Why Pilots Are Turning Down Top Jobs

Pilots are choosing first officer roles for better work-life balance, despite higher pay for captains. This trend is challenging airlines to address job stress and quality of life issues.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 4,700 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

As the airline industry recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s facing a new kind of turbulence: a shortage of airline captains. The industry regularly cites a pilot shortage, but the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA), one of the largest global pilot unions, argues that there are enough pilots in the U.S.; airlines just aren’t offering competitive pay. To address current concerns, Congress will allocate $80 million over the next four years for pilot workforce development as part of FAA Reauthorization.

Pilot pay and benefits have increased significantly over the past few years, but a new issue has surfaced concerning pilot promotions. Despite the lucrative salaries associated with being a captain, many pilots choose to remain as first officers, favoring work-life balance over additional income. JetBlue founder David Neeleman highlighted this trend during Fortune’s Brainstorm Tech conference, highlighting two key economic concepts: compensating differentials and marginal utility. Understanding these two economic concepts can help us better understand why this shortage is occurring and what it means for the airline industry.

The Price of Working an Unpleasant Job

To understand why airline captains are paid significantly more than first officers, we need to start by looking at the concept of compensating differentials in labor economics. While it’s true that captains require more training and flight time—an investment in human capital that justifies higher pay—another key reason for the pay difference is compensating differentials. This theory argues that firms must pay higher wages to compensate employees for the less desirable aspects of a job relative to similar positions that aren’t as unpleasant.

These less desirable aspects of becoming a captain include substantial responsibilities and pressures. Beyond technical qualifications, the role demands long hours, unpredictable schedules, and extended periods away from home. Captains also bear the ultimate responsibility for the safety of the aircraft and its passengers.

Phil Anderson, a first officer with United Airlines, summed up the dilemma many pilots face in an interview with Reuters last summer: “If I took up the promotion, I would’ve ended up divorced and seeing my kids every other weekend.” This stark choice highlights the compensating differentials at play. Despite the financial perks, many pilots are deterred by the demanding schedules and immense stress associated with being a captain. For some perspective, United Airlines struggled to fill 978 captain vacancies last year—around 50% of all posted openings.

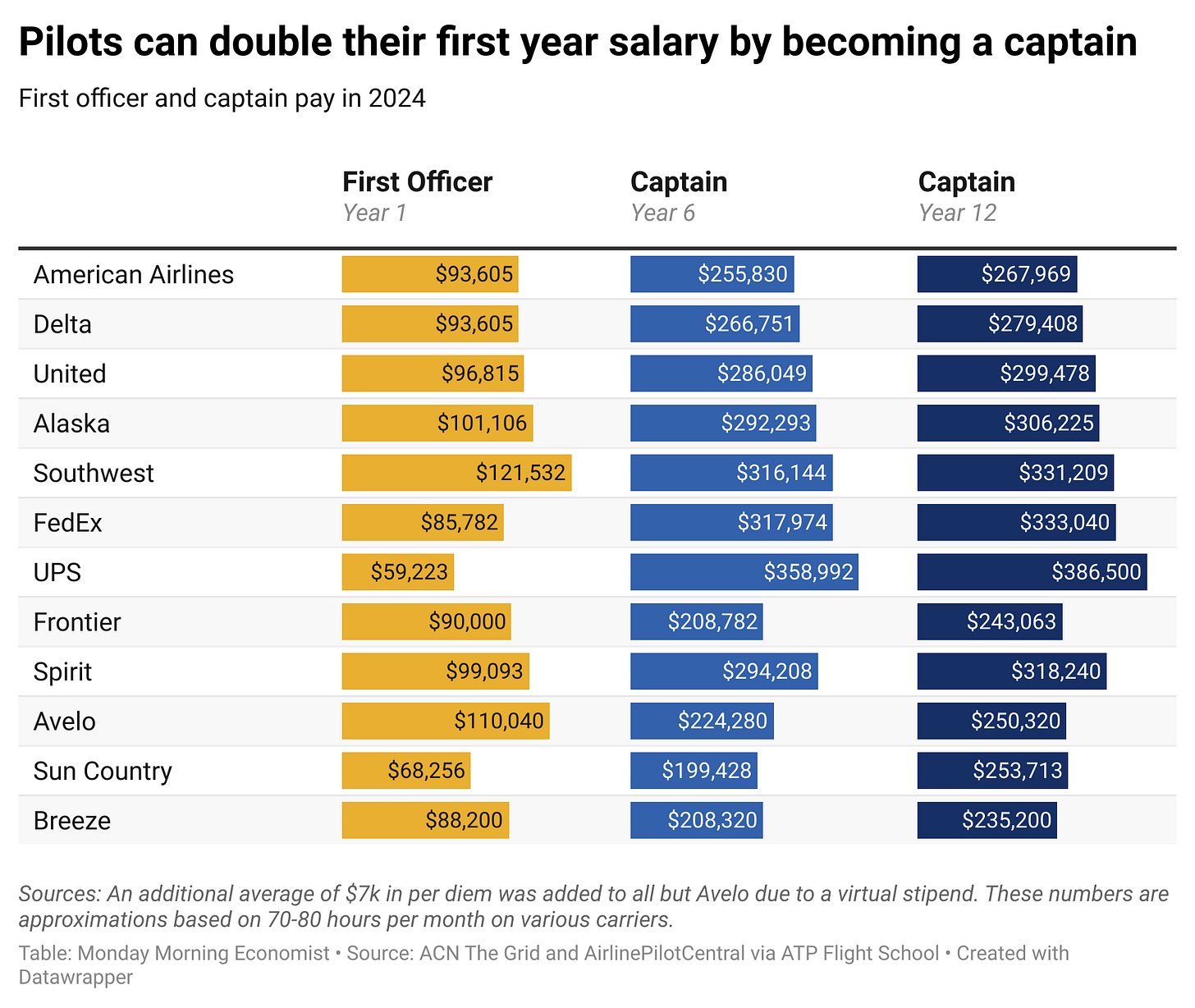

Experienced captains can earn up to $500,000 per year, while experienced first officers earn nearly $300,000. The sizeable pay gap is designed to attract pilots to the more demanding captain role. However, as JetBlue founder David Neeleman noted, the better quality of life as a first officer is causing many pilots to question whether the additional pay is worth the increased stress and responsibility. Moreover, the high salaries of first officers mean that the extra income from a promotion has diminishing returns on their happiness. This brings us to the concept of marginal utility of income, which helps explain why the allure of higher pay isn’t as strong as companies might expect.

The Diminishing Returns of Higher Income

To understand why many pilots are not enticed by the significantly higher pay associated with being a captain, we need to consider the concept of marginal utility—the additional satisfaction or benefit gained from consuming one more unit of a good or service. In this case, the good is income. As pilots earn more, the additional satisfaction they receive from each extra dollar diminishes.

For many first officers earning $200,000 annually, the jump to a $350,000 captain’s salary does not offer a proportional increase in satisfaction. The first $150,000 they earn has a meaningful impact on their life satisfaction, but the next $150,000 doesn’t pack the same punch. Of course, they’d be happier with more money, but the key thing to understand is that the additional income doesn’t generate as much happiness as the first amount they earn. And since their satisfaction isn’t increasing as much, it helps explain why the negative aspects of the job, such as increased stress, longer hours, and more time away from family, have a stronger impact on many people.

Scott Kirby, CEO of United Airlines, has also acknowledged this trend and noted its impact on the airline’s capacity in the fourth quarter of last year. When pilots prioritize quality of life over higher income, it reflects a broader shift in values, recognizing that beyond a certain point, additional income does not equate to increased happiness or well-being.

Final Thoughts

The shortage of captains poses significant challenges for airlines. Captains are essential for operating flights, and shortages could lead to reduced flight capacity and potential service disruptions. This shortage compounds the existing issues of pilot shortages, exacerbated by the pandemic. United Airlines and American Airlines have already admitted to feeling the strain, but more airlines could be next.

The International Air Transport Association reports that global plane passenger loads are returning to pre-pandemic levels, with domestic air traffic up almost 5% in May compared to last year. Despite this recovery in demand, the supply of pilots, particularly captains, remains insufficient. The industry faces an estimated shortage of 18,000 commercial pilots in 2023, further compounded by the reluctance of pilots to step into captain roles.

Airlines have ramped up pay and are increasingly hiring internationally to address these challenges. However, these measures may not be enough to resolve the deeper issue of work-life balance that drives pilots away from captain positions. While the Federal Aviation Administration has implemented regulations to mitigate physical and mental burnout—such as increasing mental health resources and mandating rest periods—pilots often hesitate to report mental health issues, fearing they will lose their flying licenses.

Rather than solely focusing on pay, airlines might find a more cost-effective solution by addressing the unpleasant working conditions of being a captain. By making the promotion to captain more attractive, airlines could potentially reduce the need for higher pay while encouraging more first officers to take on the role. This approach acknowledges the impact of diminishing marginal utility while also improving job satisfaction and overall well-being for pilots.

In May 2023, the median annual wage for airline pilots, copilots, and flight engineers was $219,140 [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

At American Airlines, over 7,000 pilots have opted not to take the captain upgrade, and the number of pilots declining the upgrade has at least doubled in the past seven years [Reuters]

Airline pilots average 75 hours of flying per month, but they spend an additional 150 hours each month on flight planning, obtaining weather forecasts, and other pre- and post-flight activities [Flying Magazine]

Frederick W. Finn holds the world record for the most air miles flown by a passenger, with a total distance of 22,370,000 km (13,900,000 miles) as of the end of June 2003 [Guiness World Records]

The solutions to these problems are really quite obvious, which is why the people at corporate making the decisions will never see them.