Behavioral Economics Can Explain the Challenges of Online Dating

Despite the popularity of online dating, why is finding "the one" still a challenge for so many people?

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 3,900 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

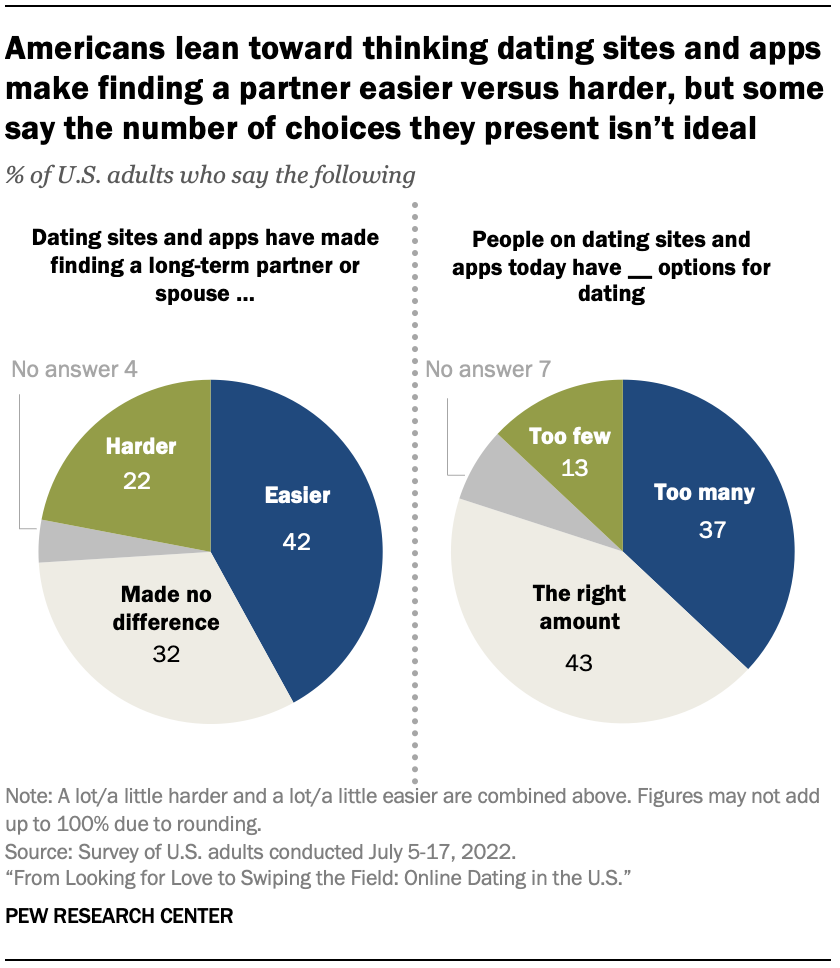

Online dating platforms promised a revolution in romance. They were supposed to lower the cost of finding a romantic partner, making it easier and less time-consuming by connecting users to a wider pool of potential mates. Lower transaction costs are typically a good thing. The idea was simple: break free from geographic constraints and match with someone who shares your interests and preferences.

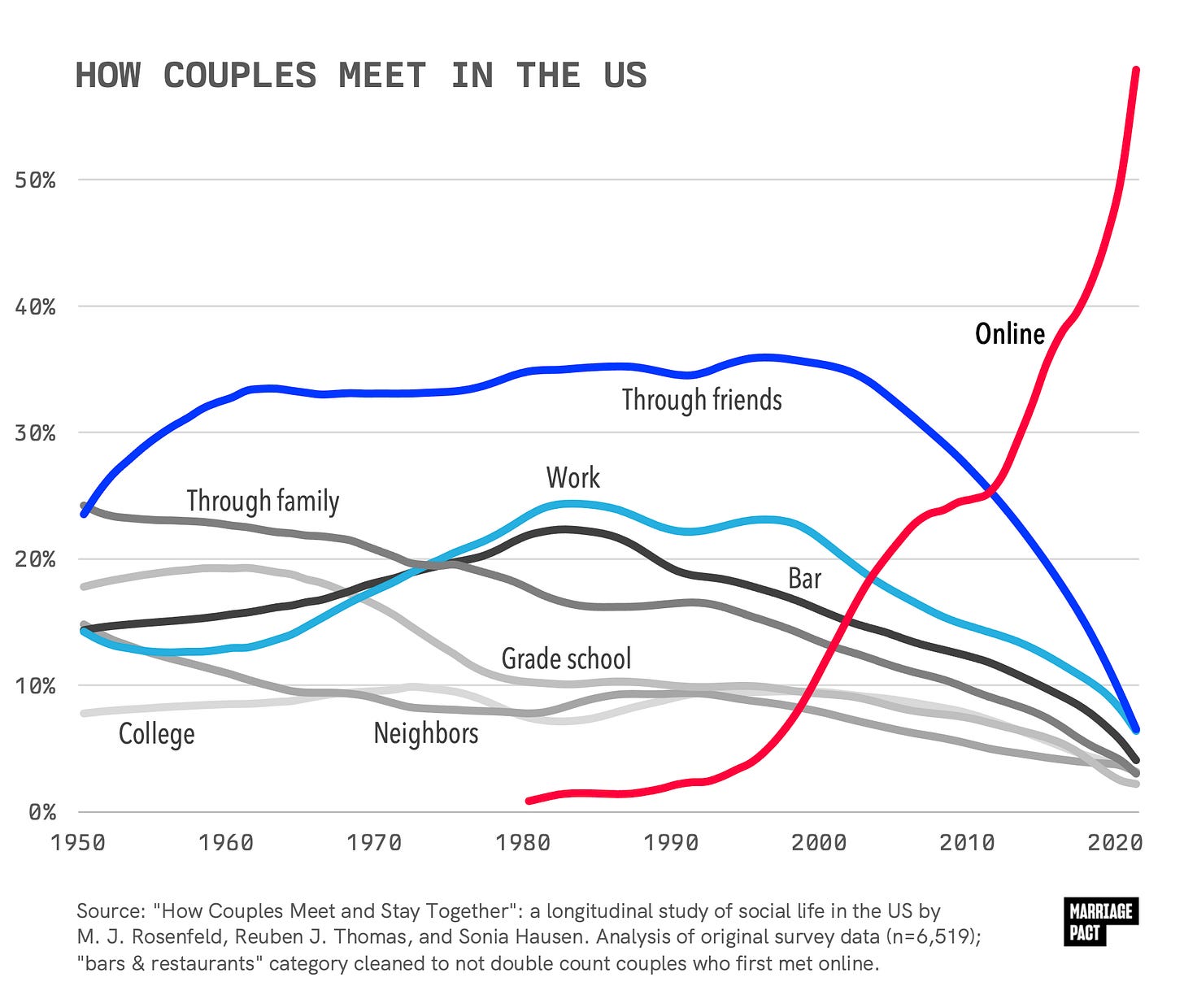

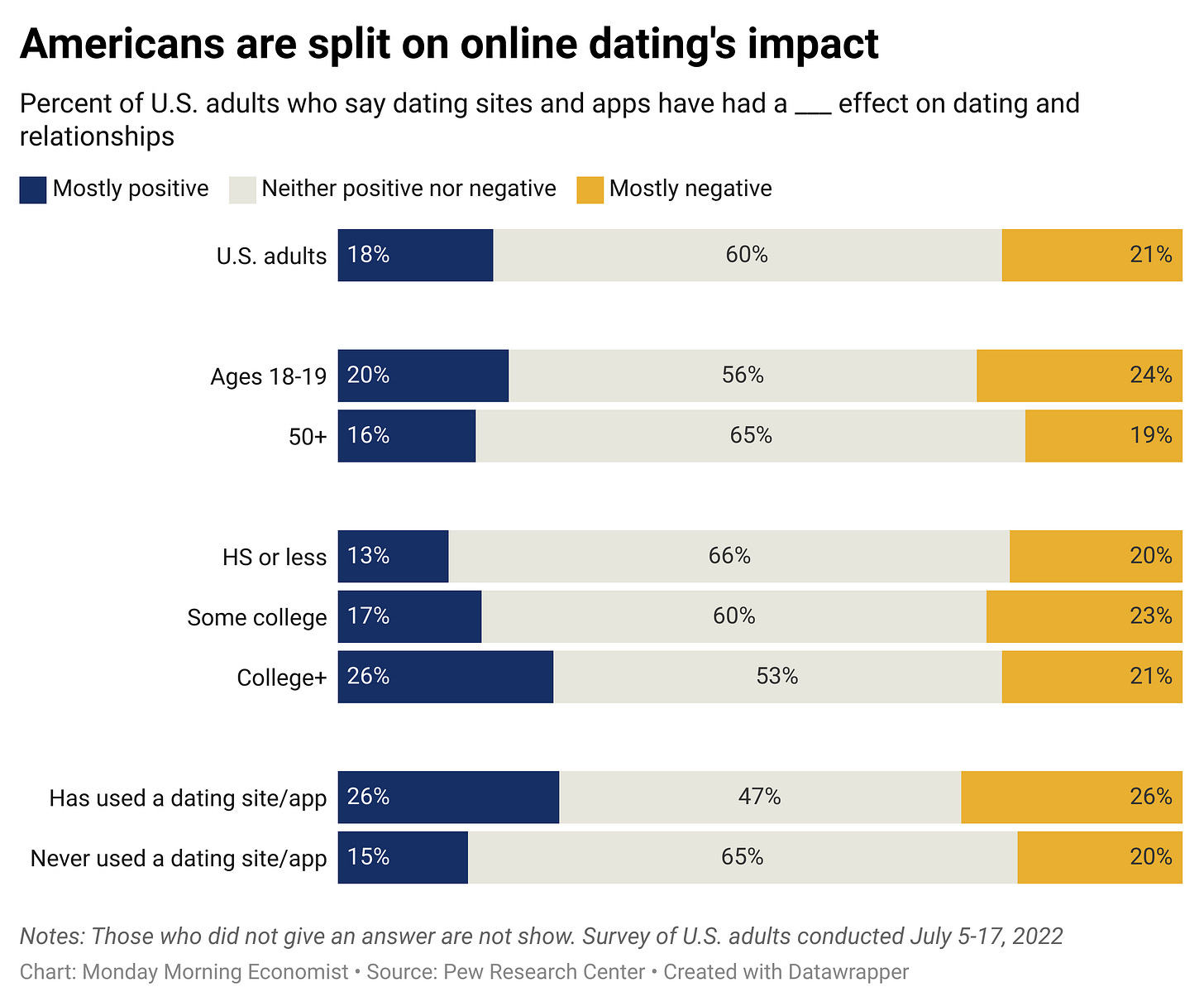

Despite the convenience of endless swiping, going from swiping to a meaningful relationship is fraught with economic pitfalls. Yes, you read that right—economic pitfalls, like adverse selection and the paradox of choice, are getting in the way of you finding true love on a dating app. A lot of couples are meeting on dating apps instead of through friends, but a whole lot of single people are having a hard time turning those online matches into a relationship IRL.

Matching Markets are Different

Let’s unpack by starting with the concept of matching markets. In a traditional supply and demand model, prices adjust until they find a sweet spot that satisfies buyers and sellers. Matching markets are a bit different. Instead of prices calling the shots, it’s all about preferences and finding the perfect fit. The goal is to find a compatible match, not the highest bidder.

When it comes to matching markets, economists are big fans of what they call "thick markets." Why? Because the more people you have participating, the better the chances are of everyone finding their ideal match. It’s why finding “the one” in a small town can be challenging. Dating apps pull together a massive collection of profiles, all in the hopes of making these markets as thick as possible, thereby maximizing everyone’s chances of finding that perfect match.

Matching markets aren’t just about dating; they play a role in diverse areas, including organ donations and job placements. However, things get complex when we apply the logic of matching markets to finding love. On the surface, pairing up with someone who has the same level of education or the same high credit score as you might seem ideal. This concept, called assortive mating, comes with its own set of problems. While you and your partner might bond over indie movies or artisanal coffee, this type of matching can unintentionally contribute to wider economic issues, like increasing income inequality and making it harder for people to move up the social ladder. This, in turn, can lead to a society that’s more divided by wealth and education levels.

If thick markets and assortive mating were the whole story, finding a match should be a breeze. But as many swipers can attest, reality begs to differ. This is where behavioral economics comes into play, offering explanations for why too much choice can be a bad thing. While there are mechanisms in place to streamline the matching process, they also introduce complexities that challenge our ability to make decisions.

Culprit #1: The Overchoice Problem

First up is the paradox of choice. The theory suggests that while having options is great, too many can overwhelm us, and lead to indecision and dissatisfaction. Dating apps present an illusion of limitless choices, especially in bigger cities. This can tempt users into a cycle of endlessly seeking someone marginally better. This abundance of options can then result in a paradox where making a meaningful connection becomes surprisingly elusive. Despite the thrill of matching with someone, both know that there’s always another possibility just one more swipe away.

It’s a recipe for commitment-phobia and relationship dissatisfaction. The abundance of options leads to “choice paralysis,” and it feels better to just not choose at all. To fight that paralysis, you may go on multiple first dates with all sorts of people but never follow up because you can’t decide which person you want to pursue. First dates are now held to a much higher standard. A single imperfect may be enough to call it quits since you know that there are more matches just waiting for you if you swipe right a few more times.

Culprit #2: Adverse Selection in the Dating Pool

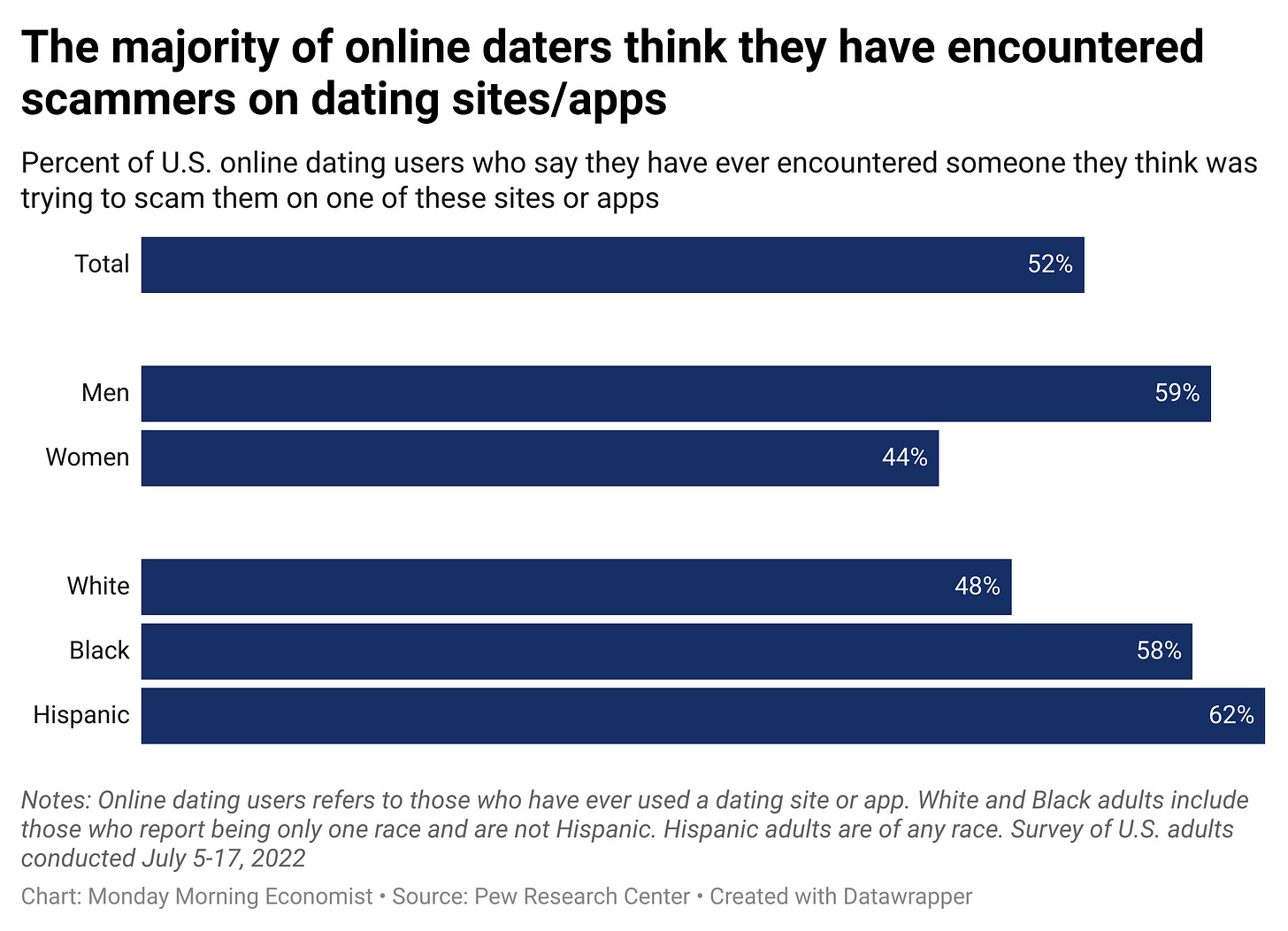

Speaking of those imperfections, there’s also an adverse selection problem in dating markets. We often see this issue pop up more in insurance markets, but it’s just as relevant in the dating world. It refers to the scenario where the presence of information asymmetry leads to the market being flooded with "lemons" — a term borrowed from economist George Akerlof’s analysis of the used-car market.

In dating terms, overly curated profiles promise more than they can deliver. This mismatch in expectations can discourage genuinely good matches from sticking around, leaving the market flooded with less desirable options. As the high-quality matches log off the app, the only people left are matches that are less likely to result in successful relationships.

Tinder’s introduction of a $500 subscription fee for its Tinder Select tier is a noteworthy example of a firm trying to solve the adverse selection problem. This ultra-premium service is aimed at less than 1% of its user base, Specifically, it’s intended for the most active and presumably high-quality potential matches. The service promises exclusive features that enhance search and matching capabilities.

By gating these advanced options behind a substantial fee, Tinder is effectively creating another market that is designed to attract and retain users who are serious about finding meaningful connections, thereby addressing the adverse selection dilemma. The hope is that the high price tag will differentiate genuine profiles from those contributing to the flood of less desirable matches.

Navigating the Marketplace

So, how can you navigate this complex matching market? Understanding the role that the paradox of choice and adverse selection play in the market is a good start, but it also helps to adjust your strategy to account for these concepts before you get started. Narrow your focus, be authentic, and remember that the algorithm won’t do all the work for you. Just like our economy, the search for love is full of unpredictability and hidden variables. While these platforms have the potential to connect us in ways never before possible, the path to true love still requires human interaction.

Nearly 47% of the U.S. population (just over 117 million people) are currently single [U.S. Census Bureau]

47% of Americans say dating is harder now than it was 10 years ago [Pew Research Center [Pew Research Center]

About half of those who have used dating sites and apps (52%) say they have come across someone they think was trying to scam them [Pew Research Center]

Individuals between ages 43 and 58 found the most success with online dating, with 72% stating that meeting on a dating app led to a romantic relationship [Forbes]

A cross-sectional study of 475 people over the age of 18 found that those who used swipe-based dating apps experienced significantly higher rates of psychological distress, anxiety, and depression [BMC Psychology]

The $500 fee also seems like it may act as a wealth signal - further enhancing associative matching.