The Economics of "Girl Math"

It sounds a lot like a lesson in behavioral economics

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

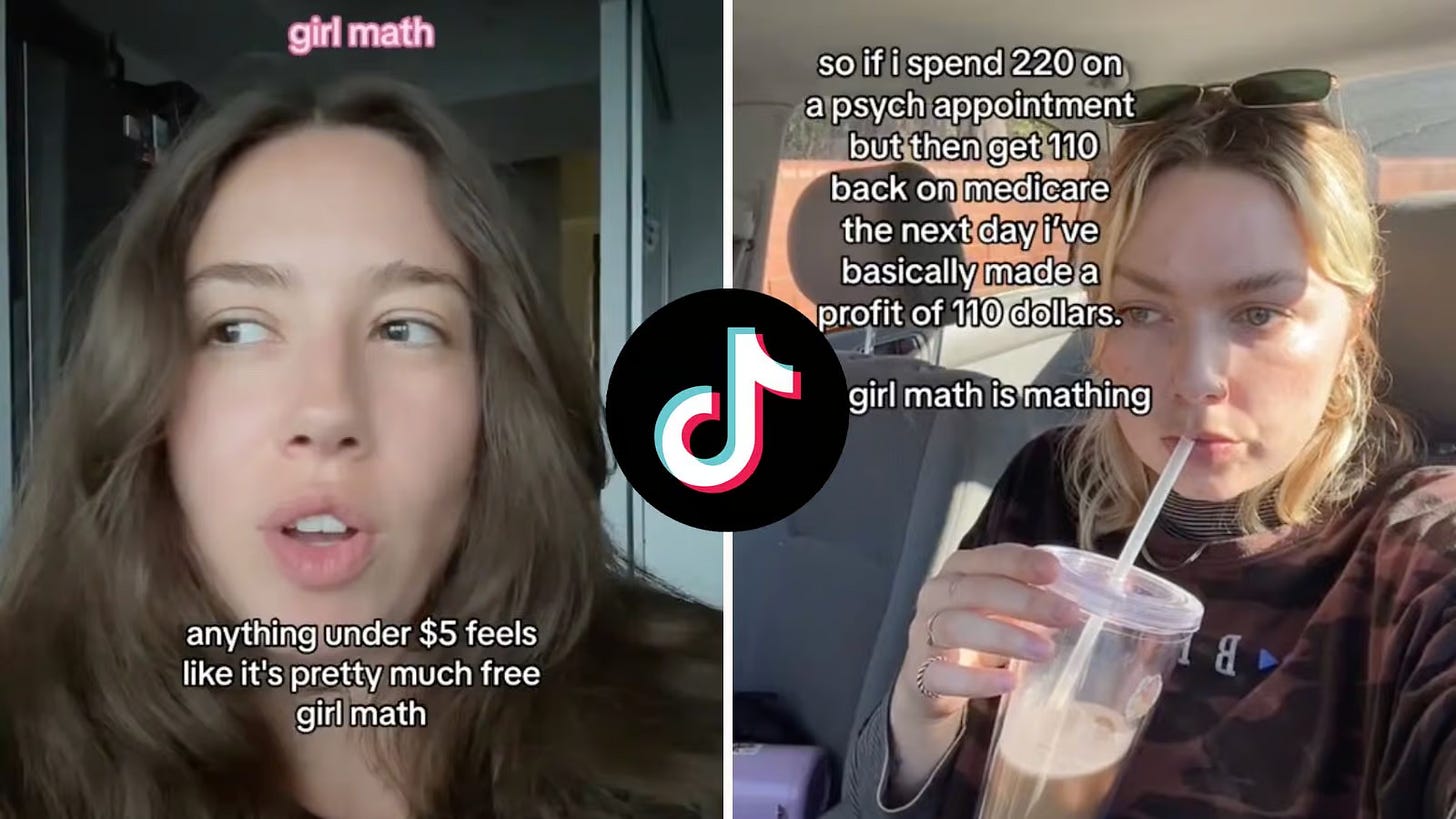

If you’ve been scrolling through social media lately or have a young adult in your household, you might have caught wind of a viral trend that’s taking the internet by storm. I’m talking about “girl math,” a quirky blend of creative rationalization and financial justifications that’s turning the tables on how some people perceive extravagant purchases while trying not to deviate too far from common personal finance advice.

So, what exactly is “girl math”? It’s more than just crunching numbers; it’s a mindset that’s all about making luxury purchases feel reasonable. Imagine seeing a new $400 designer handbag in the store. Sure, the price tag might initially make you uncomfortable, but “girl math” steps in and breaks it down into bite-sized pieces. It’s the art of calculating the cost per use. Suddenly, that seemingly outrageous splurge translates into a mere $1.10 per day. That’s a bargain and an example of mental accounting!

But where did this trend originate, and why has it captured our attention? It all started from a somewhat unflattering perspective on women and their finances. Yet, thanks to the magic of TikTok, that story is being rewritten. Social media has started to embrace “girl math” and redefine it as a careful dance between economics and psychology. In other words, “girl math” is just behavioral economics.

Before we get into examples, where did the magic behind “girl math” get its roots? Meet Richard Thaler, the captain of the behavioral economics ship. Thaler is a household name among economists, and he rightfully earned a Nobel Prize for his work on figuring out how our brains interact with money and decisions.

The lesson from behavioral economics is that people only save if it’s automatic.

We’re all perceptible to mental biases, but “girl math” highlights some of them in a fun and self-deprecating way. Here are a few other biases that have popped up with “girl math.”

Framing and Anchoring: Sales Prices

Let’s start with an easy bias that we’ve likely all fallen for the most often. Think about those magical sale prices. You know, the ones that seem too good to resist. “Girl math” involves separating the discount from the original price, treating the difference as “found money.” Retailers skillfully rely on framing by highlighting discounts and anchoring the original price in consumers’ minds.

We’re all so guilty of this bias that when a popular department store tried to remove its sales and just offer low prices, it ended up being a marketing disaster. When we see an item marked down from its original price, we’re anchored to the initial price tag, and retailers have made us feel like we’re getting a steal. In the context of “girl math,” the discount is now seen as “extra” money that can be allocated toward other luxury purchases rather than moving to a savings account.

Sunk Cost: Getting a Refund is Just Like Free Money

Imagine you've splurged $40 on a sundress. You bring it home and realize you don’t love it that much. You’re faced with a choice – return it or keep it? You don’t love it, so you head to the store to get your $40 back. Why do you suddenly feel richer? It’s a twist on the classic sunk cost concept.

Sunk costs are normally ones that are lost forever, “girl math” flips the script. You got your $40 back, so an economist wouldn’t call that a sunk cost. If you’re using “girl math,” the money you spent is sunk, and returning the dress means that whatever you buy with that $40 is basically free. It’s a clever way of using the concept of sunk cost as a justification for guilt-free shopping.

The Pain of Payment: Cash vs. Credit

Ever noticed how payment methods affect how you feel about spending? When you hand over cold, hard cash, you feel the "pain of payment" acutely. It’s like an emotional punch in the gut that makes you reconsider. This emotional reaction is what "girl math" leverages – choosing payment methods that distance us from this pain, like deferred payments or electronic transactions, allowing us to indulge without the sting.

Buy Now, Pay (More) Later

Back-to-school shopping can get expensive quickly and recent inflationary pressure hasn’t helped. The second half of the summer is a large enough shopping event around the United States that the National Retail Federation ranks it among its top spending events along with the winter holidays

Present Bias: Rationalizing Luxury

What about treating ourselves? The rise of "treat" culture on TikTok pairs perfectly with "girl math." It’s about spending as a form of self-care during tough economic times. It’s that instant gratification, the present bias, that nudges us toward treating ourselves. TikTok user @izzybelle1123 explains her method as a tax:

I have a thing called drink tax, anytime I go somewhere I have to get something to drink

Sure, it may be better to store some of that away in a savings account and enjoy more money in the future, but "girl math" becomes a tool for justifying luxury as self-care, prioritizing our emotional well-being over long-term finances. It’s just one small way to escape all the other stuff going on in the world right now.

“Girl Math” in a Nutshell

So, there you have it. The economics of “girl math.” It’s a mix of mental accounting, framing, and anchoring, all wrapped up with a touch of present bias. From cost per wear to sale discounts and the psychology of payments, “girl math” teaches us a valuable lesson – how we justify our spending and how we handle our finances can have a profound impact on our mental well-being.

It’s a quirky approach to embracing life’s indulgences, a bit like turning dessert into a rationale you can enjoy guilt-free. As you consider your next splurge or weigh the thrill of a sale, remember: sometimes, it’s okay to give yourself a little treat. “Girl math” is a reminder that, in moderation, little luxuries can add a splash of joy to our lives.

Of the estimated 333,287,557 people living in the United States, 50.4% of them identify as female [U.S. Census]

Based on data from the 2017-2018 school year, 42.4% of undergraduate math degrees were awarded to female students [National Center for Education Statistics]

According to data from TransUnion, credit card users between the ages of 18 and 29 have around $2,900 of debt [CNBC]

When JCPenney eliminated coupons in favor of an “everyday low price,” they reported a $163 million loss in the first 90 days of the year [Forbes]

An estimated 41% of Americans say none of their purchases in a typical week are paid for using cash [Pew Research Center]

I don't know whether to be offended that this reinforces a stereotype of women as hopelessly incapable of managing their finances or saddened by the mass appeal of this 1980s-like materialism. I agree with the sentiment that treating yourself now and then is a valid use of resources, but the clips posted here (admittedly a very small sample size) are hopefully not the guiding force behind decision making these days. If they are, then at least there won't be a recession anytime soon. Consumers will just keep spending until there isn't anything left to spend, then they will just put it on the card. However, due to the economic principle of tradeoffs, their handbags will have to be sold (maybe as 2020s retro) to fund the retirement they didn't save for. Will girl math save them when at 85 they are still working? "You see, I took out a reverse mortgage on my handbag and paid off the credit card so now I have free money."