The Economic Blackout Probably Did More Harm Than Good

Good intentions don’t always translate into good outcomes.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

When The People’s Union USA announced its one-day “Economic Blackout” on February 28, the concept was straightforward: make a dent in big corporations’ bottom lines. Shoppers were encouraged to avoid spending money at major retailers, fast-food chains, and gas stations for 24 hours. The organizers framed the blackout as a show of economic force, a way for everyday Americans to remind corporate giants of the power of the purse.

Participants likely approached the boycott with good intentions. I’m sure plenty of people skipped their morning Starbucks latte or delayed an Amazon purchase. Some of those people may have switched to a local business instead. There’s a natural appeal to the idea that small actions, multiplied across millions of people, could influence corporate behavior.

But good intentions don’t always translate into good outcomes. The one-day boycott could have done more harm than good. Not to big corporations, but to the workers who can least afford it.

The Bigger Picture

The logic behind the "Economic Blackout" was that a sharp, sudden drop in spending would get retailers’ attention at a time when consumers are frustrated with high prices. However, a 24-hour dip in sales might seem like a bold statement, but the economic reality is far less dramatic. Economists measure a country’s aggregate demand (the total amount of goods and services purchased) over months and years, not just days.

Let’s say you normally fill up your gas tank on Fridays, but you wanted to participate in this boycott. You fill up your tank on Thursday instead. If enough of your neighbors do the same, your local gas station might notice the drop in sales on Friday. An empty tank won’t help you get to work or soccer practice.

But your local gas station would see above-average sales on Thursday as you and your neighbors fill up a day early. Their weekly sales are probably the same as the week before. The same logic would apply to the groceries you buy at Kroger or the household items you need to pick up at Target. If you're only shifting your spending to a different day, their weekly revenue remains the same.

For large corporations like Walmart and Target, a slight dip in sales on February 28th was likely made up for with higher sales on the days before and after the boycott. Their year-end revenue (and our nation’s aggregate demand) remains unaffected. There is a big difference between a temporary shock and a lasting change. One barely makes a ripple, while the other can reshape the economy.

For all the effort put into the boycott, the net effect on corporate bottom lines was likely close to zero. However, the same can’t be said for everyone.

Who Really Pays the Price?

While this particular boycott was aimed at big corporations, the real impact likely hits much closer to home. Many of the people affected weren’t CEOs or shareholders. They were the hourly workers who relied on steady shifts to make ends meet.

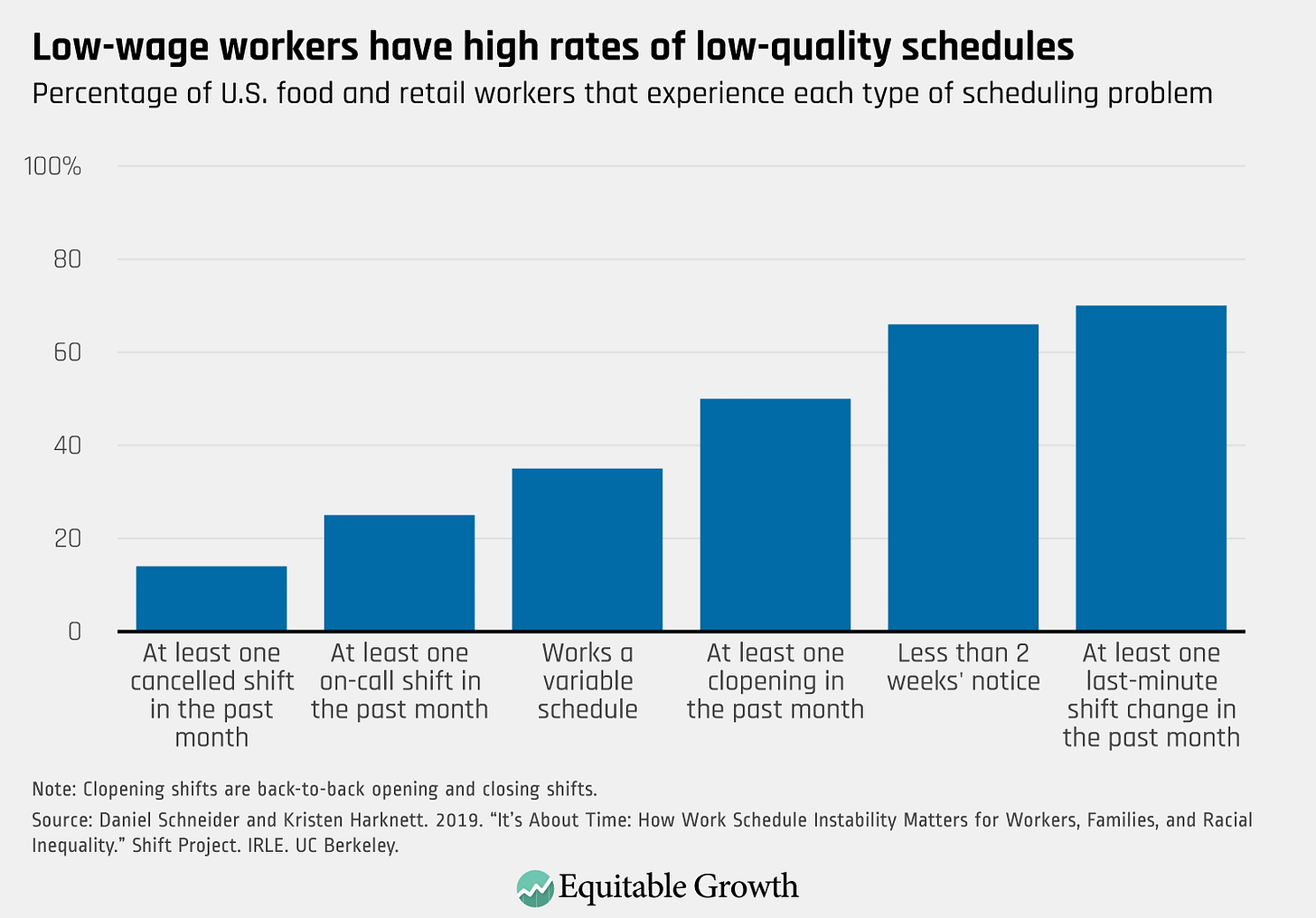

I remember working in fast food when I was younger. My schedule was typically set a week in advance, but it was always subject to the mercy of each day’s sales. When business was slow, my manager would send someone home early. It wasn’t my fault that business was slow that night, but I still paid the price for it. A six-hour shift would turn into three, and my paycheck at the end of the week was smaller than I was counting on.

The frustrating part? During unexpectedly busy shifts, we weren’t calling in extra people to help out. There was no telling in the moment if our sudden surge in business would last all night, so there was no reason to call someone in to help. Instead, those of us on the clock were expected to do more with less, often without any extra support or pay.

This kind of income volatility is a constant stressor for low-wage workers. If the boycott led to slower sales on February 28, some workers were likely sent home early without pay. If sales rebounded the next day, those workers were likely stretched thin. The end result? Workers who needed a full shift missed out on income, while others faced heavier workloads without additional pay or support.

The economic pain, if there was any, wasn’t evenly distributed. While big corporations likely saw their sales shift from one day to another, workers couldn’t do the same with their pay. Those lost hours weren’t coming back, and for many, that will mean tough choices when the bills come due.

The irony is hard to miss. Boycotters may have intended to make a statement against big business, but in practice, they may have hurt the very people who have the least control over the business.

Final Thoughts

One-day boycotts may grab headlines, but real change requires more than a temporary pause in spending. If people want to influence corporate behavior, the focus needs to shift from one-off actions to sustained changes in purchasing habits. True economic pressure comes when consumers not only avoid a business for a day but also make lasting adjustments to where and how they shop.

Local businesses won’t adjust their hiring policies if they see increased sales for a day or even one week. They may make some changes if they were to see a sustained increase that lasts for several months. Only then would they hire more staff, expand their services, and contribute more to the local economy. But at the same time, large corporations that see a sustained drop in revenue might cut back on staffing or even close locations. That would mean job losses for some residents.

These big corporations also employ real people, often your neighbors, friends, and family members. Those jobs might not always be ideal, but for many, they are critical sources of income and stability. This isn’t to say that boycotts are inherently bad or that those participating don’t have valid concerns.

Instead of aiming for a quick win, consumers who want to make a difference could focus on building long-term habits that reflect their values. That can mean buying from companies with strong ethical practices, supporting local businesses regularly, or reducing consumption overall.

If the ultimate goal is to create a better, fairer economy, the path forward likely involves a lot more than skipping a shopping trip for a day. The reality is that corporate giants can weather short-term disruptions. They have the resources to absorb a bad day. But for workers on the front lines, a slow day at work might mean a half-empty paycheck.

There are 4,078,000 retail sales workers employed in the United States, earning a median pay of $16.30 per hour [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

Walmart annual net income for 2024 was $15.511B, a 32.8% increase from 2023 [Macrotrends]

At the end of fiscal year 2024, Walmart employed approximately 2.1 million people around the world and approximately 1.6 million people in the U.S. [Walmart]

Between October 2022 and June 2023, the share of Americans who say that "large corporations seeking maximum profits" deserve "a lot" of blame for inflation rose 9 percentage points, from 52% to 61% [YouGov]

Could've been titled "economic illiterates' ill-conceived plan predictably fails."

I am not so gracious as to call their intentions good. The kind of people calling for these 24 hour boycotts are unserious people and should be rebuked roundly.

These points are well taken, long term strategic thinking more than one day boycotts is required to work towards a better, more fair economy.

Which is why I'm perplexed that there is no mention of supporting unionized labor and companies who negotiate in good faith with them, in no small part, for more predictable, and less just-in-time scheduling.