

In theory, you’d know if someone owed you money. In practice, you probably don’t.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

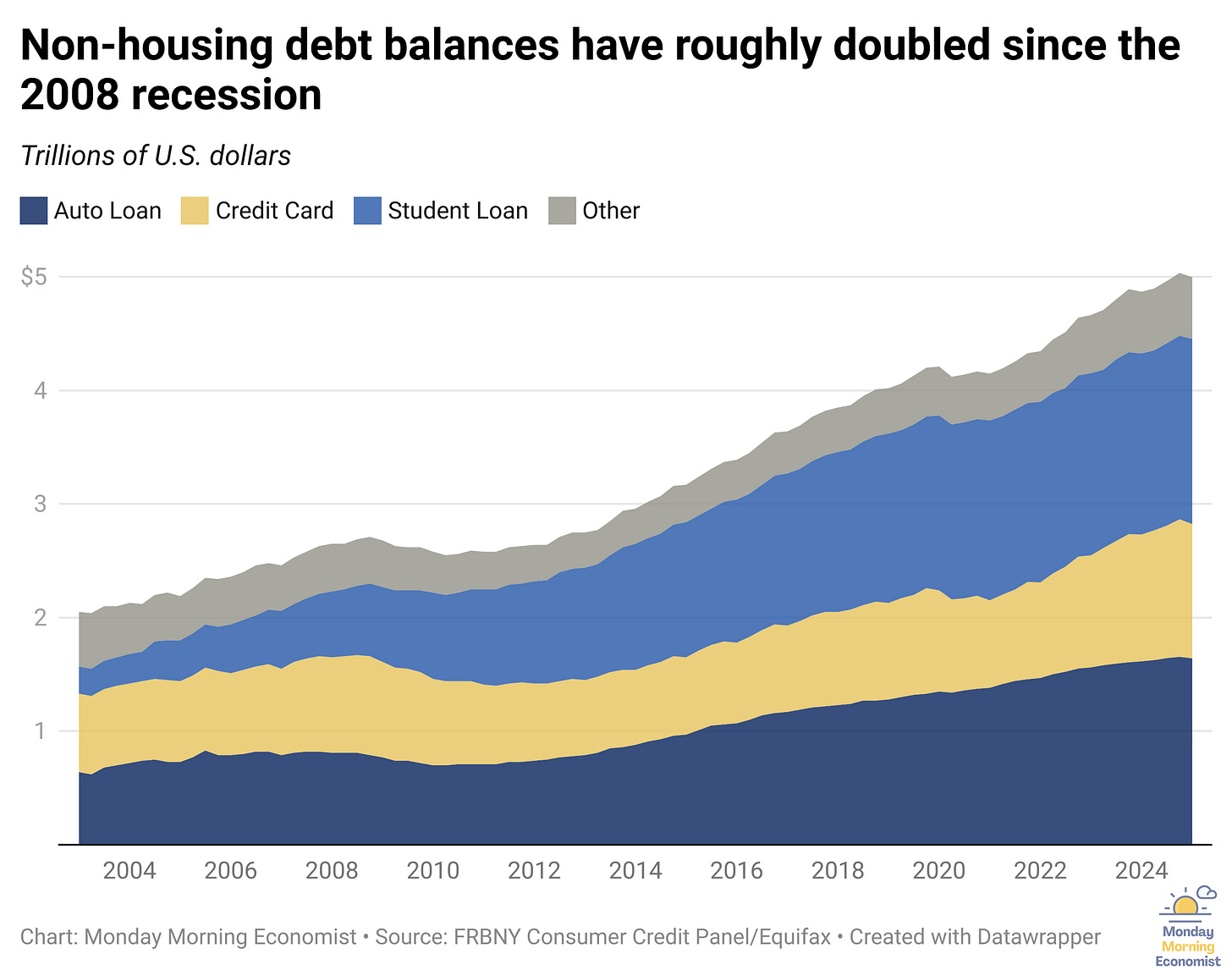

Lately, people have been searching for ways to save money, and not just in the usual ways. Credit card debt is back in the headlines, and consumer surveys show the highest level of concern about repayments since the pandemic. On social media, there’s a growing stream of videos offering side hustles, budget hacks, and increasingly creative tips for making ends meet.

One of the easiest suggestions? Check to see if the government owes you money.

States across the U.S. hold billions of dollars in unclaimed property, money that technically belongs to individuals but hasn’t been claimed. We’re talking about things like old paychecks, forgotten utility deposits, insurance refunds, and rebate checks that never made it to their intended recipients. Sometimes the business couldn’t find you. Sometimes you moved. Sometimes life just got in the way.

I check for unclaimed property a few times throughout the year. I’ve lived in four different states, so I’ve made it part of my routine to check each one every six months. While I’m at it, I’ll check for friends and family too. Over the years, I’ve found a few small windfalls: refund checks, lost wages, the occasional surprise from an old apartment.

But what makes unclaimed property interesting is that it exists at all. If people are rational and self-interested, as economists often assume, shouldn’t we know when someone owes us money?

But First, Go See if the Government Has Your Money

Before we start talking about economics, let’s look to see if your name is on one of those unclaimed property lists. It only takes a few minutes and might turn up enough money to treat yourself to dinner. You can check for yourself, your parents, your siblings, your friends—anyone who wouldn’t mind being surprised with a little cash.

Here’s how to do it:

Open your preferred search engine and type:

Look for the official state website, which typically ends in .gov

On the state’s portal, enter your first and last name to search.

(Skip the address field if you’ve moved)If something pops up, follow the state’s instructions to claim it.

(You may need to upload an ID or fill out a short form)Repeat for any other states where you’ve lived.

And hey—if you hit the jackpot, I’ll happily accept a 10% finder’s fee. Just kidding. (Sort of.)

Okay, now back to the economics of why this happens in the first place.

Rational People Don’t Forget About Money. Or Do They?

In standard economics, people are rational, self-interested decision-makers. If you’re owed money, you’d know it. That’s what the theory would suggest. You’d remember the deposit you put down on your last apartment, track your final paycheck from that summer job, and follow up on any refund check that never showed up. Economists even have a name for this hyper-logical version of you: homo economics.

But homo economicus doesn’t live in the real world—we do. Real people forget stuff. We move, change email addresses, toss out paperwork, or just never realize a company owes us anything at all. Behavioral economists describe this gap between perfect rationality and how people actually behave as bounded rationality. It’s not that we’re purposely making irrational decisions; we’re just working with limited time, incomplete information, and brains that can only handle so much at once.

And then there’s also a touch of overconfidence. Most people assume they’d know if someone owed them money. Why wouldn’t they? But that’s the problem. They forget about the $85 security deposit from a college apartment or the utility refund that was mailed to their old address. They forgot about those surveys they filled out for $25 and then never got in the mail. That misplaced confidence leads them to never even look.

So the money sits there—out of sight, out of mind.

The $10 That’s Not Worth $10

Even when people do know they’re owed money, they don’t always go get it. Why? Economists have a term for that, too: transaction costs.

A transaction cost is anything that makes an otherwise simple decision more time-consuming or annoying than it needs to be. It’s the effort and the annoyance of completing paperwork to get something back, even if it’s legally yours.

Let’s say your state owes you $10 from an old prepaid Visa card. Great! But to claim it, you have to fill out a form, print it, attach a copy of your ID, and drop it in the mail. Maybe you need to dig through old files to prove you once lived at that address. Suddenly, your $10 costs you 45 minutes, a printer, a stamp, and a willingness to remember where your envelopes are.

Those are transaction costs. And for a lot of people, it’s just not worth it. So the money sits there, unclaimed. Sometimes for years. Sometimes forever.

It’s the same reason people keep paying for gym memberships they never use—not because they want to, but because canceling is just annoying enough to put off. There’s even a comedian who does a whole bit about how hard it is to quit the gym, and he’s not wrong.

Final Thoughts

If you're worried about how to cover your next round of bills, you’re not alone. Consumer confidence is slipping, credit card balances are climbing, and the cost of everyday essentials isn’t going down. For households feeling the squeeze, even a small financial win can offer some relief.

Checking for unclaimed property won’t fix a budget in the long run. It’s a one-time fix, not a new income stream. But if there’s money out there with your name on it, why not go get it? It could be enough to cover a bill, buy groceries, or make an extra payment toward debt.

If you’re looking for other ways to cut back long term, it might be worth reviewing your monthly subscriptions. Those streaming services, apps, or memberships that quietly renew each month. Canceling just one or two could free up more than you’d expect over time.

These changes aren’t magic solutions. But they’re small, manageable steps. And right now, a few small steps in the right direction might be exactly what people need.

It only takes a few minutes to see if your state owes you anything. The money’s already yours—you just have to ask for it.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

The percentage of U.S. credit card accounts past due for 90 days was the highest in 12 years during the fourth quarter of 2024 [Payments Dive]

About 1 in 7 people have unclaimed property being held by a state [CNBC]

States returned $4,493,390,785 worth of previously unclaimed property in fiscal year 2024 [National Association of Unclaimed Property Administrators]

The index of consumer sentiment dropped to 50.8, down from 52.2 in April and hitting its second-lowest reading on record [CNBC]

Approximately 12.3% of credit card balances are more than 90 days delinquent, the highest rate since 2011 [Federal Reserve Bank of New York]