Why the Paul Skenes Baseball Card Is Worth A Million Dollars

What makes this piece of cardboard—just ink, paper, and a small patch of fabric—worth more than an average house in Pittsburgh?

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

As a kid, I collected baseball cards. Not seriously—just the way most kids did. Buy a pack, swap a few cards with friends, and occasionally check a magazine to see if any of them were worth more than a dollar. We never really thought about them as investments, rather they were just something fun to do during recess.

But what if we had thought of it that way? What if, buried in one of those foil packs, there was a card that would one day sell for a million dollars?

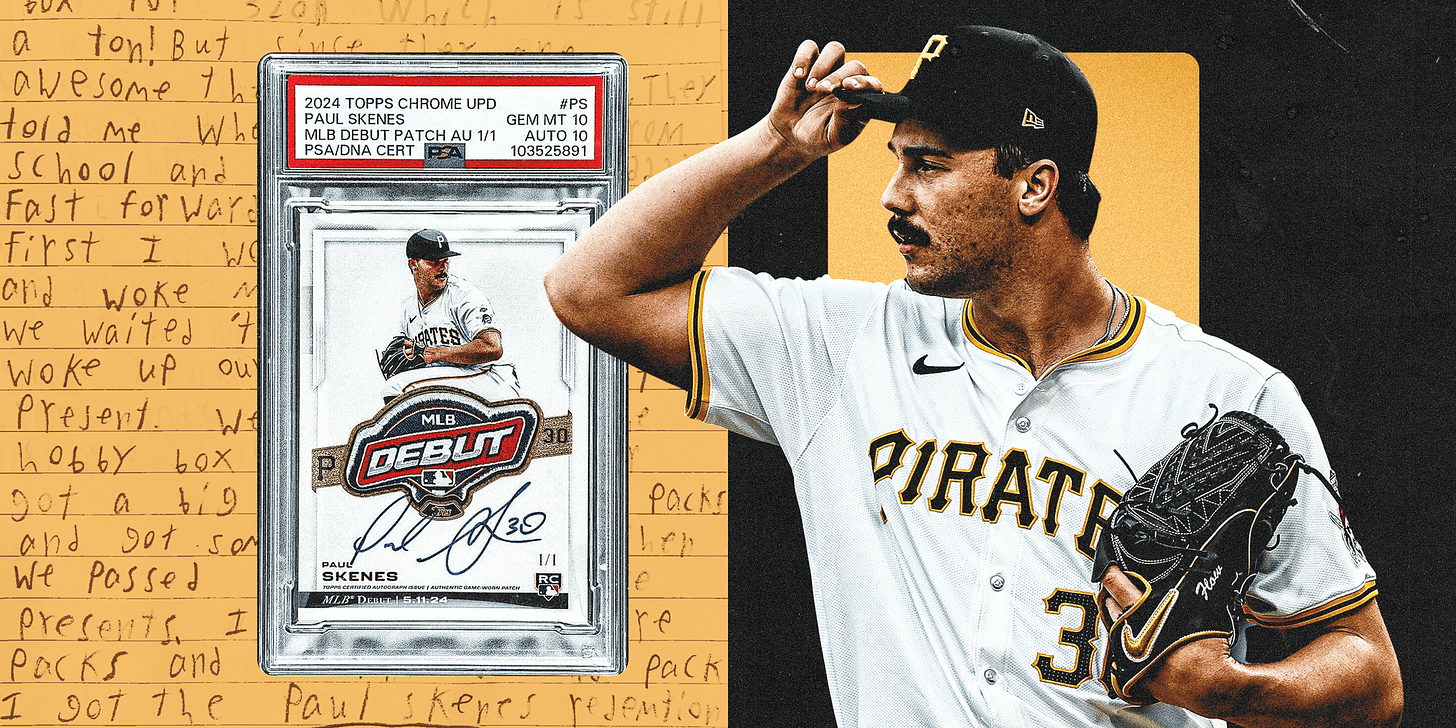

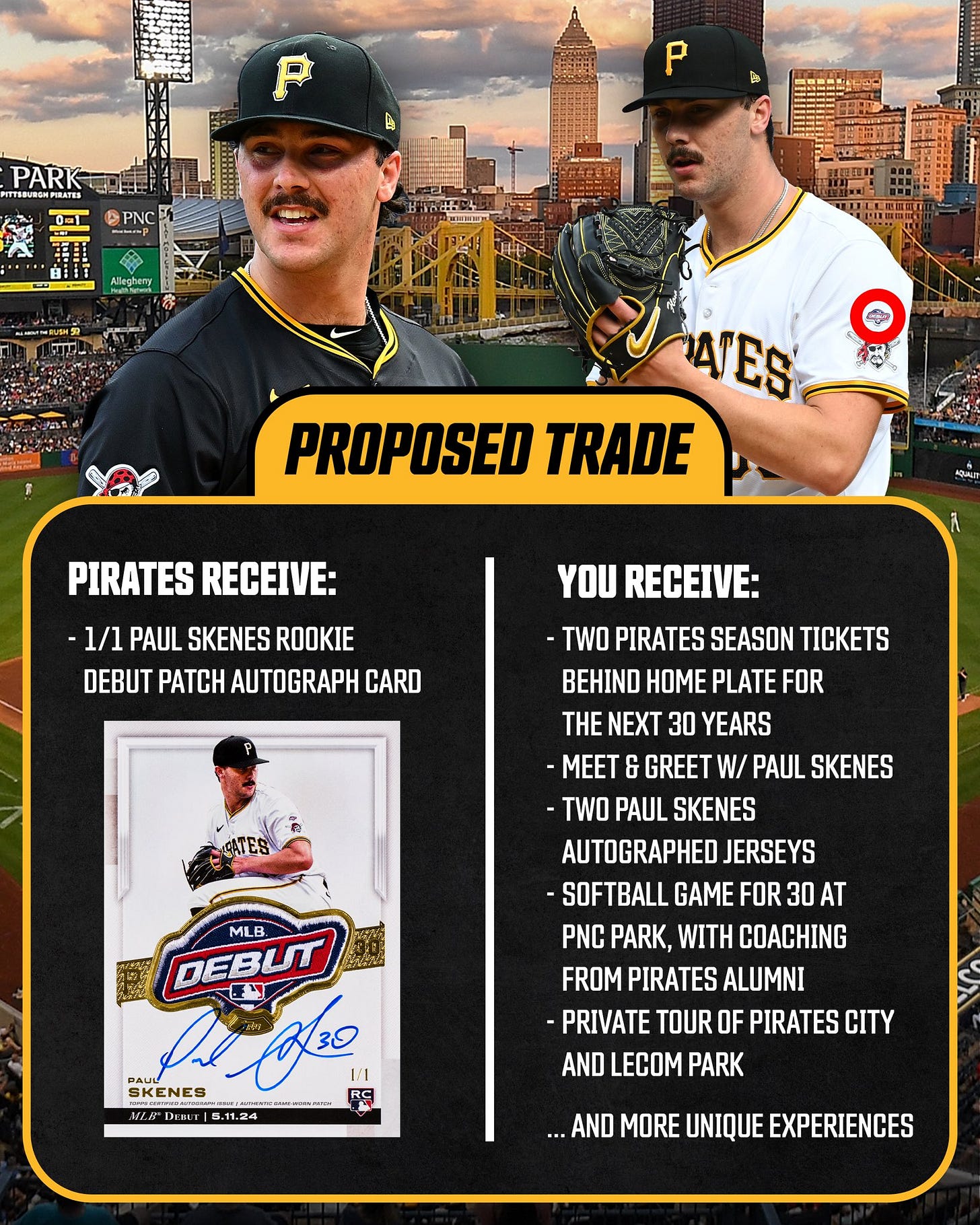

That’s exactly what happened with the Paul Skenes MLB Debut Patch card, a one-of-a-kind collectible that sent the sports memorabilia world into a frenzy. The card was so valuable that the Pittsburgh Pirates dangled 30 years of season tickets behind home plate along with a score of other amenities. Skene’s girlfriend, Olympian gymnast Livvy Dunne, offered a seat in her suite for the fan who found the card.

High-end collectors have speculated that the card could fetch $1 million at auction. But why? What makes this piece of cardboard—just ink, paper, and a small patch of fabric—worth more than an average house in Pittsburgh?

The answer, like so many things in economics, comes down to supply and demand. More precisely, this is what can happen when supply is fixed and demand keeps climbing.

Why Some Things Can Be Produced, and Some Can't

In most markets, when demand increases, so does the quantity supplied. If people suddenly crave more coffee, coffee shops will start grinding more beans. If a movie is an unexpected hit, theatres will offer more showtimes. Even collectibles like baseball cards and sneakers usually follow this rule. A player gets popular, and Topps prints another set. A shoe sells out, and Nike releases a restock. This elastic supply keeps prices from climbing too high.

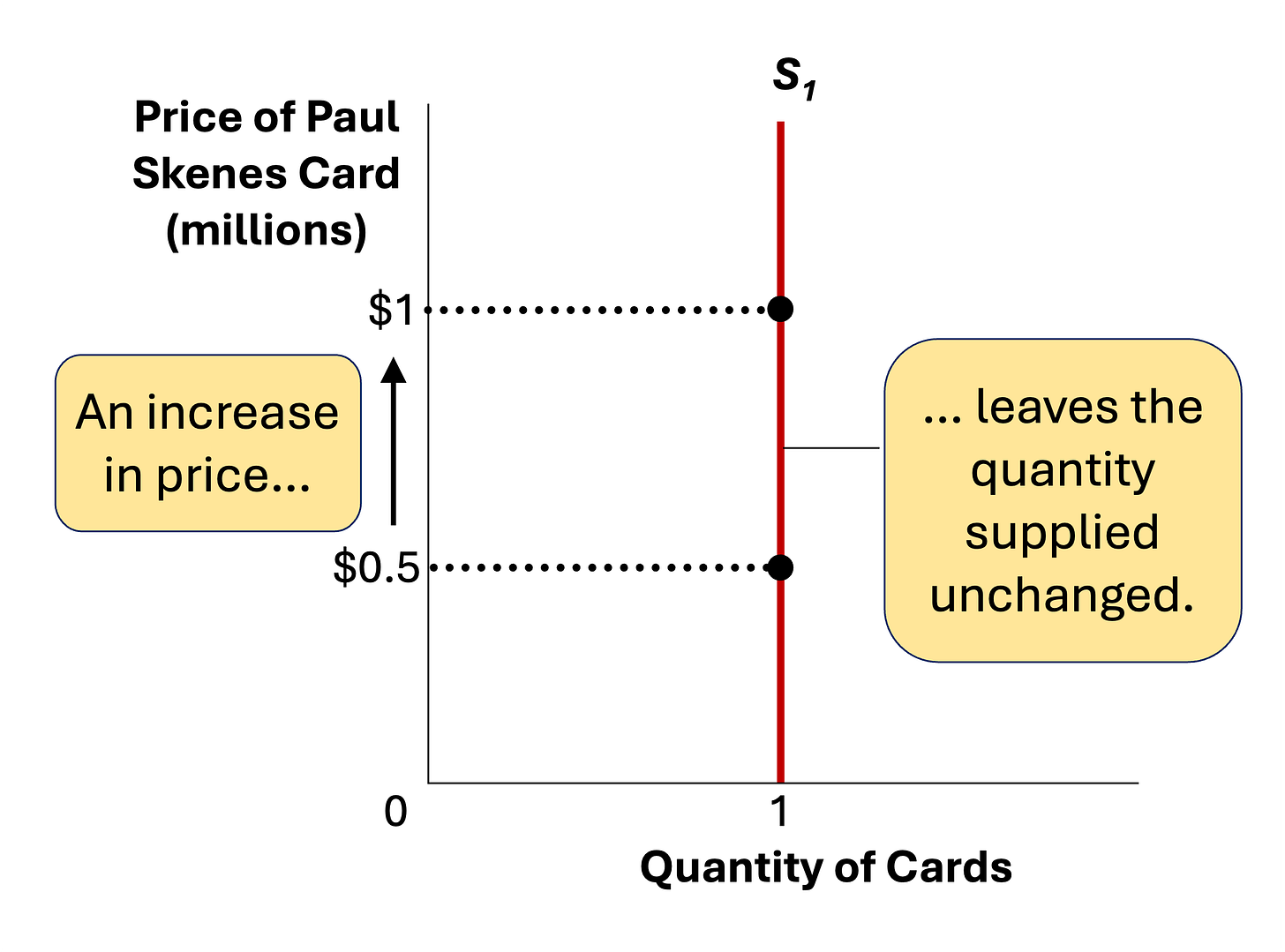

But this particular Paul Skenes MLB baseball card doesn’t work that way. There’s only one. Not one per store. Not one per print run. One, total. No matter how many collectors want this card, no matter how high the offers go, the current supply stays exactly the same.

This is what economists refer to as perfectly inelastic supply—a supply curve that is a straight vertical line. When supply is perfectly inelastic, price becomes the only thing that can change. Millions more may want this card right now, but since there’s no way to produce another card like this one, the price must increase to ration that single available card.

How Do You Ration Something That Can’t Be Reproduced?

In most markets, when demand increases, the price increases. This price increase serves as an incentive for firms to ramp up production but also as a way to slow down the demand for the product. But what happens when the price increases and firms can’t ramp up production? Often, the most popular way of rationing something so special is through an auction—whether formal or informal—where bidders fight over the right to own the one-of-a-kind item.

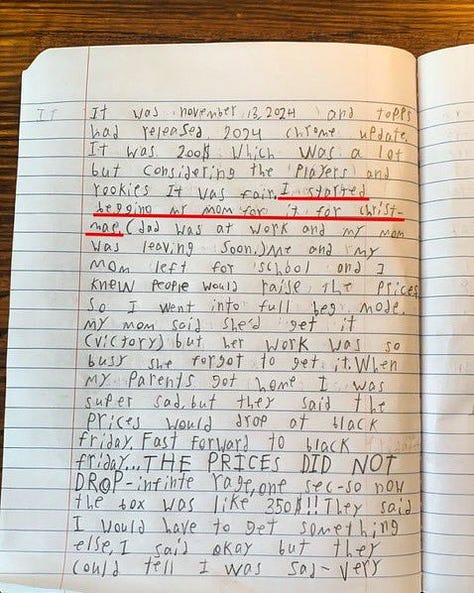

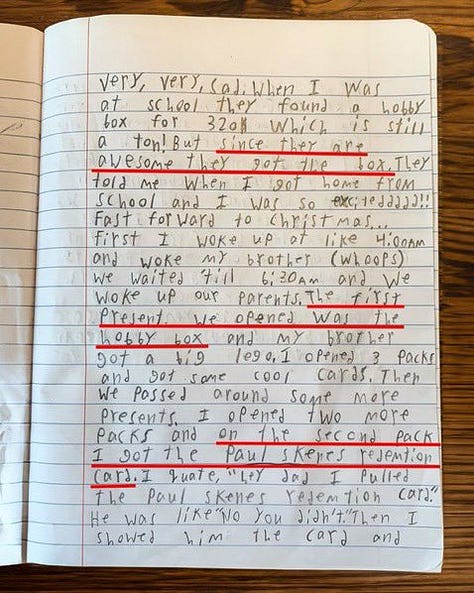

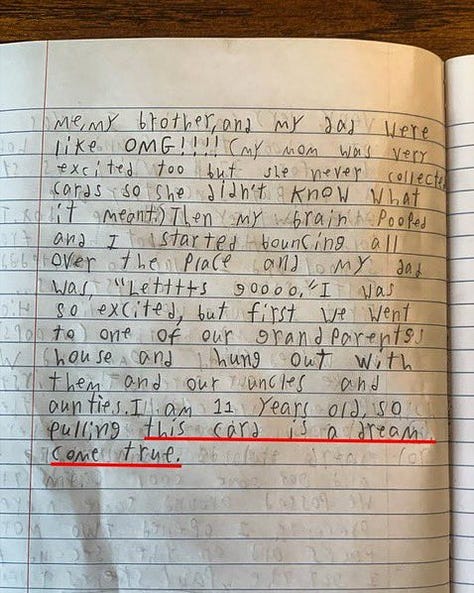

And that’s exactly what will happen with the Paul Skenes MLB Debut Patch card. The 11-year-old collector who pulled it from a pack could have taken the Pirates’ offer, but let’s be real—how much does a kid in Los Angeles care about 30 years of Pirates games? Instead, the card is expected to hit the auction block, where its final price will be determined the old-fashioned way: whoever is willing to pay the most, wins the card.

Compare that with baseball cards in general. Most players have multiple cards, and even rare ones are judged on condition, edition, and scarcity—not sheer existence. A scratched-up 1952 Mickey Mantle card is worth far less than one in mint condition. Even in the world of collectibles, supply isn’t usually fixed. Manufacturers can print more. Investors can release cards from storage. The market has ways to adjust.

Even commodities like gold and diamonds, while physically limited, aren’t perfectly inelastic. Miners can extract more ore if prices rise high enough. The supply curve isn’t a straight vertical line—it’s just really steep to reflect the increased cost of digging deeper into the earth.

But the Skenes card? There’s no warehouse full of extras. No second printing. No backup supply. That’s why a single pull from a pack—a piece of paper and fabric that cost the company a pennies to produce—is now being talked about in seven-figure terms. What will an 11-year-old do with that much money? They’ve indicated they will donate some of the proceeds to wildfire relief in Los Angeles.

Final Thoughts

The card’s final price isn’t about the ink, paper, or even the player—it’s about scarcity. It’s fascinating to watch these principles unfold in real time. As a former casual collector, I can’t help but wonder how many of my childhood cards ended up in the trash when they might have been worth something.

Some of you may be wondering: why would anyone spend $1 million on a small piece of cardboard?

Economists have a saying for this—“de gustibus non est disputandum.” Roughly translated: “There’s no accounting for taste.” We don’t judge what people value; we just observe what they’re willing to pay.

Most of us wouldn’t even consider dropping a million dollars on a baseball card. But someone will. And in a market where supply is perfectly inelastic, the price will be determined by just one thing—how much the highest bidder is willing to offer.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 6,300 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

Paul Skenes had a base salary of $740,000 in 2024 and is expected to earn $800,000 in 2025 [sportac]

Skenes and the Pirates reportedly agreed to a deal with a signing bonus worth $9.2 million, the largest MLB draft bonus ever doled out to a player [Sports Illustrated]

The current record price for an individual sports card is the $12.6 million paid for a 1952 Mickey Mantle baseball card on August 28, 2022 [Sotheby’s]

The Library of Congress has a collection of 2,100 baseball cards from 1887 to 1914 [The Library of Congress]

Arizona Diamondbacks owner Ken Kendrick is said to own the world’s best baseball card collection, worth over $100 million [Sports Collectors Digest]

Let me tell you about a little-known trading card game called Magic: the Gathering...

https://www.ign.com/articles/magic-the-gathering-the-one-ring-lord-of-the-rings-card-2-million-post-malone

But my question is why a Paul Skenes card, and not another player?