How 10 Seconds Became a Multi-Million Dollar Problem

A small security ritual adds up to a big economic burden when repeated by millions.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

A few weeks ago, the Trump administration announced a small but notable change to airport security: Travelers can keep their shoes on when going through TSA checkpoints in the United States. This isn’t much of a change for those of us who don’t travel very frequently. If you’ve got TSA PreCheck, you won’t notice any difference at all.

I jumped on the TSA PreCheck bandwagon years ago. A five-year membership costs only $75! At my small regional airport, it rarely matters. The lines are always short, and the experience is already low-stress. But the real value kicks in at larger airports on my way back home. Skipping the long lines, keeping my shoes, and breezing through security? Worth every penny.

Most people don’t pay for the privilege of TSA PreCheck, which means the shoe ritual has been a consistent, albeit minor, inconvenience for close to two decades.

To many, this policy update seems trivial. And compared to debates over tariffs or immigration, maybe it is. But in economics, scale matters. Small things that are experienced by 2 to 3 million people every day can add up in a big way.

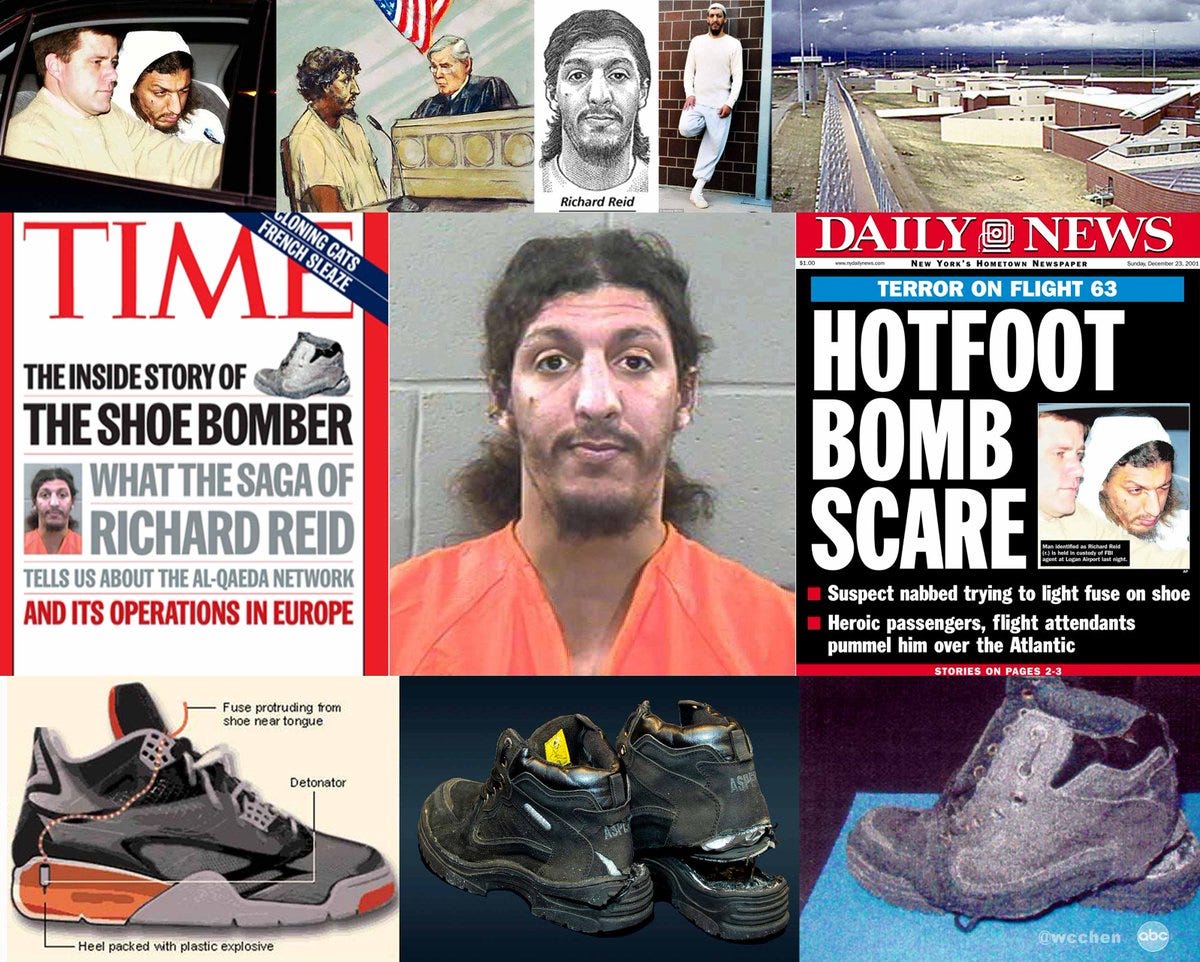

Why We Started Removing Shoes in the First Place

If you grew up flying after 2001, you might think taking off your shoes at airport security is just part of how flying always worked. But it wasn’t always this way.

The policy traces back to a single failed attack, just months after the most deadly attack on American soil. In December 2001, Richard Reid, later dubbed the “shoe bomber,” tried to ignite explosives hidden in his sneakers on a transatlantic flight from Paris to Miami. He was subdued by passengers and crew before anything detonated. No one was harmed. But the scare prompted a wave of new security measures across U.S. airports.

By 2006, shoe removal became standard for all passengers as part of a growing list of post-9/11 security rituals. Even as technology improved and scanners got better, the rule stuck around. Unless you had TSA PreCheck or traveled through a pilot program, your shoes were coming off.

That’s what makes the recent announcement feel like a genuine shift. The TSA has been testing new scanners that can detect explosives in footwear without requiring passengers to remove them. Now, the administration plans to expand that rollout, possibly paving the way for future changes to other small-but-persistent policies.

What’s the Cost of 10 Seconds?

It may not seem like taking off your shoes at security is really that big of a deal. Sure, it’s annoying, but it probably takes about 10 seconds out of your day. You toss them in a bin, walk through the scanner in your socks, and put them back on when you’re done.

But this is where thinking like an economist can help us see what’s usually invisible to others: the opportunity cost. That’s the value of what you could be doing instead. The time you spend fighting with your shoelaces is time not spent doing something else at the airport. You could be reading, working, relaxing, helping a child, or even just reducing the stress of travel.

And when millions of people are all losing those same 10 seconds every day, it starts to add up. So let’s do a little math, gently.

There was an average of 2.7 million passengers have passed through TSA checkpoints each day in July. If we assume roughly 30% of those passengers have PreCheck, it would mean about 1.9 million travelers went through the full security routine, shoes and all.

If each of those 1.9 million people allocated 10 seconds to dealing with their shoes, that’s 19 million seconds of wasted time. That’s probably hard to conceptualize, but it comes to more than 5,000 hours after converting it.

Even that may be hard to think about. If we take it a step further, that would be the equivalent of over 200 full days lost. Every single day. All because of shoes.

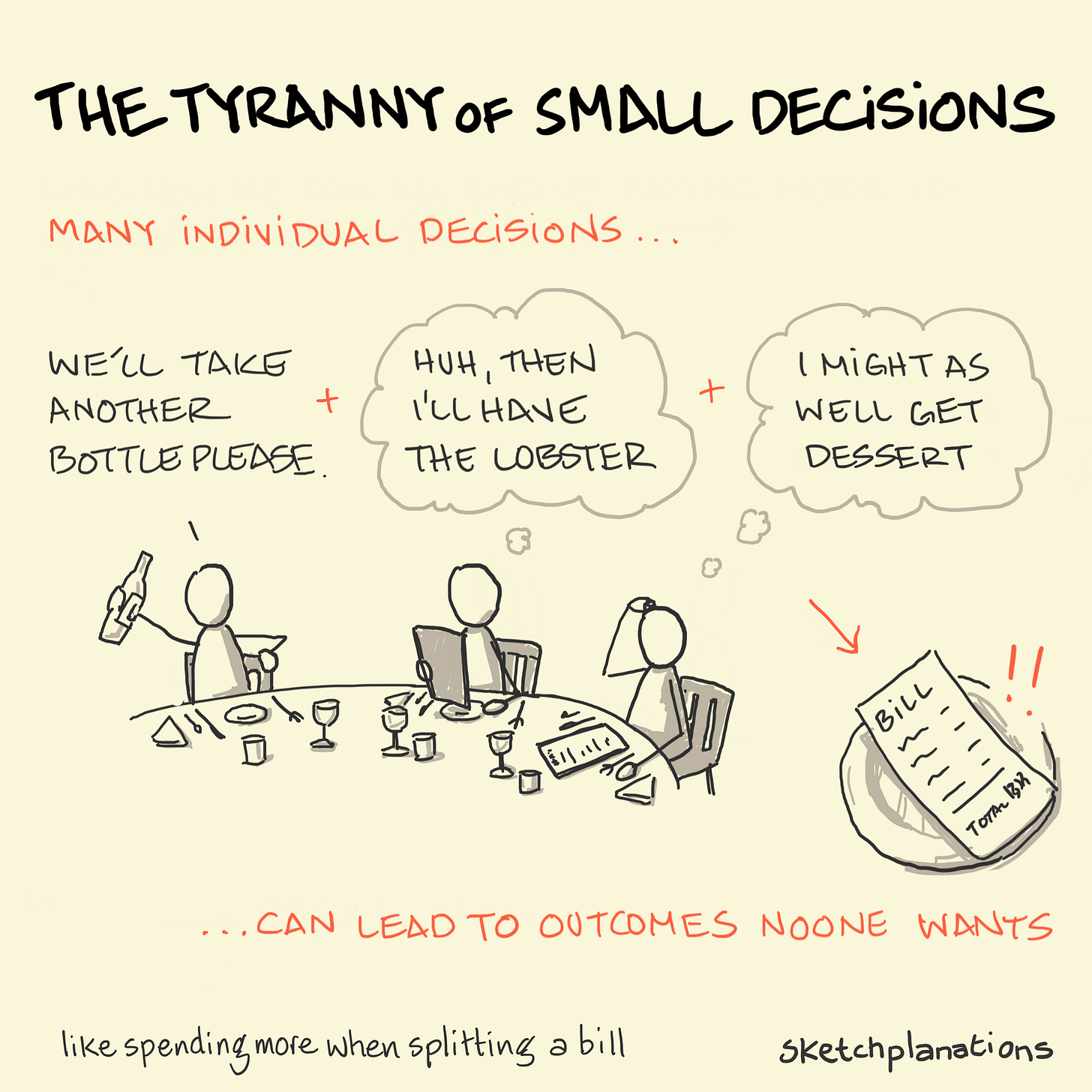

The Tyranny of Small Decisions

Economists sometimes refer to this line of thinking as the tyranny of small decisions. Though in this case, it’s not decisions that accumulate, but a small mandated action that scales across millions of people. Perhaps this is a new extension of Alfred Kahn’s 1966 theory, but the underlying idea still applies: even tiny frictions, when multiplied across large populations, can create surprisingly large costs for society.

No single traveler bore much of the burden of removing their shoes, but Americans collectively spent nearly 1.8 million hours last year on this single requirement. That’s nearly the same as 3 full lifetimes based on the average life expectancy of Americans.

Of course, that time we lost wasn’t equivalent to lives lost in a literal sense. But the concept can help us think better about how economists and policymakers assign value to time when evaluating policies and regulations. One concept is known as the value of a statistical life. The value reflects how much society is willing to pay to reduce small risks across large groups, like funding highway safety features or enacting environmental regulations.

Federal agencies like the Department of Transportation use this concept all the time. Their current estimate: about $13.7 million per life.

Let’s be careful here. I don’t think anyone literally died because of the shoe removal rule. But if we apply the same valuation logic to our three lifetimes’ worth of lost time, the imputed cost comes out to roughly $40 million per year. And that’s before we factor in the mental fatigue or the ripple effects of a slower security process.

It’s easy to dismiss something as “just a few seconds.” But a good economist will remind you that when you multiply small costs by millions of people, they’re not small anymore. It’s probably not too surprising that Americans were starting to question how effective the policy truly was.

Final Thoughts

Now that the rule is changing, it’s a good moment to ask: what else are we doing out of habit that carries a hidden cost? The Trump administration is also reviewing the 3.4-ounce (100 milliliters) liquid limit. It seems just as trivial a policy change to a lot of travelers.

This isn’t to say that policymakers shouldn’t focus on bigger issues. They absolutely should. But eliminating small, unnecessary burdens is smart economics. Especially when those burdens add up to the equivalent of millions of dollars in time, money, and attention.

So the next time you’re stuck in a line, filling out a form, or clicking through an extra screen, ask yourself: how many other people are doing this exact same thing right now? And what could we all be doing instead?

Thanks for reading the Monday Morning Economist. If you enjoyed this post, consider forwarding it to a frequent flyer, a fellow line-hater, or anyone who enjoys seeing the hidden economics behind everyday life. You might just change how they think about a 10-second delay.

When factoring in people who acquired trusted traveler status through other programs and affiliations, such as active military and Global Entry, the PreCheck rolls exceed 41 million [The Washington Post]

On October 4, 2002, Richard Reid pleaded guilty to eight terrorism-related charges, and he was sentenced to life in federal prison [Federal Bureau of Investigation]

In a survey of air travelers, a faster experience clearing security and/or customs was considered the third most impactful change that could be made to commercial air travel after lower prices and more comfortable seats [Airlines for America]

Alfred Kahn was commonly known as the "Father of Airline Deregulation," as he chaired the Civil Aeronautics Board during the period when it ended its regulation of the airline industry [Cato Institute]

Great post. My issue with the pre check fee is that given it saves society costs (and directly saves TSA costs), the government should be offering it for free (or even pay you to get it). The fee (like any fee) acts intentionally to dissuade you from getting it, even though benefits here are clear for all parties involved.

The chart, "Americans no longer believe rules on laptops, liquids, and shoes are very effective airport security measures" points to an interesting dichotomy. During the pandemic, ~50% of Americans believed masks were ineffective. 50% of Americans believed immunizations were ineffective (20% believed they contained Bill Gates' microchips*).

Just because Americans believe that rules on laptops, liquids, and shoes are effective airport security measures, doesn't make it true. There are experts across the federal government who are watching these plots, testing threat technology, and synthesizing intelligence to understand the risk to the American public.

Let's try to rebuild a society where we rely on expertise, rather than what Tik Tok told me to believe...

*2020 Economist survey