Why We Say We'll Cancel But Never Do

Earlier surveys found 23% of Disney+ subscribers would change their subscription if prices increased 38%, but only 6% actually did. Why do people behave differently than how they say they would?

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

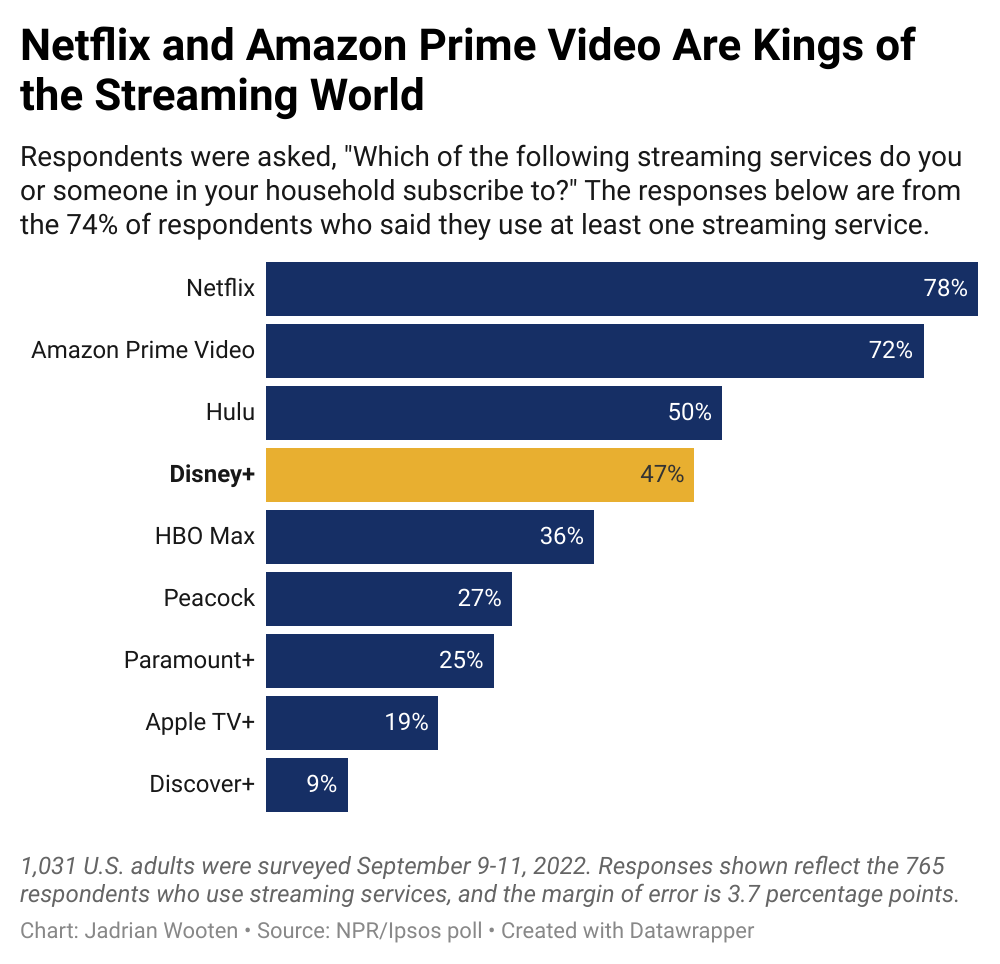

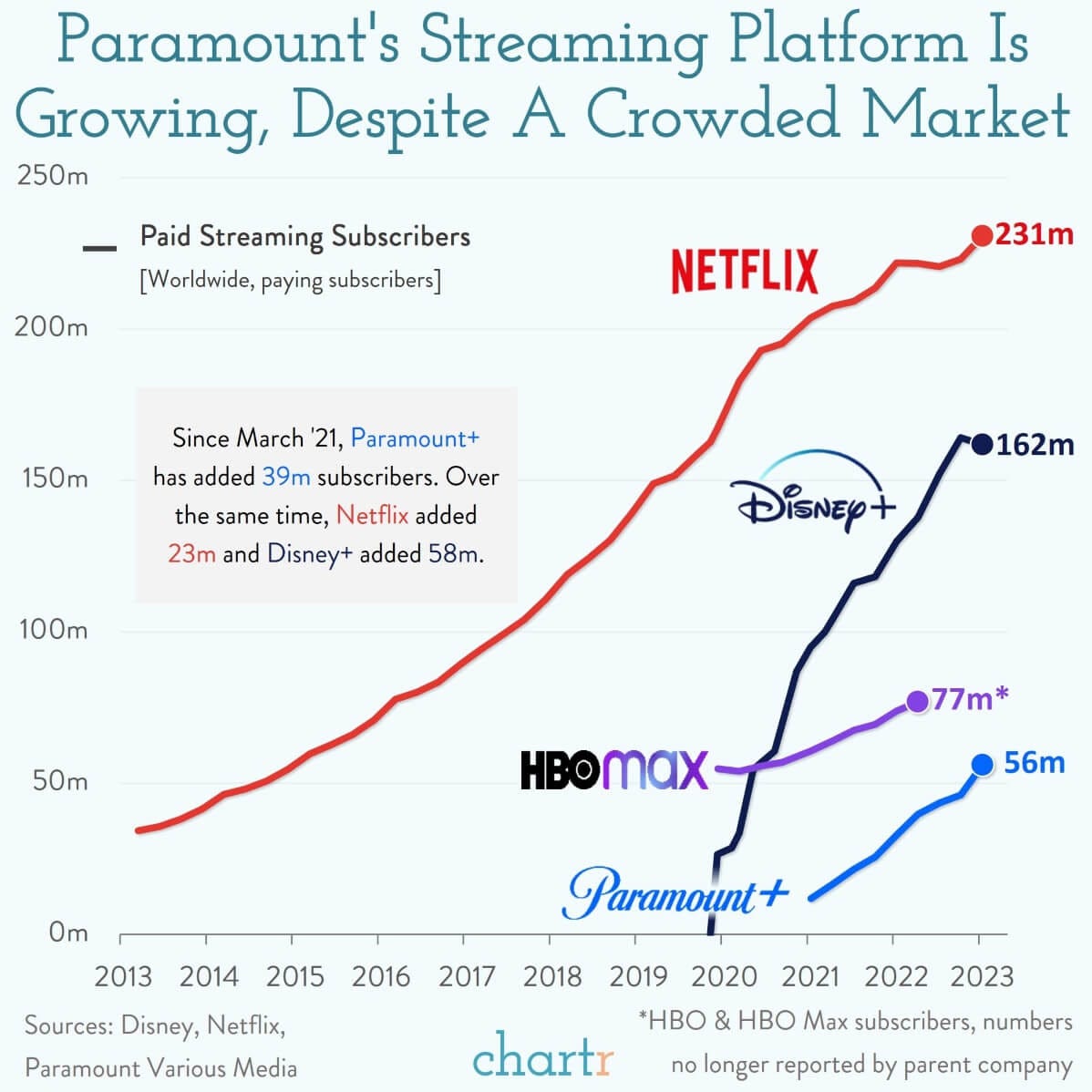

Last summer Disney announced that it would be raising the price of the ad-free version of its streaming platform, Disney+, by $3 at the end of 2022. A recent survey found that Disney retained 94% of its ad-free Disney+ customers despite raising the price by 38%! When the price increase was announced last summer, surveys found that around 23% of those asked would opt for the cheaper ad-supported plan instead. This raises an interesting question: why do people behave differently than how they say they would behave? The answer lies in the economic concepts of stated and revealed preferences.

Stated preferences refer to what people say they would do in a given situation, while revealed preferences refer to what people actually do. In the case of the price increases for the ad-free version of Disney+, the earlier surveys reported behaviors of what people stated they would do once the price increased. The fact that the vast majority of customers stayed with the ad-free version of the service after the price increase shows that their revealed preferences were quite different.

There are several reasons why stated and revealed preferences may differ. One reason is that people may not be fully aware of their preferences or may not want to reveal their true preferences due to social desirability bias. In the case of Disney+, customers may have overestimated their willingness to switch to a different platform or the ad-based option. They may have felt embarrassed to admit that they were willing to pay the higher price when most surveys like this often expect people to stop paying for products when prices increase.

It’s also possible that people differ in their stated behavior because of limited information. A customer may have stated that they planned to switch to the cheaper, ad-supported version of Disney+ when prices increased because they may not have felt satisfied with the selection of movies and TV shows. They may not have fully explored all of the options available on the platform at the time of the survey, but after the survey, they may have invested more time in looking through the available content and realized that it contained more shows than they originally thought. Armed with the additional information, they decided to stick with their ad-free version of the site.

Another possibility is that customers may have overestimated how much they value lower prices relative to the other benefits of an ad-free Disney+ experience. For example, many customers may enjoy the exclusive content that Disney+ offers, such as Marvel movies and Star Wars series, without having ads occasionally interrupt their show. When confronted with news of price increases, they may have initially believed they wouldn’t have the ad-free option worth the additional price increase. As time goes on after the survey, people may have been more consciously aware of how much they enjoyed the ad-free experience and decided it was worth the additional few dollars.

Lastly, it’s also possible that people are just simply oversubscribed and didn’t notice the price increase among all of their other subscriptions. About 7-in-10 people autopay for their monthly subscriptions, which makes it easy to forget about price changes. This can be especially true when the service in question makes up such a small share of a family’s overall spending in any given month.

Stated and revealed preferences are closely connected to the concept of elasticities in economics, and this is a neat opportunity to also talk about that! Elasticity is a measure of how responsive consumers are to changes in factors (like price) that affect the quantity demand for a product. We can actually use the most recent survey data to estimate the degree to which Disney+ customers are sensitive to price changes. If a product is highly elastic, small changes in the price will result in a relatively significant change in the quantity demanded. On the other hand, if the price changes for an inelastic product, it will have a relatively small effect on the quantity demanded.

In the case of Disney+, the company raised its prices by 38%, but only 6% of customers actually canceled their ad-free subscriptions. This suggests that the price elasticity of demand for Disney+ is relatively low, meaning that customers are not very responsive to changes in prices. Based on this inelastic response, Disney may have room to raise prices again, which the company's CEO has already hinted at earlier this month. We’ll have to wait and see if Mr. Iger’s stated preference of wanting to raise prices lines up with what he’ll actually do in the coming months.

Disney launched Disney+ in 2019 at a price of $6.99 a month [The Wall Street Journal]

Disney+ has an estimated 161.8 million subscribers as of February 2023 [Variety]

Fully 92% of Netflix non-users and 90% of Disney+ non-users said they watched ad-supported streamers [Insider]

The premium bundle of Hulu with live TV along with Disney+ and Hulu without ads is priced at $82.99 per month in the U.S. [CNBC]

For the full fiscal year 2022, Disney’s Direct to Consumer division (Disney+, Hulu, and ESPN+) lost Disney $4 billion total [The Walt Disney Company]

It’s strange to think maybe they’ve priced on the inelastic part of demand in the first place. Which I’m assuming is the case if they can raise price 38% without losses.