You’ve likely seen the green, yellow, and gray results of the viral game all over social media from your friends and those you follow. The online word game has taken the world by storm and spawned a number of one-puzzle-per-day copycat games like nerdle and lewdle (NSFW). There are an estimated 3 million Wordle players, which was enough to convince the New York Times to buy the hit game for at least $1 million. The full terms of the deal weren’t disclosed, but The Times hopes to grow their subscription-based platform.

The Times controls an online game portfolio that includes their famous daily crossword puzzle and other brain-teasers like “Spelling Bee” and “Vertex.” The company said its games were played more than 500 million times last year alone. This purchase, although not currently generating revenue, is likely to increase subscriptions to justify the 7 figure price tag. While a traditional newspaper business model focuses on advertising, The New York Times went subscription-based in 2011 and has focused on having its customers buy subscriptions to various platforms: print and digital news, games, recipes, product recommendations. Last month The Times purchased the sports news subscription site The Athletic and their 1.2 million subscribers for $550 million.

The current game subscription costs about $5 per month and The Times currently has more than a million subscribers already. The main concern among Wordle players has been what the purchase means for the previously ad-free gaming experience. Something that was previously free and available for almost everyone is suddenly at risk of being placed behind a paywall, restricted only for those who pay the subscription fee. In economics terms, the game was previously a public good.

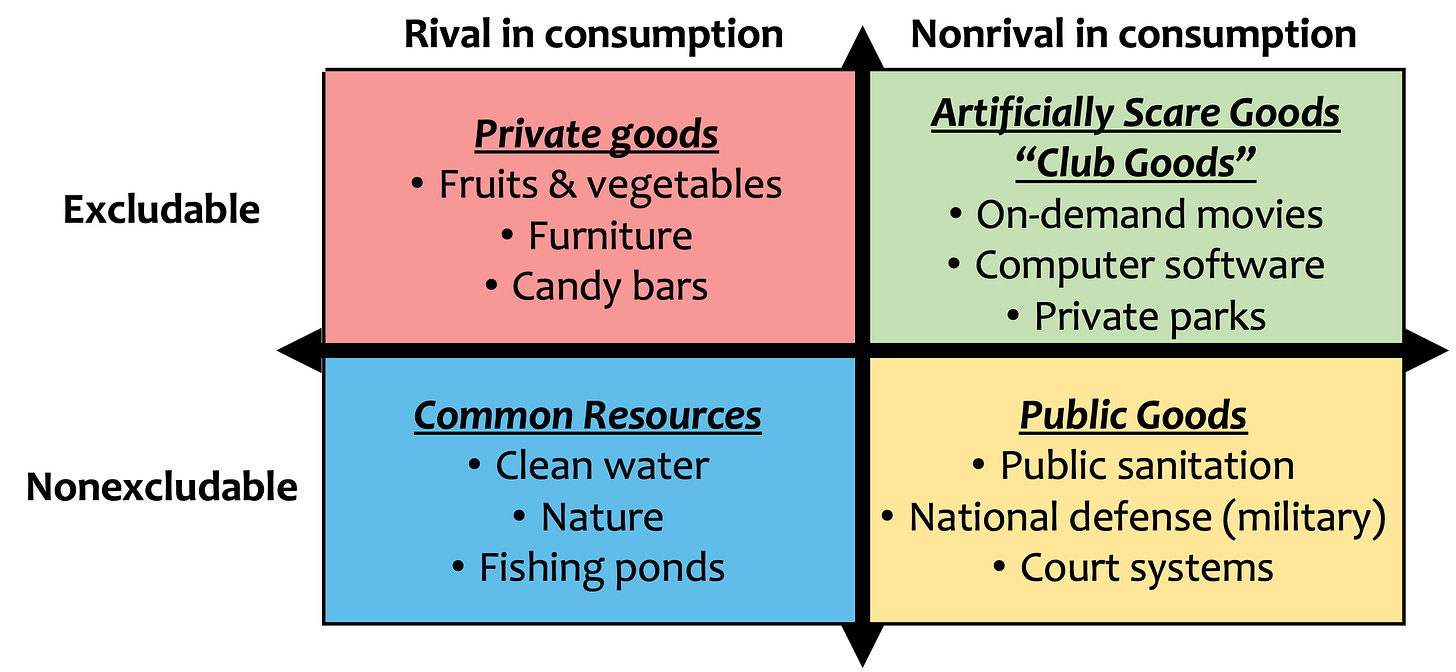

Goods and services can broadly be classified across two characteristics. The first looks at the rivalrous nature of the product. For a good to be rivalrous, it’s costly to allow another person to participate in the transaction. For the New York Times to sell another newspaper, it must incur printing costs associated with a physical paper, but not so with a digital article. The physical paper would be rivalrous, but the digital version is nonrivalrous.

The other broad characteristic looks at whether people can easily be charged for the item in question if they don’t pay for the product. For The Times, it’s fairly easy to require readers to have an account to access articles behind a paywall. As long as someone is paying the subscription fee, readers with login credentials can access the site. This makes many of their articles excludable. But Wordle’s creator (Josh Wardle) hasn’t made the product excludable, and it would take considerable time and effort to change that characteristic on the current website. And therein lies the concerns people have about the recent purchase.

Now that we know the characteristics of the original game, we can more carefully define the type of good Wordle represented. One more person playing the game didn’t change the cost structure by a noticeable amount, so the game would most likely qualify as non-rivalrous. Since the game’s original owner wasn’t charging anyone to use the game, he opted to create the game as being nonexcludable. These two characteristics define what economists call a public good. The economic version of public goods is often much broader than what goods and services people consider public goods.

While the rivalrous nature of the game will remain unchanged with the purchase, The New York Times would likely make the game excludable in the near future. Even though the cost of allowing one additional person to guess the five-letter word is essentially $0, the company may charge a non-zero price for access. This would take the previously designated public good and turn it into a club good (sometimes these are known as artificially scarce goods).

In competitive markets, the price of the product should be equal to the cost of the last product sold. In the case of Wordle, the cost of allowing one more person to play is essentially zero, so the price should be (and was) zero. This outcome would be considered efficient as it maximizes the number of people playing the game each day. If a non-zero price is imposed in order to play the game, then the number of people playing the game will decrease and The Times will have created some losses in society. The non-zero prices will generate profit for The Times, which could then be reinvested in new games for people to play.

The keyword there is that the company could create new games with the new profit, but this recent transaction is evidence of a more concerning outcome. There’s no requirement for the company to reinvest that money into new products. They could just as easily use the money to purchase other games that were available as a public good and turn them into a club good.

I can’t imagine a scenario where there would be any government intervention in the market for these types of online games, but there has at least been more recognition of market power and non-competitive behavior by firms in recent times. If Wordle does go under the subscription-based plan, and you don’t have a subscription to the platform, there are a number of other alternatives you can consider as well. Consider it the digital version of taking your (non-paying) business elsewhere.

The initial word list for Wordle included 12,000 words, but the final list contained only 2,500 words [New York Times]

There were 359,679 game results found on Twitter for Saturday, February 5th [@wordlestats]

Word-Cross (the original crossword) made its debut in December 21, 1913 in an edition of the New York World [It’s All a Game]

Crossword constructors can be paid as much as $2,250 if their puzzle appears in the Sunday edition of the New York Times [New York Times]

As of November 2021, 7.6 million of The Times’s nearly 8.4 million subscriptions are digital readers [The New York Times]

Oh, and I think an apt illustration of public and club goods is the MME! Right now it is a public good. The pay version you have proposed would make the additional content a club good. Correct?

Good analysis Jadrian. While Wordle is fun, if the format of the game remains "one word a day" it seems this would greatly limit the ability of the Times to monetize it. Who would pay for a game you can only play once a day? If a Wordle player isn't already a Times subscriber I can't imagine this would make them one.