Is This World Cup a Waste of Money?

Qatar will spend more than $200 billion hosting the 2022 World Cup. What else could they have done instead?

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

The group stage of the 2022 World Cup wraps up this week in Qatar and millions of onlookers may be wondering if the host nation will see any meaningful benefits from the $200+ billion it has spent over the past 12 years. It’s hard to pin down how much of that is directly related to hosting the World Cup since Qatar also had to build a lot of the necessary infrastructure, which can be used after the tournament is over. The country spent around $36 billion on a new metro system for greater Doha, a new airport, extensive road construction, and over 100 hotels. These were built because of the World Cup, but they could be used for other purposes later.

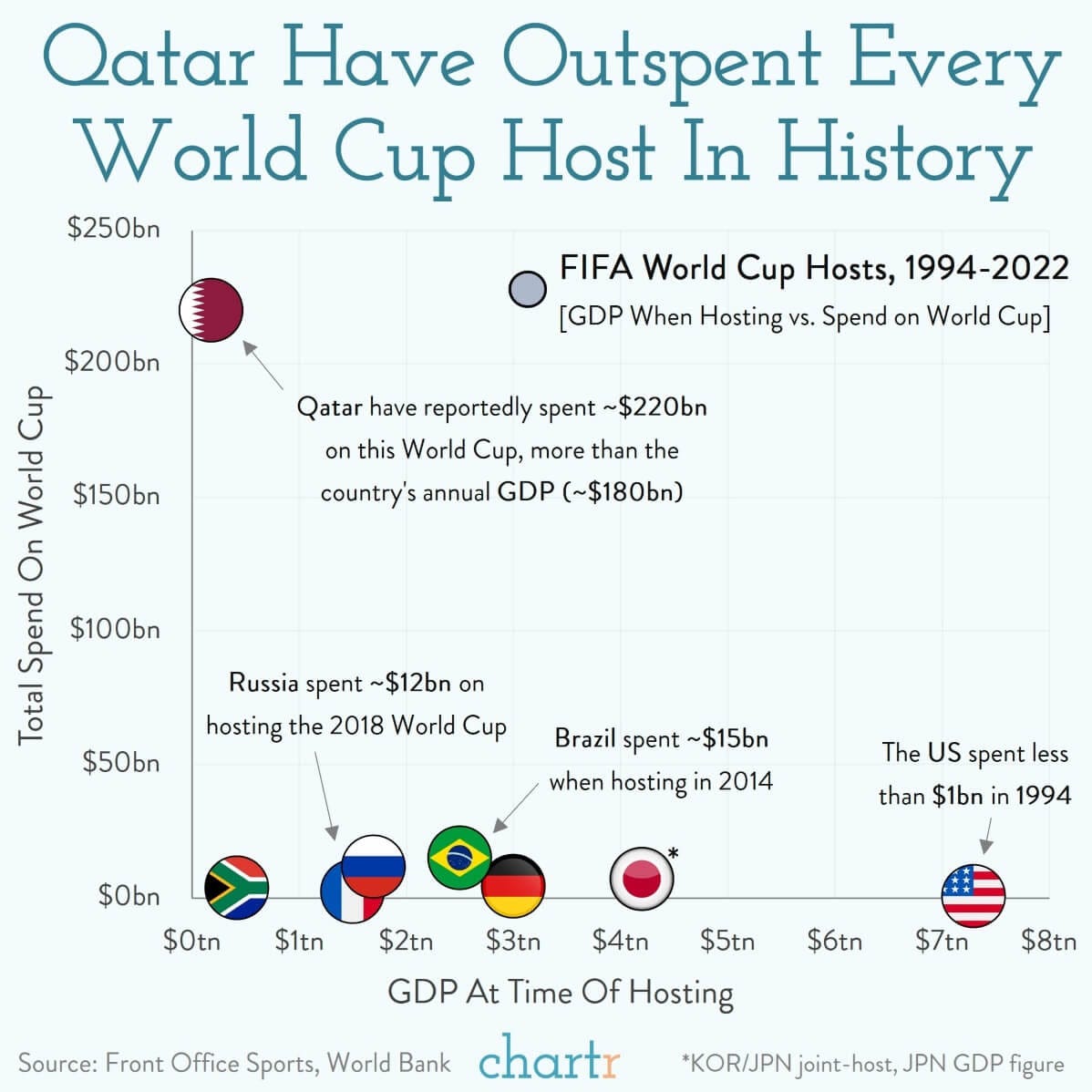

It’s hard to contextualize just how much Qatar spent to host the event, but some recent comparisons help. Here’s what other countries have spent to host the World Cup since the U.S. hosted it in 1994. I’ve adjusted the values for inflation and placed this year’s equivalence in parentheses:

United States 1994: $500 million ($1.01 billion)

France 1998: $2.3 billion ($4.21 billion)

Japan/Korea 2002: $7 billion ($11.60 billion)

Germany 2006: $4.3 billion ($6.11 billion)

South Africa 2010: $3.6 billion ($4.92 billion)

Brazil 2014: $15 billion ($18.88 billion)

Russia 2018: $11.6 billion ($13.77 billion)

Qatar 2022: $220 billion

Chartr also has a great graphic showing how this World Cup compares to others countries in terms of both spending and the host nation’s GDP when hosting. These values, however, haven’t been adjusted for inflation:

The costs of hosting the tournament will continue to grow after the World Cup ends on December 18. The hotels built for the surge in visitors will mostly sit unoccupied for the coming years. Some of the stadiums the nation has built will be dismantled and shipped elsewhere. The ones that remain will occupy valuable real estate, but will largely go unused. The maintenance costs will be directly seen, but the opportunity cost will be significant. Many host nations are famous for abandoning stadiums after mega-events are over.

Economists are often skeptical of the economic impact that mega-events like the World Cup or the Olympics has on a country’s economy. FIFA disagrees with those findings, but the projections of revenue and job gains are consistently overly optimistic. The decision to allow Qatar to host the games was rife with allegations of corruption from the beginning and has only been made worse by Qatar’s human rights record and the mistreatment of migrant workers. The typical narrative when the tournament is hosted outside of the most advanced economies is that event will showcase up-and-coming countries.

The main issue with presenting mega-events as a great investment is that host nations will never know how they would have fared had they not hosted the tournament and still spent the same amount of money on something else. In essence, we don’t have a great counterfactual. The parable of the broken window mirrors many of the same issues people when determining whether sporting events are worth the spending. The 19th-century French economist, Frederic Bastiat, asked readers to imagine that a vandal has destroyed the window of a shopkeeper’s store. The store’s owner must now pay a local glassmaker to repair the window. While it seems unfortunate, some people point out that the result seems to be positive since the glassmaker has more money that they can use to buy things from other people in town. As the glassmaker spends that income, they create more jobs and income for other people in town. Or does it?

When the proponents of sporting events (both big and large) argue that these events create these positive effects, they’re parroting the broken window fallacy. Supports often argue that the initial spending will create a multiplier effect and that the dollars spent on the games will have a broader impact beyond the initial amount. Their line of reasoning for the World is that visitors will come to Qatar and spend money at hotels and restaurants, and those owners will then have more money to spend elsewhere around the country.

Bastiat points out how this line of thinking is incorrect. While the glassmaker did earn more money due to the broken window, the original shopkeeper lost money. The shopkeeper may have been planning to spend that money on a new cart, but no longer can. Bastiat argues that we can’t judge a situation just by the impacts we can see, but that we should also consider the unseen costs as well. What spending might we not be seeing in Qatar?

What would Qatar be like if it had invested $200 billion dollars on airports, roads, healthcare, and education instead of connecting its current highway system to new stadiums? The “unseen” side of spending is often the hardest for people to consider in their calculations. It’s the opportunity cost that a nation faces when deciding what to spend money on. It’s easy to count the two million visitors who work their way through customs, but it’s harder to see the number of Qataris who leave while the tournament is hosted or the visitors who were planning to come for non-soccer activities but decided to skip visiting this year to avoid the crowds.

This isn’t to say that governments shouldn’t spend money on things that their citizens want just because it doesn’t create future revenue streams. I merely argue that it’s foolish for governments to advocate for these sorts of events on the grounds that they will pay for themselves when most evidence says otherwise.

There is a very powerful (and important) non-monetary benefit associated with hosting sporting events: civic pride. The people living in Qatar can brag for the rest of their lives that their country hosted one of the preeminent sporting events. Some families may cherish the memories of attending the event together, which will hopefully last for many years. That value, unfortunately, is really hard to quantify.

P.S. If you’re looking for a great read on the intersection of economics and soccer, I highly recommend Soccernomics by Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski.

The population in Qatar at end of October was 3,020,080 people, of which only 834,451 are female [Planning and Statistics Authority of Qatar]

One of the stadiums Qatar has built for the 2022 World Cup is made out of 974 shipping containers [Wilson Center]

Qatar has the most expensive beer in the world, with an average price of $11.26 per 33cl (330ml) bottle [Expensivity]

This year’s World Cup is expected to be viewed by 5 billion people [Morning Brew]

One of the first-ever officiated soccer matches in Qatar took place in Dukhan in 1948 [Sports Illustrated]

Here’s a bonus chart that I couldn’t fit into the story:

It is amazing how the same line is fed to people over and over again when sports are involved. JC Bradbury of Kennesaw State University has made it his life's work to dispel the myth of new stadiums generating untold riches. He's seen it at least three times in Atlanta where they keep building new stadiums while trotting out the tried and true line: Build it and they will come... but who "they" are, and where they come from is never properly addressed.

Interestingly with Qatar, their quest for prominence on the world stage might be undercut by the light shining on a number of ethically questionable practices that persist there. Furthermore, I wonder if anyone will remember the capitulations of FIFA the next time that corrupt organization goes on a human rights campaign. That clown who runs FIFA comparing his plight as a bullied child because of his red hair and freckles to the deaths of hundreds if not thousands of migrants and the inhumane treatment of LGBT peoples was appalling.