Tariffs, Trade, and What We Often Forget About U.S. Exports

We talk a lot about tariffs on imports, but it's easy to forget that retaliation can hit U.S. exports just as hard.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

One of my earliest memories of family vacations was a visit to Ciudad Juárez, just across the border from El Paso, Texas. I still have a Mexican blanket from that trip, a small but constant reminder that international trade is a common part of our lives. I bought that blanket as an import—something made in another country and brought into the U.S. Over the past week, there’s been a lot of talk about tariffs and what they mean for Americans buying imports. It seems we haven’t taken the time to consider the other side of the trade equation: exports.

You’ve likely heard ongoing complaints about the country’s trade deficit—it means a country buys more from abroad than it sells to other countries. The U.S. runs a trade deficit with many nations, including Mexico and Canada. But here’s the thing: a trade deficit isn’t inherently bad.

Consider your local grocery store for just a minute. You buy things from them every week—milk, eggs, vegetables—but the store doesn’t buy anything from you. In trade terms, you have a trade deficit with the grocery store. But does that mean you’re getting a bad deal? You could grow your own vegetables, raise chickens for eggs, and buy a cow for milk, but that would be expensive, inefficient, and incredibly inconvenient. Instead, you specialize in what you do best—your job—and trade a portion of your income for groceries.

International trade works the same way. Americans aren’t forced to buy things from Mexico and Canada. They could purchase products exclusively made in America, but they often don’t—because those products are more expensive. Trade allows Americans to buy things cheaper than if they tried to make everything themselves. Meanwhile, other countries buy American-made goods, supporting millions of U.S. jobs.

And in case you haven’t heard, we do export a lot of goods and services. Last year we exported a little over $3.19 trillion worth of goods and services. And just over 33% of the goods we export when to two countries: Canada and Mexico.

What Happens When We Place Tariffs on Imports?

A tariff is simply a tax on an imported good. If the U.S. places tariffs on different products coming from Mexico or Canada, it raises the price of those goods for American consumers. That part is straightforward. A tariff makes the avocados we import from Mexico more expensive, and you pay more at the grocery store.

But tariffs don’t just affect what we buy directly. They also make things more expensive down the supply chain. You’ll see a higher price for avocados at the store, but the guacamole at your favorite Mexican restaurant will also be pricier. Even if something is made in the U.S., if it relies on foreign inputs, the final price goes up.

This is what’s gotten most of the attention over the past week—higher prices for consumers. But the problem is magnified when we remember what comes next: retaliatory tariffs.

Trade isn’t a one-way street. When the U.S. imposes tariffs, other countries hit back with tariffs of their own. And those retaliatory tariffs impact industries that employ Americans.

Take American liquor. When the U.S. placed tariffs on Canadian and Mexican goods, Canada retaliated by removing American liquors from their stores. The Premier of Ontario announced that the province would no longer carry American liquor—roughly $1 billion in lost sales per year. Other provinces have followed suit.

What does that mean in practice? Fewer sales for U.S. liquor companies like Brown-Forman, the makers of Jack Daniel’s. That doesn’t just impact the workers distilling whiskey—it also impacts the accountants, marketers, sales teams, and even janitors. The entire business scales down.

But that’s just an example of one industry. Now multiply that across all the companies affected if Canada and Mexico retaliate if the tariffs aren’t removed when the pause ends. The impact on exports quickly adds up. It’s why the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal called this the dumbest trade war in history.

Retaliation Hits U.S. Exports Hard

When Mexico or Canada retaliates with tariffs, it doesn’t just make it harder for U.S. businesses to sell abroad—it can alter entire supply chains. Companies that export everything from fuel to food to factory parts suddenly find their products less competitive in a global marketplace.

But let’s stick with Canada and Mexico for today. In 2022, the U.S. exported $602 billion worth of goods to our neighbors. By 2024, that number had grown to $683 billion. This isn’t coming just a handful of industries—it’s a sprawling network of trade, covering everything from refined petroleum to corn to car parts.

I know the chart is hard to see, but that’s what happens when you export as many different goods as a country like the United States exports. You can get a better view of the smaller categories by checking out the Observatory of Economic Complexity, but here are a few of the largest export groups by total value in 2022:

Refined petroleum and petroleum gas account for about 12.5% of all exports to Mexico and Canada.

Cars and delivery trucks represent just over 5% while motor vehicle parts contribute another 4.72%.

And even corn—just that one crop—accounts for 1% of total exports to our neighbors.

These numbers tell an incredibly important story: U.S. exports are deeply embedded in the North American economy. Disrupting trade agreements doesn’t just mean paying more for imports—it means fewer orders for American businesses, lower production, and fewer jobs.

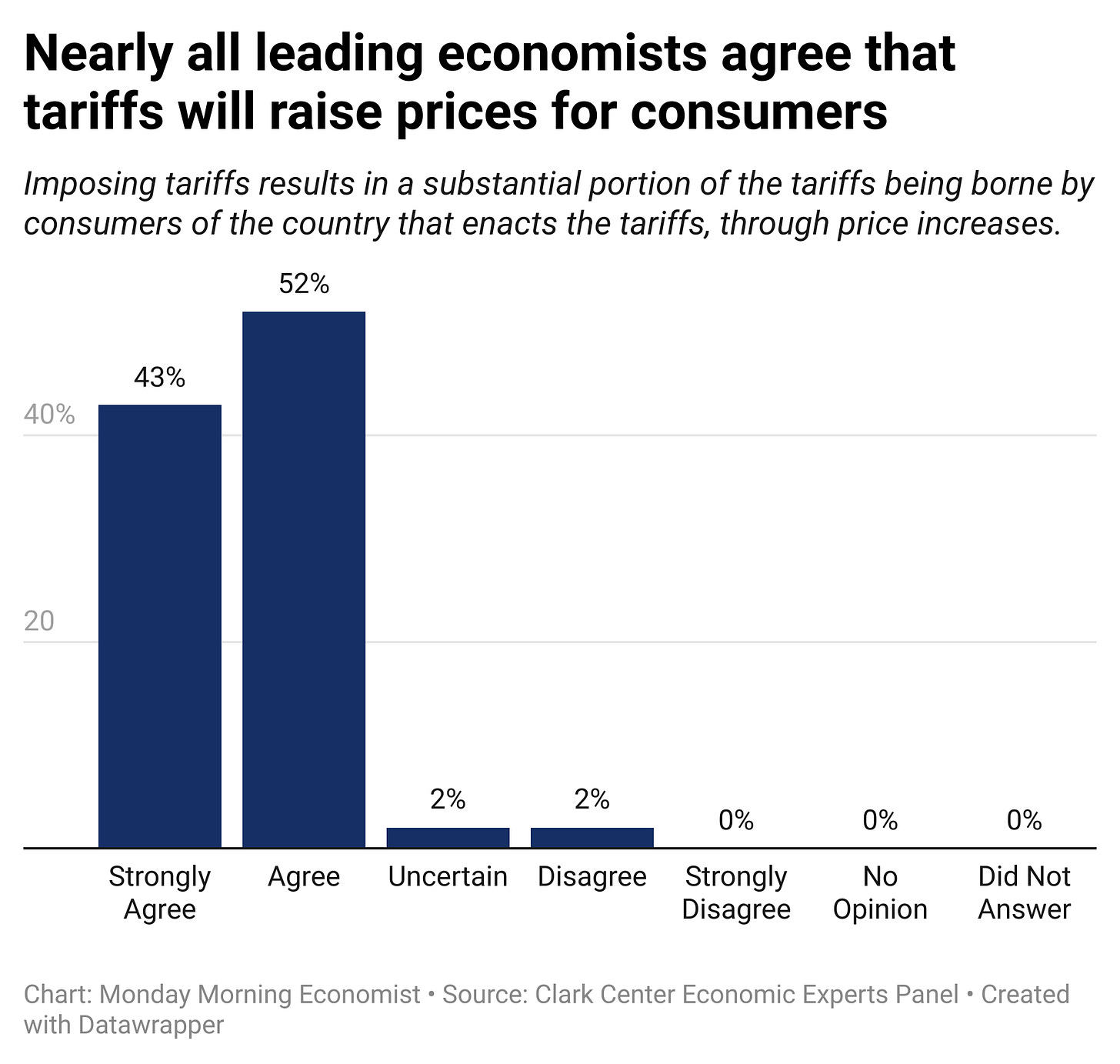

And the consequences extend beyond our borders. A recent poll of leading economists found that the vast majority believe that new tariffs and trade wars will slow global growth over the next five years. Tariffs raise the price of things we purchase, but trade wars make it harder for the U.S. to sell abroad, harder for companies to hire, and harder for the economy to grow.

Final Thoughts

It’s easy to focus on what we buy from other countries, but we can’t forget what we sell. A trade deficit doesn’t mean the U.S. doesn’t export—it just means we import more than we export. With a third of our exports going to just two countries, the effects of this spat with Canada and Mexico can ripple through the economy quickly.

But let’s take this a step further. If tariffs reduce imports, wouldn’t that mean more demand for American-made products? Yes, but only up to a point. Domestic producers would likely expand, offsetting some of the job losses from falling exports. But there’s a tradeoff: American-made products would become even more expensive than they already are. If everything costs more, people buy less overall.

And don’t be fooled by the idea that the government could lower income taxes to offset higher prices. Every American pays the higher prices from tariffs, but not everyone pays the same income tax rate. In 2022, the bottom half of earners paid an average of just 3.7% in federal income taxes. If their grocery bill, gas, and everyday expenses increase by 25%, a small income tax cut won’t make up the difference.

Our income tax system is progressive—higher earners pay a larger share of taxes. But tariffs are regressive—they hit lower- and middle-income Americans the hardest. So the next time you hear about tariffs, ask yourself: Who really pays the price?

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 6,400 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

The United States has run a persistent trade deficit since the 1970s—but it also did throughout most of the 19th century [Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis]

The United States has a trade surplus when it comes to services, exporting $1.1 trillion and importing $814 billion in 2024 [U.S. Census]

Each one-billion dollars of exports is estimated to support 4,100 jobs[International Trade Administration]

Tariffs on Mexico, Canada, and China are estimated to reduce GDP by 0.4%, reduce employment by 344,000 jobs, and result in an average tax increase of $830 per US household [Tax Foundation]

Henry Hazlitt has a sad

Wielding tariffs (or the threat thereof) as a foreign policy cudgel works for that purpose only because we have a dominant economy, and what's merely painful to us can be crippling to other countries. Still a hard sell for me to think economically screwing the citizens of non-belligerent countries is good policy.

Great work as usually. Thanks for the shoutout