What Happened to All the Good Black Friday Deals?

Black Friday was once a single day of frenzied deals and early morning lines, but has morphed into a month-long shopping experience that seems to have lost some of its magic.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of over 2,900 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

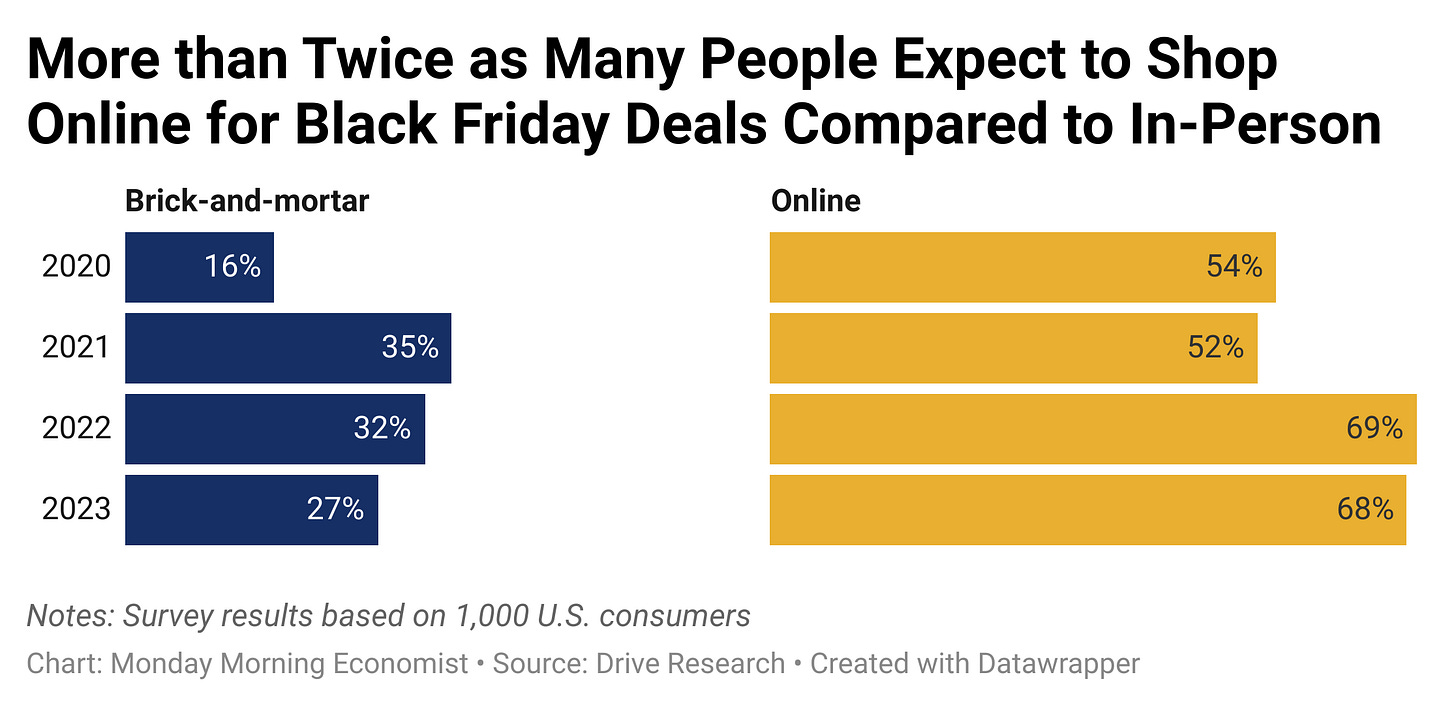

Last week, there was a social media uproar when Target was caught advertising Black Friday deals that appeared to be the same discount as the week before. People began wondering why Black Friday deals don’t seem as good as they used to. Not all that long ago, Black Friday was the ultimate shopping experience. People would camp out, fights might break out, but the allure of those exclusive deals made it all worthwhile. But times have changed. In the era of online shopping and digital empowerment, the traditional Black Friday story has taken a serious turn.

So, what happened? Well, it turns out, that not only are shoppers more sensitive to prices, but retailers are also playing a key role in reshaping the Black Friday narrative. Stores are extending the holiday discount season earlier and earlier to capture shoppers looking for great deals even before Thanksgiving. The result? Holiday deals start weeks before the actual Black Friday making the day itself seem, well, not nearly as exciting.

Black Friday is no longer confined to a single day; it’s a shopping season. Retailers have recognized the changing nature of consumer behavior and extended their holiday discount windows accordingly. Our previous anticipation of exclusive Black Friday deals has given way to a more prolonged shopping experience. This flexibility, however, means that the Black Friday sale that happens the day after Thanksgiving just isn’t what it used to be.

Explanation #1: Price Elasticity

When it comes to Black Friday shopping, our sensitivity to prices plays a big role. Consumers now have many more options when it comes to holiday shopping, thanks to online shopping and sophisticated price comparison tools. Imagine you're on the hunt for a new TV. Target isn't the only store selling them. In the past, they might have offered deep discounts on TVs to get you in the store, hoping you'd buy other items at regular prices.

But now, consumers can be pickier. They still want that steeply discounted TV, but they no longer need to purchase the not-so-marked-down items on the same trip. With the ability to compare prices across various retailers, consumer demand becomes more elastic. The result? Customers can make more informed decisions about when and where to purchase all their gifts. For companies looking to attract customers during the holiday shopping season, the next best alternative is to offer them deals earlier rather than steep discounts on one day.

Explanation #2: The First-Mover Advantage

Now, let's talk about the first-mover advantage. It's a big deal in business strategy. Being the first store to unveil holiday deals can produce a significant competitive edge. As consumers become more price-savvy, major retailers now initiate their holiday promotions weeks before the traditional Black Friday date.

The race to capture early shoppers has become crowded, with competitors launching promotions in rapid succession. The result? The uniqueness and impact of being the first to offer deals are diluted. Stores are offering discount prices for weeks, leaving little room for something special on the actual Black Friday.

The Shoppers’ Dilemma

In the age of information, consumers are no longer passive participants; they are empowered decision-makers armed with sophisticated tools. Price comparison websites and apps, such as camelcamelcamel, enable shoppers to review historical price data and discern authentic bargains from superficial discounts.

Armed with knowledge, shoppers are more discerning in their choices. The problem? These tools are available year-round. The once-legendary Black Friday deals no longer hold the same mystique. It's part of a broader evolution in the way consumers engage with holiday sales. Companies no longer have the ability to offer steep discounts one day out of the year because consumers are on the hunt for bargains all year long.

In a survey of 1,000 U.S. consumers, 26% have experienced being pushed or shoved by fellow Black Friday shoppers [Drive Research]

Black Friday shoppers spent a record $9.8 billion in U.S. online sales, up 7.5% from last year [CNBC]

The term “Black Friday” was coined around the 1960s by Philadelphia police officers [The New York Times]

Holiday sales were forecasted to increase by 3% to 4% from last year [National Retail Federation]

About one-third of U.S. adults had started their holiday shopping as of early October [Morning Consult]

Really interesting! The ideas around how market changes and consumer knowledge can change the shopping dynamic are very insightful.

From a different perspective - how about the idea that businesses moved things black Friday sales earlier as they assume this will increase sales (if they will buy tomorrow, why not have it today). This notion was referenced in the recent timing of pumpkin spice lattes being released earlier (or multiple amazon prime days). This would be then a short term profit increase at the expense of long term profits if people respond by assuming that they no longer need to purchase urgently, and thus reduce purchases during Black Friday season.

Of course, the above idea would imply that firms are either a. Irrational (don't maximize profits) or b. Have very high discount factors (profit this year trumps all future profits). The former is naturally an unsatisfying answers. The latter could be an issue with exec pay being tied to current success.