How Texas Instruments Won Math Class

The TI-84 hasn’t changed much since the early 2000s, but the reason it’s still around has more to do with economics than math.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Millions of students are back in the classroom. New notebooks, fresh pencils, maybe even a laptop upgrade. But for many, there’s also an old friend tagging along: the graphing calculator.

If you’ve taken a math class in the last 30 years, odds are you carried one around, too. Mine was a TI-83, and I can still remember my parents wincing at the $100 price tag. Adjusted for inflation, that’s close to $175 today.

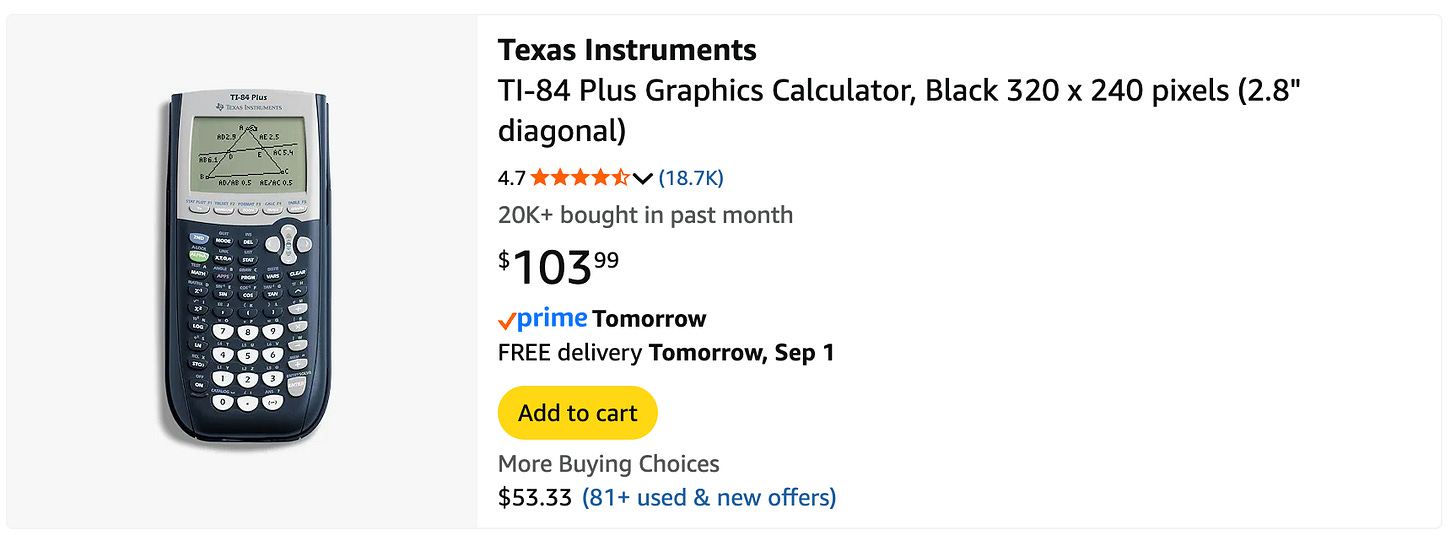

The funny part? That list price hasn’t really changed. Walk into a Target or Walmart today, and you’ll still see a TI-84 on the shelf for about the same price. They still graph equations, but some of the newer models can also run simulations and program in Python.

So how did this one company from Dallas manage to hold onto math class for decades? To answer that, we need to take a quick detour through its history.

From Semiconductors to Calculators

Texas Instruments wasn’t born as a calculator company. It started as a semiconductor firm, the kind of place that built the guts of computers and military systems. For a while, TI even made missiles, radar, and night-vision gear before selling off that side of the business to Raytheon in the 1990s.

So why get into calculators at all? Economists would call it an economy of scope: once you’re already making the chips, it’s cheaper to put them into other products too. In 1967, TI engineers did just that when they built the first handheld calculator. A few years later, they patented the first single-chip microcontroller, which packed the essential parts of a computer onto one piece of silicon.

That early patent gave TI a head start. By the time the TI-81 came out in 1992, school districts had already leaned into requiring calculators in math classrooms. Not long after, the College Board began allowing graphing calculators for the SAT and AP exams. Economies of scope can explain why TI got into calculators. But its technological superiority kept them near the top.

What Do We Mean by Market Power?

To be clear, Texas Instruments isn’t the only company making graphing calculators. Casio and HP also have their own models, and online tools like Desmos can graph just about anything for free. But when it comes to the classroom, TI is still the brand most people know. And that raises a question: if calculators are basically interchangeable, why hasn’t anyone unseated TI?

Economists study this kind of question under the heading of market power: the ability of a company to raise prices above competitive levels without losing all its customers. A pure monopoly, like a utility company in a small town, has the strongest form of market power. It’s the only option, so customers have nowhere else to go. Texas Instruments doesn’t have quite that level of control since it faces some competition from rivals.

But where does their market power come from? There are a few classic examples of where a firm’s market power comes from, like holding an important patent, controlling a scarce resource, or a giant retailer that uses its scale to push prices down. But none of those really explain why Texas Instruments has dominated math classrooms. So what does?

How TI Keeps Its Control

Remember when we said the College Board started allowing graphing calculators? That decision, covering the SAT and AP exams, was the hint to TI’s market power. Once a testing agency decides which devices are allowed, and then teachers start building lesson plans around those models, the market tips quickly in one direction.

TI helped that process along. They’ve long provided support to the College Board and sponsor a program called Teachers Teaching with Technology (T³) to train educators on their devices. The more teachers and test makers standardize on TI, the more students end up buying one.

That’s important because calculators themselves are basically interchangeable. Graphing a parabola on a Casio looks about the same as it does on a TI. But once a system is locked in, switching is costly. Not in dollars, but in time and effort. Teachers would have to rebuild their materials, and students would have to ask their parents to get them a second graphing calculator. Economists call this a switching cost: the friction that keeps people tied to a product even when alternatives exist.

TI may have gotten an early boost from patents and technology. But their staying power comes from the ecosystem of teachers, tests, and classrooms that reinforce the choice year after year.

Monopoly Outcomes (Sort Of)

The textbook monopoly story goes something like this: prices rise, output falls, and some people get shut out even though they’d be willing to pay more than it costs to make the product. Economists call that last part deadweight loss. It’s the slice of welfare that disappears when competition is limited.

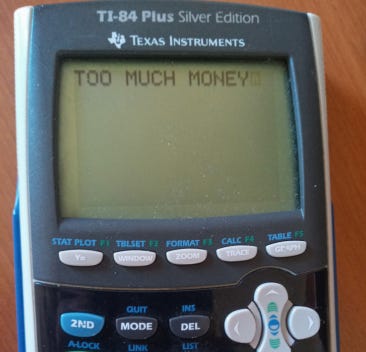

TI calculators fit some of that pattern. A hundred dollars is steep for a school supply. But unlike Apple, which unveils a sleeker iPhone every year, TI hasn’t needed flashy upgrades to keep sales going. The TI-84 Plus that debuted in the early 2000s looks and works almost exactly like the one you’ll find at Target today.

That doesn’t mean TI has the unchecked power of a pure monopoly. Casio and HP still sell alternatives, and math apps hover in the background. But because most students only ever buy one graphing calculator, TI has every reason to get them locked in early and keep them there.

Final Thoughts

The graphing calculator market shows how education can create its own pockets of market power. Once teachers, testing agencies, and students all converge on a single brand, the system reinforces itself.

That grip may not last forever. The College Board has recently started allowing a built-in Desmos calculator on the SAT and some AP exams. If teachers start updating their course materials around Desmos instead of a physical device, the foundation of TI’s dominance could begin to crack.

It wouldn’t be the first time calculators shook up the classroom. When they first appeared, many teachers resisted, worried they would erode basic math skills. Today, they’re impossible to imagine math class without. If Desmos pulls off the same trick, the next generation of students may not remember buying a TI at all.

Remember the friend who named their TI-84 graphing calculator? Send them this article. Or maybe just share it with any parent about to drop $100 on a calculator this fall.

Texas Instruments generated a net income of $4.8 billion for 2024 [Texas Instruments Inc.]

In 1986, the Connecticut School Board became the first to require a graphing calculator on state-mandated exams [The New York Times]

The first handheld calculator weighed 45 ounces and featured a small keyboard with 18 keys and a visual output that displayed up to 12 decimal digits [EdTech Magazine]

Texas Instruments accounted for 93% of the U.S. graphing calculator sales from July 2013 to June 2014 [The Washington Post]

Very timely as I just saw some TIs in Walmart, noticed the price, and in my head tried to calculate how much cheaper they are now in real terms relatively to the '90s.

And the youth absolutely cannot do calculations without calculators, or even with them sometimes. Just give a cashier with a computer screen dollars and coins such that your change should be something convenient like a single quarter and marvel at how your change is wrong every time (ex: give them $20.04 when the bill is $19.79 and you'll probably get $1 back after they stare in confusion for a minute).

"yOu WoN't AlWaYs HaVe A cAlCuLaToR iN yOuR pOcKeT" -- every math teacher when I was in high school

I still have my TI-83+, TI-89, and TI-89 Platinum from high school and College 1.0. Now that I'm back at College 2.0, there's pressure to get a TI Inspire CAS which has a bunch of new (and, admittedly, quite useful) features. But it's $170 and comes with a steep learning curve. The flagship offerings from HP, et al, are comparable if not superior, but that makes the learning curve even steeper. Fine at work, perhaps, but not something you want to be figuring out on an exam.