Houston is Fixing a Problem Using a Key Economic Concept

The nation’s fourth-largest city used the concept of comparative advantage to help move more than 25,000 homeless people directly into apartments and houses around the county over the past decade.

In a recent New York Times article, Michael Kimmelman outlines how Houston has reduced homelessness by 63%! The nation’s fourth-largest city spent the past decade moving more than 25,000 homeless people directly into apartments and houses around the county. According to local officials, the overwhelming majority of them have remained housed after two years. More modest metrics show that Houston has done more than twice as well as the rest of the country at reducing homelessness. What makes Houston’s approach better than the other cities? The city first recognized that there were a lot of organizations with the same goal and then focused on using applying the theory of comparative advantage:

Houston has gotten this far by teaming with county agencies and persuading scores of local service providers, corporations and charitable nonprofits — organizations that often bicker and compete with one another — to row in unison.

At the start of the city’s reformation, Houston had one of the highest per-capita homeless counts in the country. The city was spending millions of public dollars placing homeless Houstonians in jail for intoxication. Meanwhile, dozens of public and private local aid organizations were working on their own organizational objectives. The groups were often competing for federal funds, duplicating similar services, not sharing information, and ultimately not housing very many people.

It’s similar to the problem facing countries who want to produce everything themselves without relying on trade. While it might be possible for some countries to produce everything themselves, it doesn’t maximize total welfare. Countries are better off collectively if they specialize in things they are good at relative to others and trade those things with each other. Under this arrangement, the two countries consume more than before. Houston took an “international trade” approach to homelessness and asked local organizations to work together and focus on what each organization is relatively good at instead of each organization trying to do everything by themselves:

Thao Costis, who runs a homeless service provider in Houston called SEARCH, said that back then her organization, like many in the city, was trying to do everything: outreach, case management, child services, employment training, paying rent to landlords to house clients. “SEARCH was $1 million in the hole,” Ms. Costis remembers, “and the people who most needed help weren’t getting it.”

But how should organizations in Houston decide what parts of the solution to specialize in? Specialization is based on a concept known as opportunity cost. It requires those organizations to weigh the gains of an extra hour of one activity compared to the lost production from not doing the other activity. By identifying the activity that has the smallest “loss per gain” the organizations can identify their comparative advantage.

Houston is a big city and there may actually be organizations that are better at doing everything when you compare each part of the process–they process more cases each day, their case managers have more meetings each day, and they raise more funds each day. These organizations hold an absolute advantage in each activity over all of the other organizations. Thankfully, even organizations with an absolute advantage can still benefit from specializing and focusing on their comparative advantage. That’s what more than 100 organizations in Houston realized when they came together to form The Way Home. They appointed a nonprofit organization known as the Coalition for the Homeless of Houston/Harris County as the lead agency.

While the group has done really well over the past decade, there were still some organizations that chose not to participate for various reasons. They may not have a single objective of lowering homelessness, but rather were trying to achieve multiple different goals that ran counter to The Way Home’s goal of “housing first.” These organizations, food banks and religious groups, made prayer or sobriety conditions for housing and thus did not join the group. Trade maximizes social welfare when both parties have similar objectives.

Once The Way Home started working together, organizations could focus on what part of the housing problem. There’s a nice section of the Times article that highlights how one organization changed its process:

Coordination meant that Ms. Costis’ group [SEARCH] could focus on case management, leaving job training, child care and other services to fellow continuum members. That, in turn, allowed it to avoid financial collapse and to hire more case managers, a critical need. “People were suddenly being housed with lightning speed,” Ms. Costis recalled. “It was a phenomenal difference.”

We see these partnership approaches in an international setting as well. Countries form trade agreements with each other in an effort to lower the cost of doing business internationally. Each country can devote more resources towards producing items they produce relatively cheaper than other countries. They trade those goods and services with each other and the result is increased production across the area.

The same has happened in Houston. Organizations spent the past decade devoting resources to services they perform better than others and the result has been an increase in housing for people desperately in need of it. In essence, they’re each increasing their production compared to before the arrangement. Houston was part of a group of 10 cities that received federal aid focused on “housing first” initiatives, but the other cities didn’t take the same approach as Houston. As a result, those other cities haven’t seen the same gains as Houston. Normally comparative advantage is heralded as a concept that can save people time and money, but in this instance, it’s also saving lives.

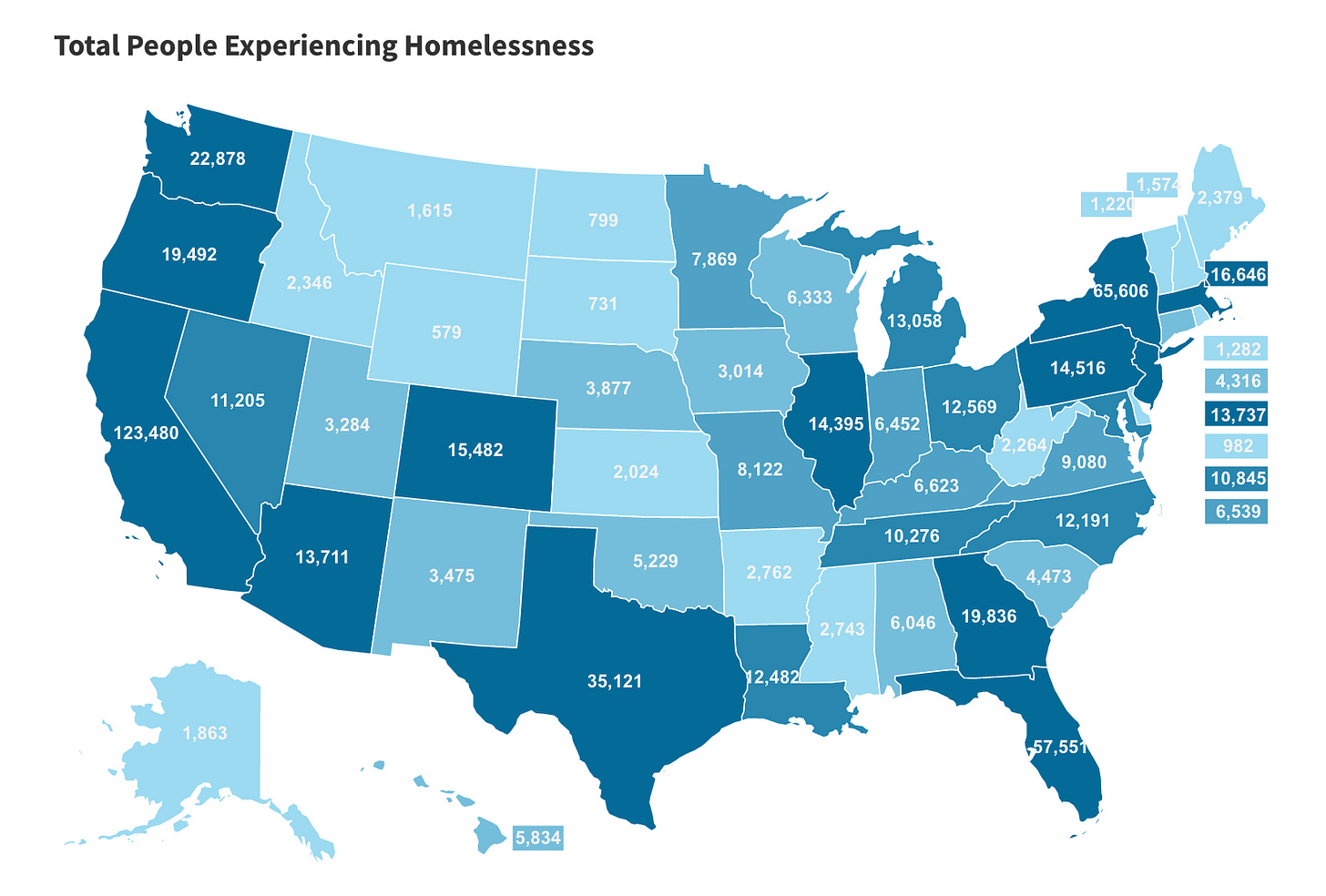

In January 2020, there were 580,466 people experiencing homelessness in America [National Alliance to End Homelessness]

One in every 14 Americans experiences homelessness at some point [New York Times]

Approximately 18% of all people experiencing homelessness were under the age of 18 [Housing and Urban Development]

Veterans make up about 6% of the US population, but 8% of the country’s homeless population. [Miltary Times]

Houston averages 99.6 days with high temperatures of at least 90°F [Visit Houston]

An estimated 19.6% of people in Houston live in poverty [US Census Bureau]