The Penny Problem Isn’t Solved—It’s Just Moved to the Nickel

Eliminating the penny might sound like a smart way to cut costs, but when nickels are even more expensive to produce, are we really saving anything?

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Do you remember the last time you paid for something with cash? Maybe you handed over a $20 bill and got a handful of coins back. What did you do with them? Toss the change in a donation jar? Leave the pennies behind in that little tray at the register? Maybe you shoved them in your pocket, only for them to end up in a coin jar at home—the one that keeps filling up, because so few people bring their coins back to the store.

When I was a young kid, most things were purchased with cash. That meant we all ended up with a lot of change. Instead of carrying a pocket full of coins, most of us tossed them in a jar somewhere around the house. My parents stashed their coins in one of those giant office water jugs full of coins. And every so often—usually when times got a little tight—we would gather around the kitchen table, dump out the jug, and roll up the coins to exchange at the bank.

Those jugs take a lot longer to fill up these days. With credit cards, debit cards, and mobile payments, physical money just doesn’t move through the economy the way it used to. The velocity of coins—the rate at which money changes hands—has slowed way down. I still have a jar of coins sitting in my kitchen and a bag of them stashed in my car door, but I don’t remember the last time I considered using them. Even the lowly parking meter takes cards now.

So if coins aren’t circulating like they used to, why are we still making billions of them each year? It’s a question politicians have been asking for decades, but perhaps it’s a question we’re finally ready to address. Last week, President Trump called for eliminating the penny. He didn’t call for it because of its declining use, but rather because of its rising cost. It turns out that producing a single penny costs about 3.7 cents. In 2024 alone, the government “lost” $85.3 million producing billions of pennies.

On the surface, cutting the penny sounds like an easy budget fix. But getting rid of the penny doesn’t necessarily mean the government will save a lot of money. In fact, it may even shift the problem to the next lowest denomination. But here’s the problem: the nickel is even more expensive to produce.

So, if the penny is a waste of money, and the nickel is an even bigger waste… why are we still making them?

How Would This Actually Work? Ask Canada.

Before we get into the implications of killing the penny, you may have some questions about the logistics. Prices won’t suddenly jump up just because we ditch the one-cent coin. Thankfully, we can look to our neighbors up north on how this works. Canada stopped distributing pennies back in February 2013, and guess what? The economy didn’t collapse.

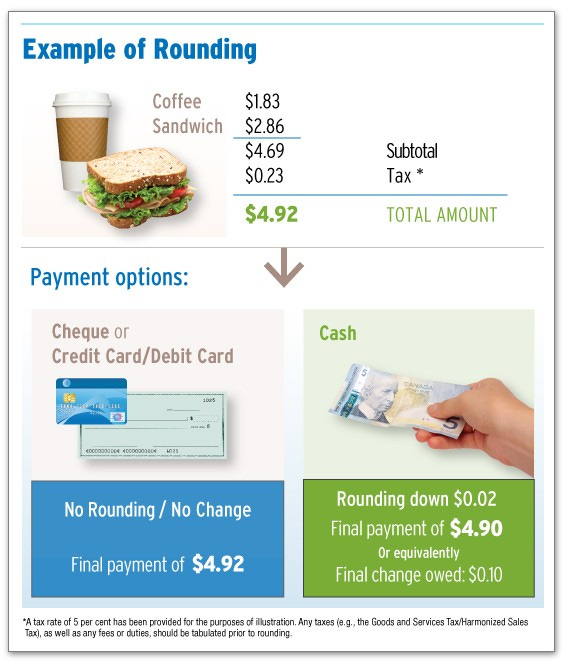

Whenever their penny policy went into place, businesses were encouraged to round cash transactions to the nearest five cents. For example, if your total comes to $10.92, you would pay $10.90 if paying in cash. If your total was $10.97, it rounds up to $11.00. Over time, the rounding mostly cancels out, so neither businesses nor consumers are losing money.

But it’s important to remember that this policy only applies to cash transactions. If you’re paying with a credit or debit card, nothing changes—digital payments still process the exact amount, down to the cent. The concept of the penny still exists, but the physical coin will slowly disappear.

For those who primarily use cash to pay for everyday things, the shift means that nickels will take on a bigger role in daily transactions. And that’s where the real problem begins.

Are We Trading One Bad Coin for Another?

Getting rid of the penny might seem like a no-brainer—it costs more to make than it’s worth, and hardly anyone uses it. But there’s a catch: eliminating the penny would likely increase demand for the next smallest coin—the nickel. And from a cost perspective, the nickel is an even worse deal for taxpayers.

Right now, each penny costs about 3.7 cents to make, meaning the government loses roughly 2.7 cents per penny minted. A nickel? Each one costs over 12.5 cents to produce. While the penny costs relatively more as a percentage, nickels cost more as an absolute value. Every time the U.S. Mint produces a nickel, it results in a loss of 7.5 cents—more than twice the per-unit loss of a penny.

But this is where things get tricky. The mint doesn’t currently produce many nickels. It needs to produce billions of pennies because so few of them circulate through the economy. It was the lack of circulation that caused the “coin shortage” during the pandemic, not an actual shortage of coins.

In 2024, the U.S. Mint produced 3.1 billion pennies, but only 202 million nickels. In total, that resulted in a loss of $85 million on pennies and $17 million on nickels. Removing the penny will likely require cash-based consumers to demand more nickels to fill in the gaps in cash transactions.

The Mint won’t need to replace every lost penny with a new nickel, but an increase in nickel production means an increase in demand for the raw materials used to make them—primarily nickel and copper. That increased demand could drive up the cost of those metals, making the nickel even more expensive to produce than it already is.

And that’s the dilemma: we might save money by cutting out the penny, but we could end up spending even more money to produce nickels.

If the Mint increased nickel production fivefold to help replace lost pennies, we’d be right back where we started—losing the same $85 million we were trying to save. And that’s assuming the cost of making a nickel doesn’t go up due to increased demand for materials.

So we’re left with a tough question: if eliminating the penny just shifts the financial burden to the nickel, is this really a win? Or are we just trading one money-losing coin for another?

Final Thoughts

You may be wondering if all this will actually save the government any money. Not really. Eliminating the penny sounds like an easy cost-cutting measure—after all, the U.S. Mint lost millions producing pennies last year. But we should add a little context: the federal budget last year was $6.8 trillion. If we were to treat the U.S. budget like it was a $100 bill, the potential savings on removing the penny would save us about 0.00125 dollars (or about 1/10 of a penny). Most accounting software would round that down to 0 cents.

But there’s more context to consider in all of this. The U.S. Mint profits from making coins overall. The technical term for this is seigniorage—the difference between how much it costs to produce money and its face value. While the government loses money on pennies and nickels, it more than makes up for it with quarters, dimes, and dollar coins, which are much cheaper to produce relative to their value. The profits on the quarters produced last year make up for all the losses on pennies and nickels. In the grand scheme of things, the penny may be a loss leader to get people to use other coins instead.

The real savings from eliminating the penny likely comes from time. How many minutes have you wasted digging through your pocket for exact change? How often have you stood in line behind someone slowly counting out pennies? It may seem insignificant for one person, but across millions of transactions every day, those extra seconds add up to a meaningful loss in productivity.

So if there’s a strong argument for getting rid of the penny, it’s not about the cost—it’s about efficiency. But unless we rethink the nickel, we might just be swapping one problem for another.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 6,500 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

The mint has first issued a penny in 1793 after the Coinage Act of 1792 was passed [U.S. Mint]

Our current pennies are made up of copper-plated zinc (97.5% zinc, 2.5% copper and weigh 2.5 grams [U.S. Mint]

The share of payments made with cash decreased to 16%, though it remained the third most-used payment instrument behind credit and debit cards [U.S. Federal Reserve Bank]

While there may be support for eliminating the penny, only 33% of voters believe the U.S. government should stop producing new nickels even though the cost outweighs the face value [Data for Progress]

Perhaps encourage more use of coins by dropping the dollar bill and using a dollar coin. A dollar bill only lasts about 7 years anyway. Or maybe create a special event / day nationwide for people to turn in coins.

The obvious solution would be to make the penny worth one penny's worth of metal. And the nickel would be worth one nickel's worth. And so on. We could have a whole monetary system based on the value of some type of metal -- hey, wait a minute!

Fun fact: the largest amount of US coinage you can have without being able to make exact change for a dollar is $1.19