September Is Not the Most Wonderful Time of the Year

The winter holidays are still a few months away, but that's not stopping some stores from putting out there Christmas selections early. Game theory can help us understand this pre-emptive behavior.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

While browsing Barnes & Noble over the weekend, I noticed an employee setting up their holiday card collection in the front of the store. This seemed really odd to me because there are still a few days left in September and there are still two major holidays on the calendar before the winter holidays roll around. Could there possibly be an economic explanation for why Christmas decorations and sales are creeping into September?

At first, I thought this was just a fluke. Maybe Barnes & Noble was getting a head start on the holiday season because they were worried about supply chain issues. Last year did include a variety of shortages from popular toys to Santa Claus himself. Reports over the summer indicated that supply chain disruptions have come for the paper industry and maybe the store is bracing for that by spreading out card sales over an additional month.

I decided to make a quick stop at Target across the street, but my fear that Barnes & Noble was simply an outlier isn’t holding up on my investigative journey. It appears Target has also joined in on the Christmas creep and put out some holiday toys on their endcaps:

One possible explanation for such behavior is that retailers believe shoppers are increasing their demand earlier than in previous years. Articles on holiday shopping advice started popping up last year in the first week of October. While Black Friday is often seen as the start of the holiday season, some stores started posting their Black Friday deals much earlier to avoid crowded stores in the midst of the pandemic.

Other articles at the time suggested customers should shop early to increase the likelihood of obtaining items that had been impacted by supply chain disruptions. While those reasons could explain Christmas creep in 2021, it’s hard to see why those same reasons would affect the holiday season in 2022. Heck, Walmart announced its “Top Toy List” at the end of August this year!

Maybe economics can explain this behavior? The ever-earlier Christmas season could help those responsible for maintaining the already shaky supply chain. Spreading out consumption over multiple months means distributors aren’t rushed to get products to retailers in a narrow 4-week window. However, an extended Christmas season is a mixed bag for store owners.

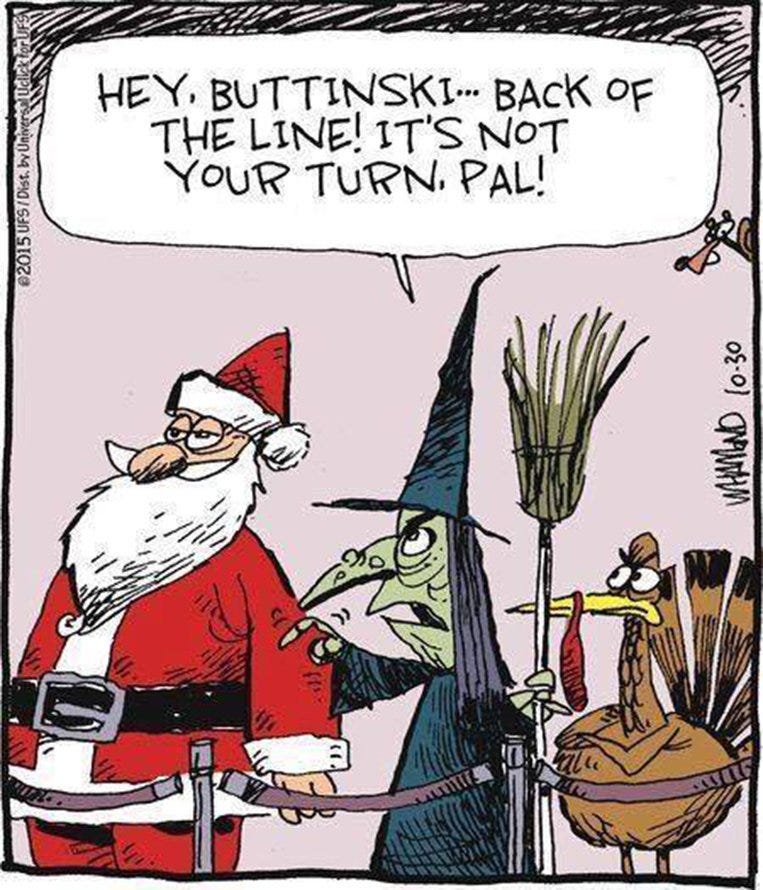

While it may benefit some stores, those benefits are likely to come at a cost to competitors who wait a few extra days to set up their displays. If it was beneficial to set up displays a few days earlier last year, then competing stores realize they need to start even earlier to beat their competitors. This process repeats itself and now stores are setting up holiday displays months before the season begins. It looks like Charlie Brown writers were on to something when they realized it’s only a matter of time before we start seeing Christmas decorations in the middle of Easter:

Game theorists commonly study this sort of interdependent behavior. While it may benefit society for stores to wait until after Thanksgiving, there is an individual incentive for store owners to put out their decorations one day earlier than their competitors. When a store decides to do this, it impacts its sales and also its competitors’ sales. As each retailer realizes the individual benefits and begins to act on their own individual incentives, the “starting day” for holiday decorations creeps earlier and we’re all worse off.

One of the many reasons that the holiday season is so special is because it occurs during a particular time of the year. The longer the holiday season stretches out, the less special the season becomes as consumers begin experiencing diminishing returns. People still need to get through their Pumpkin Spice Lattes before they can start thinking about where to hang the mistletoe. If you’re annoyed by early markings of the winter holiday season, you’re not alone:

Unfortunately, being an early mover can be beneficial when there is a first mover advantage. When stores set up their displays a day early, they capture some additional revenue from shoppers who are willing to start shopping a bit earlier. Same-store sales is a metric that retail firms use to evaluate the performance of their individual stores. If it was beneficial to put out the display earlier than normal last year, then stores will do it again this year. For stores that saw their sales drop and believe it was because their competitors started earlier, they may decide to set up even earlier to avoid being left behind.

Game theorists call this particular interdependent situation a war of attrition. Players are fighting for the same prize, but spend an increasing amount in order to be the “winner” of that prize. In this game, the prize is that cherished holiday spending category, which is the largest shopping event on the US calendar. The costs for the firm come from setting up displays earlier each year. A war of attrition has its roots in military combat, but a popular (and less violent) example can be seen in the dollar auction game. This episode of Brain Games recreated the auction using a $20 bill:

So wouldn’t this outcome suggest that the process repeats itself every year until the holiday season begins in January? That would be the case unless some companies were hyper-rational and recognized the game as a war of attrition. Players who recognize the design of the game can quit early enough to avoid suffering losses. Since this is a repeated game that’s played every year, those players know enough to not start playing the game next time around. Some companies, like Nordstoms, purposely refrain from decorating their stores until after Thanksgiving. Others, like REI and Patagonia, don’t even participate in Black Friday sales. They’ve recognized that the costs of letting the holiday season creep into October aren’t worth the potential gains.

For the rest of us, the best we can do is refrain from participating. The reason stores have an incentive to start earlier is that there are shoppers willing to purchase items earlier. The best we can do is try to ignore it until you walk into your favorite store and realize It’s Suddenly Christmas:

There were an estimated 1.3 billion Christmas cards sold in 2020 [Greeting Card Association]

During the Christmas season, almost 28 LEGO sets are sold each second [National Geographic]

Nordstrom’s 7-floor flagship store in New York City will be decked out with 253,000 feet of twinkling lights, starting the day after Thanksgiving [Nordstroms]

Santa Claus would have to travel at an average speed of 5.083 million miles per hour based on a 24-hour cycle to stop at each household on Christmas Eve [Popular Science]

Last year, Mariah Carey’s hit song “All I Want for Christmas is You” passed the 1 billion streams mark on Spotify [Billboard]

I know an executive at Nordstrom and they are particularly proud about not starting Christmas before Thanksgiving. Based on your post, Nordstrom must not either a) worry about same store sale discrepancies; or b) are hyper rational. I suppose a third option would be that the clientele at Nordstrom is high end enough not to care about holiday season sales. What do you think explains their approach to holiday time?

I believe there are also really high warehouse/storage costs this year compared to previously, making the alternative of storing the items before hand higher than normal. Not sure if this is part of the early push to get things out on the floor, too?