Pull Up a Parking Chair

What a plastic chair can teach us about property rights after a snowstorm

You’re driving down a residential street after a heavy snowstorm, scanning both sides and hoping for an open spot. Most of the curb is buried, but then you see it. A clean rectangle of pavement carved out of the snow. Someone clearly shoveled recently, and your car would fit perfectly.

And right in the middle of it sits a chair.

There’s no official sign attached. It’s just a chair sitting in a public parking spot, as if it belongs there. So what would you do?

If you live in cities like Pittsburgh or Boston, or across parts of the Upper Midwest and Great Lakes, this scene probably feels familiar. Someone who lives on the street shoveled out that spot and marked it. The chair represents a claim, and you likely already have strong opinions about it.

If you live almost anywhere else, the practice might sound completely unhinged. Why should a plastic chair turn a public street into private property?

That question turns out to have a surprisingly good economic answer.

An Iconic Regional Tradition

Before we get to the economics, flip the story around for a moment.

Put yourself in the snow boots of the person who spent an hour digging their car out of a snowbank. They shoveled all the way down to the pavement. They cleared the curb. They created a usable parking spot where one didn’t exist before.

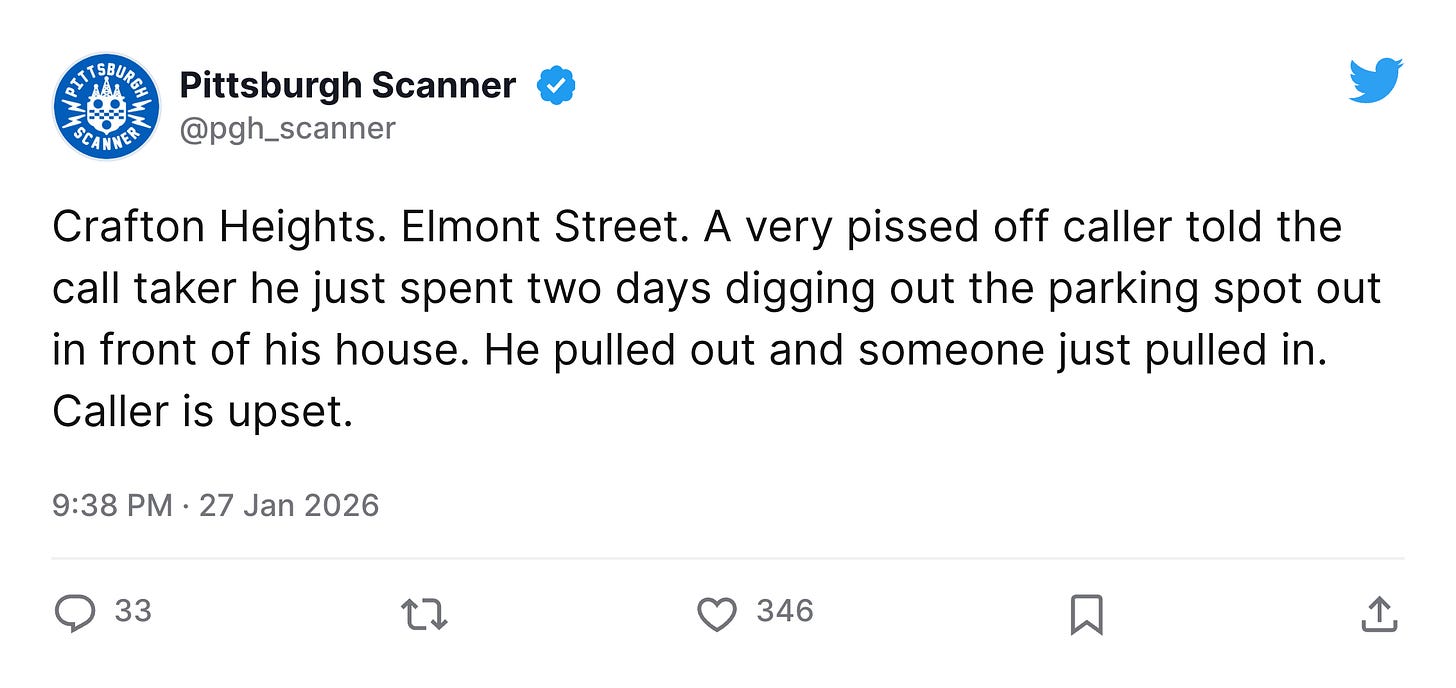

They ran a quick errand to restock their bread and milk for the next big storm in the forecast. When they come back, the spot is gone. Some jagoff swooped in and parked there, enjoying the benefits of work they didn’t do. That driver didn’t break any laws. The shoveler just has bad luck.

That experience explains why the parking chair exists.

In many Northeastern cities, the chair turns effort into a temporary claim. It’s not a legal right, but it is an understood one. The object in the spot communicates something simple: someone invested real labor here.

Economists would describe this as an informal property right. The space actually belongs to the city, but social norms temporarily assign control to the person who created the value. The chair, cone, or crate is just a marker. Enforcement comes from shared expectations about fairness and effort.

Locke, Snow Shovels, and Labor

The intuition behind this practice goes back a few centuries. John Locke was a philosopher writing in the late 1600s who was interested in a basic question: how do things become owned in the first place?

His answer was fairly simple. When resources are unowned, people gain legitimate claims by mixing their labor with them. If you take something that doesn’t already belong to someone else and improve it through effort, that effort creates a moral claim. This idea is often referred to as the labor theory of property.

The intuition is that labor transforms resources by creating value. And once value is created, people tend to believe the person who did the work deserves some control over the result. That intuition shows up clearly after a snowstorm.

A snow-covered parking spot isn’t very useful, but a shoveled one is. Digging changes how the space is perceived. The clean spot feels earned, rather than just another piece of the street. People are more willing to respect claims based on effort, even when the underlying resource is public.

Pittsburgh’s mayor put it plainly when he reminded residents to respect the chair:

Enforcement Without Enforcers

None of this works unless other people go along with it. There are no parking chair police, and you won’t get a ticket for moving one. Some cities explicitly ban the practice of putting chairs out in the street, while others quietly tolerate it or emphasize shared responsibility among neighbors.

The sanctions for violating a parking chair are usually social. A dirty look from a neighbor. A note on a windshield. An awkward confrontation with someone you’ll see again tomorrow. In residential neighborhoods where people interact repeatedly, those costs matter. On an anonymous downtown block, much less so.

The object itself helps, too. A handwritten sign that says “Do Not Park” wouldn’t last long in the environment. It’s also easy to ignore and easy to argue with. A chair is different. It’s mildly costly to remove. You have to stop, get out of your car, and move it. Even small costs can deter behavior when paired with uncertainty about what may come next.

A chair is a bit more credible. It signals that someone took time to put it there, and that a human behind the claim is paying attention.

Put it all together, and you get a system that functions without formal enforcement. Labor creates a claim. Social norms back it up. And a cheap, physical object helps coordinate behavior.

Final Thoughts

So are parking chairs efficient? Maybe.

They likely increase shoveling. When people believe they can temporarily claim a cleared spot, they are more willing to put in the effort quickly and thoroughly. Streets clear faster. Cities recover more quickly after storms.

But efficiency is not the same as fairness. Parking chairs reward people with more time, strength, or physical ability. They disadvantage newcomers who don’t know the rules. Visitors are left confused. And the people most likely to need close parking are often the least able to shovel for it. That tension is a lesson for another day.

The parking chair is more than a quirky regional tradition. It’s a reminder that economics shows up in everyday life, even without formal rules. Property rights don’t always require paperwork. Enforcement doesn’t always require police. Sometimes, legitimacy comes from effort rather than law.

Know someone who has strong opinions about parking chairs? Feel free to share this with them. Just don’t move anything that isn’t yours.

Major Northeastern cities like Boston, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland average 40–80 inches of snow per year [Farmer’s Almanac]

A fluffy or dry snow weighs about 4 pounds per square foot, while a wet snow is close to 13 pounds per square foot [WTHI TV]

Chicagoans requested 10,132 dibs object removals from Jan. 1, 2022, to Jan. 1, 2026, according to 311 data [Axios]

Boston explicitly allows “space savers” for 48 hours after a snow emergency [CBS News]

The Pittsburgh tradition goes back to at least the 1950s (one shows up in an old photograph) and maybe even further [Pittsburgh Post-Gazette]

Ooh -- Locke! Pierre-Joseph Proudhon deconstructed Locke in his book "What is Property". He wondered how Locke found it possible to turn from "labor results in property" to "and it's OK to transfer property to one's heirs".

Great use of "jagoff", but you underutilized the word "dibs".