Why Do the Rich Vote?

Despite higher opportunity costs, wealthier voters consistently show up at the polls at a higher rate—a paradox that reveals a deeper economic rationale behind voting.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 5,700 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

As Americans head to the polls, an age-old question often comes up around this time: why do people vote at all? The decision to vote can seem a puzzle—especially for wealthier individuals who pay a higher opportunity cost for taking time away from work, family, or leisure. Yet these high-cost voters are more likely to show up at the polls. This behavior looks irrational at first glance, challenging the standard economic assumption that the marginal cost of time spent voting outweighs the marginal benefit of casting a vote.

After all, the odds of a single vote deciding an election are really small. So, why do people—especially those who could be doing something “more valuable” with their time—make it a point to vote? This question forces us to reconsider what it means to make rational economic decisions. What if voting isn’t about influencing the outcome directly but rather about “buying” something larger—a chance to affect the entire country?

The Case Against Voting

The standard economic approach to decision-making focuses on weighing marginal costs against marginal benefits. At face value, voting presents an obvious set of costs: there’s the time spent registering, researching candidates, and heading to the polls. These activities require individuals to set aside time that could otherwise be used for other productive purposes. For wealthier, highly educated individuals, the cost of that time is even steeper. Some would argue that they may have “more valuable” ways to spend their time.

Then there’s the question of impact. In a major election, the probability that a single vote will decide the outcome is, statistically speaking, next to zero. Millions of votes are cast in federal elections, and one vote is unlikely to be the tipping point. Economists call this the “paradox of voting”: the cost of voting tends to outweigh the benefit of influencing an election’s outcome, making it seem irrational to invest time in the process.

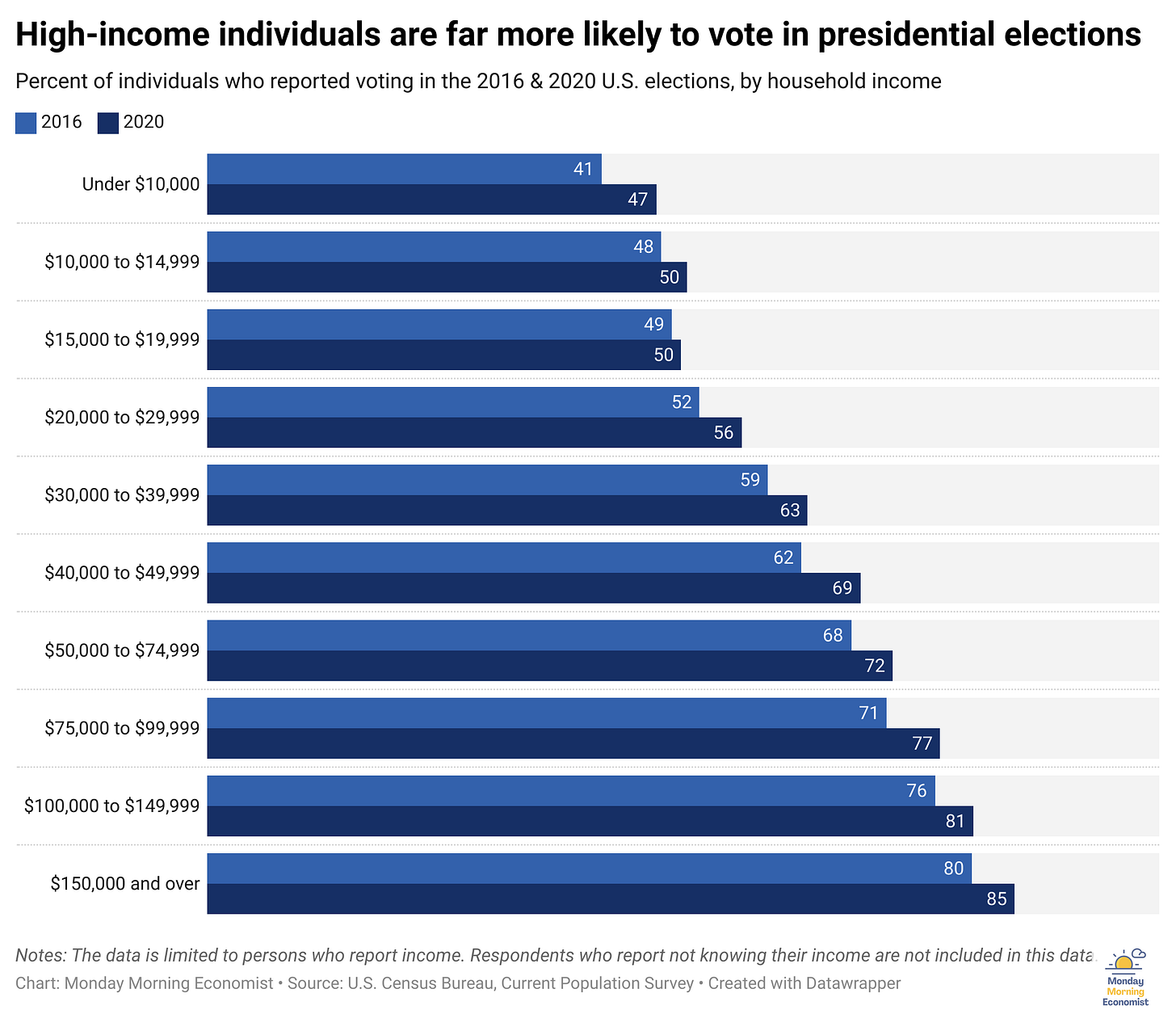

But here’s where it gets puzzling. Despite this logic, voter turnout consistently shows that richer and more educated individuals vote at higher rates than others. By classic economic logic, this shouldn’t be the case. Those with lower opportunity costs should be voting more often. So why doesn’t this theory match up with the actual data?

Reframing Opportunity Cost

We need to shift how we think about opportunity costs away from the immediate costs of voting to the longer-term risks that voters may be trying to avoid. The traditional view of opportunity cost—time lost to registering, researching, and casting a ballot—misses a larger point. The true opportunity cost isn’t just a few hours; it’s the potential consequence of electing the “wrong” candidate and the policies that might follow.

This reframing offers a broader view of opportunity cost—one that includes the potential future costs of unfavorable policy decisions. For example, policies around taxes and regulations often have a bigger impact on wealthier individuals’ investments and business interests. So, when these voters see a significant risk that their assets could be adversely affected, voting becomes a kind of “insurance” against the cost of unfavorable political outcomes.

When framed this way, voting becomes a rational choice for those with the most to lose. Even if a single vote is unlikely to determine the election, the collective voting patterns of similarly motivated individuals can help sway policy outcomes over time. We shouldn’t view casting a ballot as just about making a one-time decision; it’s more like a small investment in a long-term outcome.

Final Thoughts

The economic rationale for voting becomes clearer when viewed through this broader lens: while the costs of voting are real, they seem small relative to the perceived risk of policies that could undermine personal and financial security. For those with a lot at stake, voting isn’t irrational—it’s a carefully considered choice based on a broader view of opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of not voting could now be much larger.

Though a single vote is unlikely to decide an election, the collective impact of consistent participation within certain demographic groups can influence policy outcomes. So as you head to the polls—or decide not to—remember that analyzing simple decisions can be much more complex than at first glance. The decision to vote isn’t just about today; it’s a hedge against policies that could affect your future. Perhaps, then, the choice to vote is one of the most rational choices you can make after all!

From 1976 to 2021, more than 85 U.S. Senate elections were decided by less than 3 percent of all votes cast [The Center for American Progress]

A little more than one in three U.S. adult citizens — 37% — say they did not vote in the 2022 congressional elections [YouGov]

The most common reason for not voting in the 2020 presidential election among registered nonvoters was they were not interested in the election (17.6%) [U.S. Census Bureau]

Seventy-one percent of Americans say they have given “quite a lot” of thought to the upcoming presidential election, which is on par with election year readings at similar points in the 2008 and 2020 campaigns but higher than in 2000, 2004 and 2012 [Gallup]

I wonder if with the advent of new technologies, mainly smart phones, these costs are diminishing. You can do a significant amount while getting to a poll/waiting in line.

Would be interesting to see a historic rate of voting the rich.

Voting isn't a cost/benefit analysis on the actual power of my vote. It is an opportunity to be a. patriotic, b. part of a collective / tribe / team, c. tell politicians they are doing well or poorly based on the intensity of the vote for / against them, d. and finally, the contradiction to my point: real laws (ballot measures, state constitutional amendments). For people who vote in states where the other party tends to win vs their own choice of party, we know we are going to lose most votes, but we still want to encourage our own party to keep going because there are people who believe in them.

And as always, Jadrian, very nice post.