The $3 Tote Bag That Sparked a $400 Frenzy

Low prices create loyal customers—and booming secondary markets.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

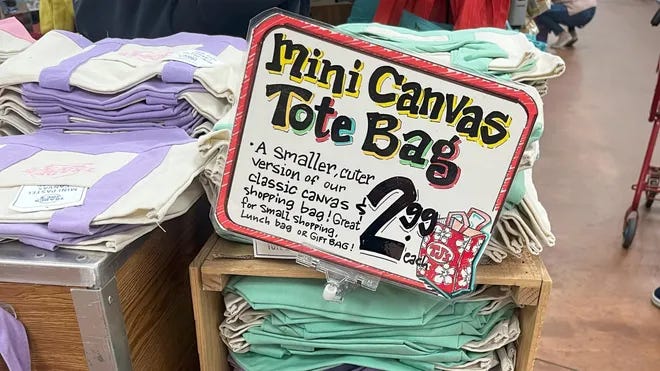

Last week, Trader Joe’s released its popular mini pastel tote bags—and almost immediately, they started popping up on resale sites like eBay and Facebook Marketplace. The bags retail for $2.99 in your local store. Online, some listings are asking as much as $400.

This feels unfair for many shoppers. Why should a $3 grocery tote suddenly cost more than a week’s worth of groceries?

But from an economics standpoint, the rise of a secondary market is a feature of a market system, not a flaw. For all the frustration secondary markets cause consumers, they help products get to the people who value them most.

Why the Shortage Happened

In everyday conversation, people often say there’s a “shortage” when something is expensive or hard to find. But to an economist, a shortage has a very specific meaning: it happens when a product’s price is set below the level where supply and demand naturally meet. When that happens, the quantity that people want to buy exceeds the quantity available at the store.

And that’s exactly what happened at many Trader Joe’s stores around the country. Priced at just $2.99, far more customers wanted the tote bags than Trader Joe’s had on its shelves. Some shoppers showed up early and bought multiple bags. Others showed up later and left empty-handed. From an efficiency standpoint, that’s a problem. It wastes time as people search for a product that’s already long gone.

The appearance of a secondary market is the market sending a signal: the original price was set too low for the level of demand that existed. Secondary sellers are simply stepping in to reallocate the bags to people who value them more, for a much higher price. It’s making the market for those viral tote bags more efficient.

Why Trader Joe's Sets the Price So Low

You may be wondering why Trader Joe’s didn’t just charge more for the mini tote bags in the first place. After all, they had every reason to expect that demand would outstrip supply—it happened last year, too.

The decision comes down to strategy. Trader Joe’s brand is built around offering good products at affordable prices. A $2.99 tote fits neatly into that identity. Pricing the bags at $25 or $50, even if the market would support it, would feel out of step with the store’s reputation for being accessible and unpretentious.

There’s also a goodwill factor. Offering a trendy item at a rock-bottom price builds loyalty, even if not everyone manages to grab one. Most customers don’t walk away blaming Trader Joe’s for the shortage, they blame the resellers. Meanwhile, Trader Joe’s reaps the benefits of viral publicity and the appearance of generosity.

Finally, simplicity matters. Trader Joe’s has built its business on avoiding complicated pricing tactics. No auctions, no luxury lines, no dynamic pricing—just straightforward low prices. Raising the price of a canvas bag just because it’s popular would break that pattern and risk alienating their loyal customers.

From Trader Joe’s perspective, and probably from many customers' perspectives, $3 feels like a fair price for a canvas tote. But fair pricing and efficient pricing aren’t the same thing. In this case, prioritizing fairness and branding has come at the cost of creating a predictable and preventable shortage.

Secondary Markets Improve Efficiency

When companies set prices below the market equilibrium, secondary markets step in to fill the gap. Resellers charge higher prices, but they also perform an important economic function: they allocate goods to the people who value them the most.

A $3 tote bag at Trader Joe’s might seem like a fair price to the customers, but it turned out to be incredibly inefficient at many locations. Meanwhile, the $50 or $100 resale listings seem unfair, but reflect a more efficient outcome. Those higher prices match buyers and sellers based on how much someone is truly willing to pay.

I’ve experienced a similar tradeoff myself. One of my favorite Trader Joe’s products is their Aglio Olio Seasoning Blend. But since I no longer live near a Trader Joe’s, getting my hands on it isn’t as easy as it used to be. I’ve had to buy it online in a secondary market, often paying triple what the store charges. Sure, it stings a little. But nobody forces me to pay the higher price. I choose to because the convenience and the product are worth it.

This tension between what feels fair and what works efficiently is at the heart of economist Arthur Okun’s idea of the efficiency-equity tradeoff. Okun argued that systems designed to be more “fair” often give up efficiency, and systems designed to be more efficient can feel less fair. Secondary markets make outcomes more efficient by reallocating scarce goods to those who value them most. But along the way, they upset our instincts about fairness. That’s especially true when we know that the original buyers were always planning to resell the product.

Final Thoughts

If Trader Joe’s had really wanted to prevent shortages, they could have. They had two straightforward options: raise the retail price closer to the true market-clearing price or produce enough tote bags to meet the expected demand. Either move would have made the resale market much smaller, maybe even irrelevant.

But they didn’t. And they’re not alone.

Plenty of companies seem to prefer the chaos that scarcity creates. Take movie theaters, for example. When Dune: Part Two and The Super Mario Bros. Movie released limited-edition popcorn buckets, customers lined up early to snag them for $25, only to watch them pop up online hours later for $100 or more.

The pattern is familiar: set a low price, keep the supply limited, let secondary markets do the messy work of reallocating goods to those who value them most. It’s not the most efficient way to satisfy demand, but it generates buzz and makes companies look generous even as some customers leave empty-handed.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

Trader Joe’s became the first grocer to offer reusable bags in 1977, printing them with the phrase “save-a-tree” [Today Show]

Aldi Nord, the European branch of the Aldi grocery chain, owns Trader Joe's [Yahoo!]

There are 608 Trader Joe’s stores in the United States as of April 15, 2025 [Scrape Hero]

In 2020, Trader Joe’s gross average revenue per square foot was about $2130—nearly double its competitors [Leaders]

Great article on market efficiency. Note, though, that Trader Joe's would have a third option. They could also have limited each individual purchase size, maybe two per customer.

Excellent read. It lines up nicely with what I say frequently in my small business classes, that maximizing profit is not the only reason to set a price. Providing a good product or service which is affordable and accessible to as many customers as reasonable is just as good of a guideline. (Obviously this changes a little bit when there's a fiduciary responsibility to stockholders; I'm not sure if TJ's structure includes that.)

Although if they know that the bags are popular, and they want to provide the best possible customer service, I do wonder why they didn't simply produce more of them so that more people could get one.