Making a Match

A look at Al Roth's work on matching markets and the economics behind organ transplants

The world of organ donations is complex and highly regulated, but it is also ripe for economic analysis. Last week, the federal government outlined a plan to revamp the nation's organ transplant system. There are a number of economic concepts at play, but one of the most important is the concept of matching. Matching is crucial when it comes to organ donations because it ensures that the right donor is matched with the right recipient, which in turn maximizes the chances of a successful transplant.

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a nonprofit organization located in Richmond, Virginia, has been managing the country's organ transplant system since 1986, after being awarded the first federal contract. As a monopoly, UNOS has been the sole organization overseeing the distribution of donated organs to critically ill patients. The federal government plans to transfer some of those responsibilities to other external organizations because the nation's organ transplant system has been plagued by problems including damaged or discarded organs and long wait times. This plan includes a focus on improving the matching process, and this is where economics comes in.

One of the key figures in this area of economics is Al Roth, a Nobel laureate and a pioneer in the field of matching markets. These are markets in which prices do not necessarily dictate the allocation of goods or services. In a commodity market, sellers may not necessarily care who buys their products. For matching markets, both buyers and sellers must be willing to accept the other party in order for a transaction to occur. Examples of matching markets include job markets and college enrollment. Roth's work has been instrumental in improving the matching process in areas like this, but he is perhaps most famous for his role in improving the market for organ donations.

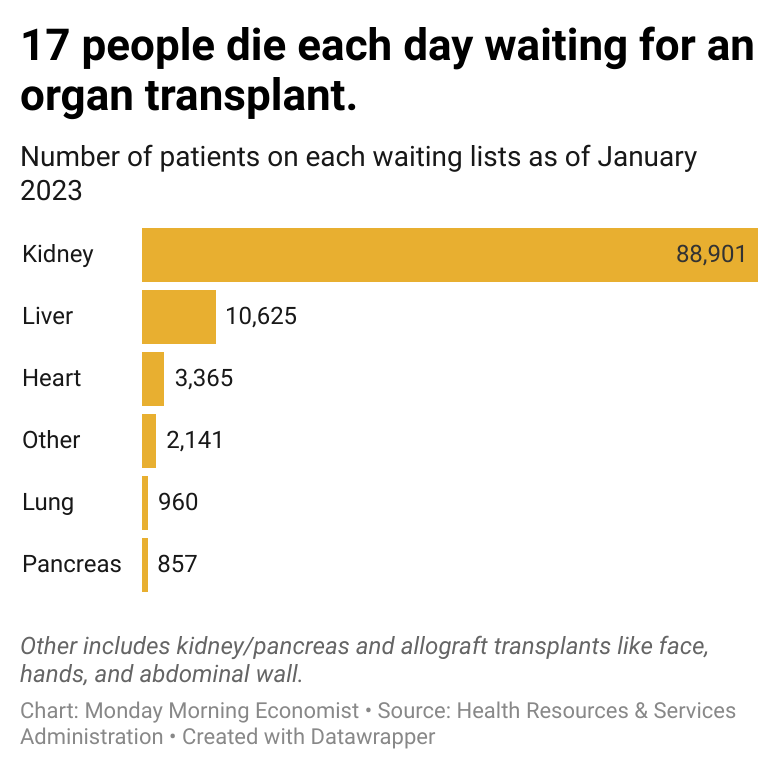

The problem with organ donations is that there is a limited supply of organs available, but a high demand for them. The shortage is further compounded by the illegality of paying donors and the challenge of finding compatible donors. For instance, kidney transplants require a match in blood and tissue type, making it difficult to find a suitable donor for each recipient. Consequently, this shortage leads to 17 deaths daily among people waiting for organ transplants.

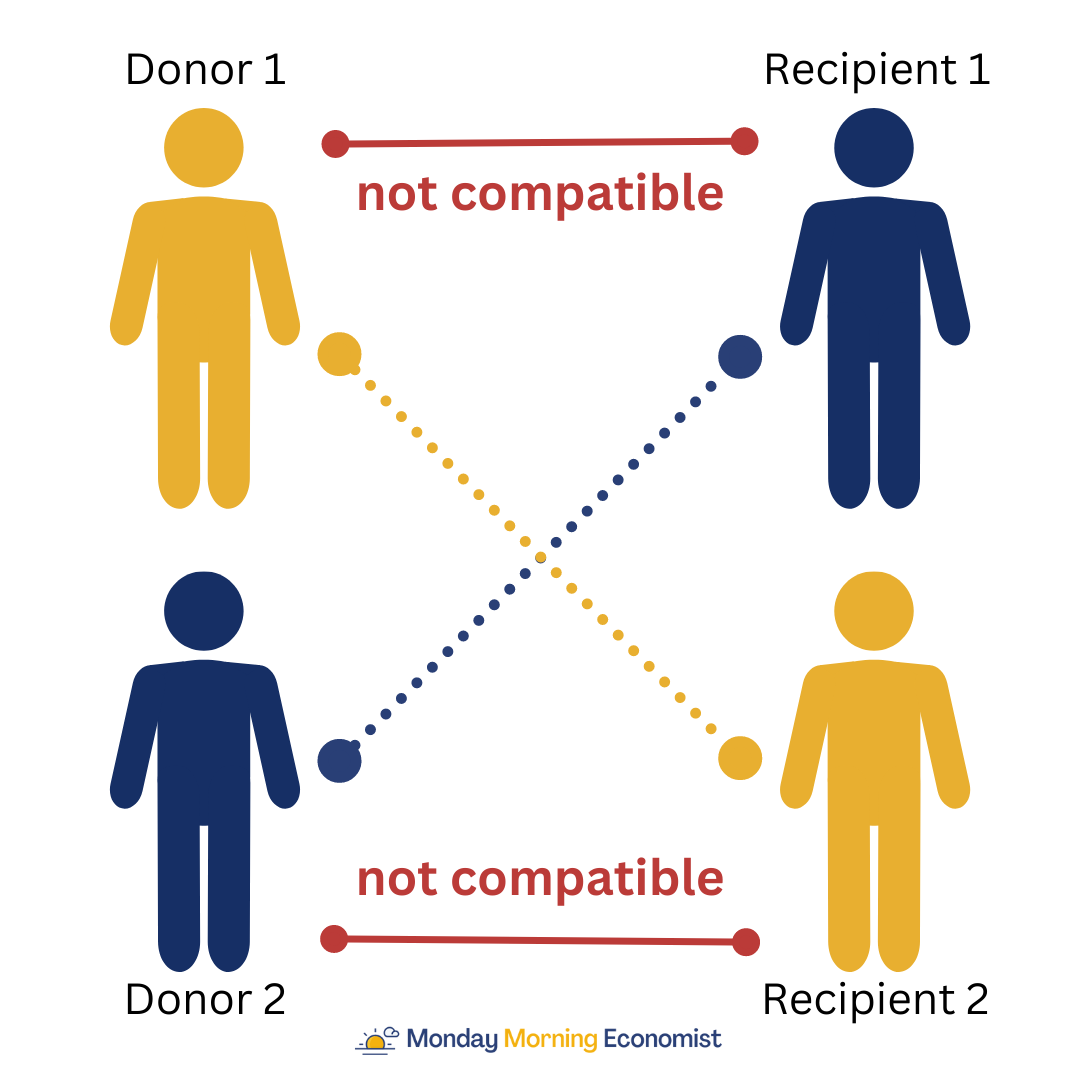

This is where matching markets come in to help alleviate some of the issues. Roth's early work focused on developing algorithms and mechanisms that improve the matching process in organ donations, particularly among incompatible donor-recipient pairs. One of his key contributions has been the development of the kidney exchange program.

The kidney exchange program is a system in which incompatible donor-recipient pairs are matched with other pairs so that each recipient receives a kidney from a compatible donor. For example, if a donor is not compatible with their intended recipient, but is compatible with another recipient, and that recipient's donor is compatible with the first recipient, a match can be made.

This system is based on the idea of a "chain" of transplants, in which a donor donates a kidney to a recipient, but their intended recipient is not compatible. Instead, that recipient receives a kidney from another donor, whose intended recipient is also not compatible. This chain can continue indefinitely, with each recipient receiving a kidney from a compatible donor. This system has been highly successful in improving the matching process for kidney transplants.

The economics of organ donations also highlights the importance of incentives. Incentives can be used to encourage people to donate their organs and to ensure that the organs are used effectively. For example, in some countries, people are automatically enrolled as organ donors unless they opt-out. In other countries, donors may receive compensation for their donation, such as payment for time off work or reimbursement for travel expenses. However, incentives can also lead to ethical dilemmas. For example, if donors are compensated financially, there is a risk that they may be coerced into donating, or that the compensation may create a market for organs, which raises questions about the commodification of the human body.

The role of economics in organ donations is a vital one. Matching markets and incentives are key concepts that can help to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the organ transplant system. Alvin Roth's work on matching markets has been instrumental in improving the matching process for kidney transplants, and his research has also shown promise in other areas of organ donations. The federal government's plan to revamp the organ transplant system is a step in the right direction, and it is important that we continue to explore innovative solutions to address the challenges facing the organ donation system.

Around 104,000 people in the United States are on the waiting list for an organ transplant [Health Resources and Services Administration]

Every 9 minutes, another name is added to the waiting list for an organ [Penn Medicine]

About 95% of U.S. adults surveyed say they support organ donations, yet only 58% actually sign up to become donors [UC Irvine Health]

More than 42,800 organ transplants were performed in 2022 [Health Resources and Services Administration]