What’s the most popular Christmas movie of all time?

Let's look at the box office–and inflation–for the answer!

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Every holiday season comes with the same age-old debate about which movie is the best Christmas movie. Is it the nostalgic warmth of It’s a Wonderful Life? A heartfelt comedy like Home Alone? Or maybe something more modern, like How the Grinch Stole Christmas? Inevitably, someone throws Die Hard into the mix, sparking yet another round of arguments over whether it even qualifies as a Christmas movie. Spoiler alert: the answer might depend on your age.

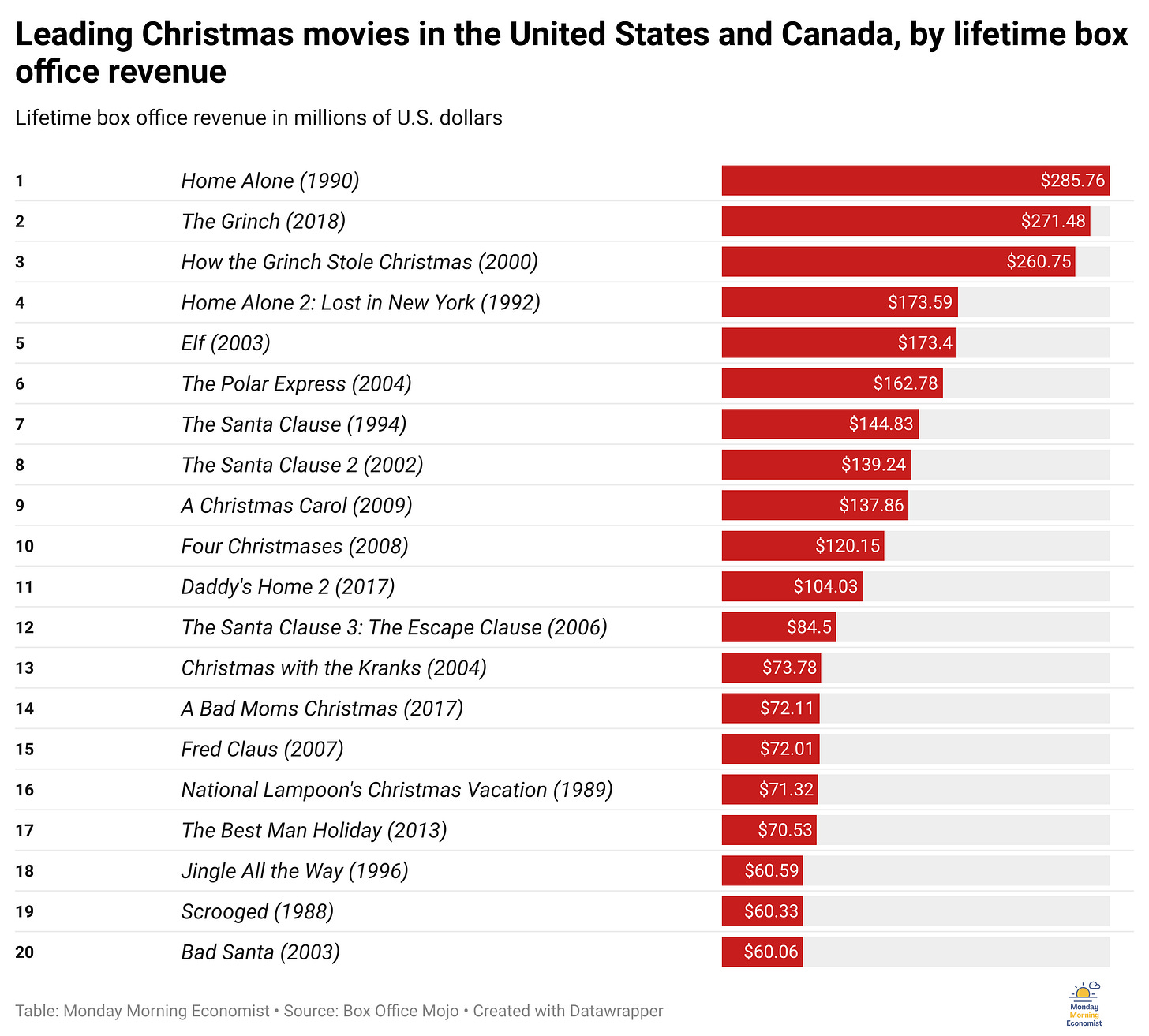

This year, let’s settle the debate with data. We’ll use box office numbers, specifically lifetime domestic earnings from the U.S. and Canada, to rank Christmas-themed movies. After all, dollars don’t lie, right? People voted with their wallets, and the highest-grossing films clearly stood out from the rest of the pack.

But as any good economist (or holiday movie enthusiast) knows, the story doesn’t end there. But box office revenue alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Inflation skews some of these numbers since ticket prices have increased over time. Just so we’re clear from the beginning, I’m relying on data from Box Office Mojo’s Christmas Theme Genre, which does not include Die Hard and only goes back to 1983 when A Christmas Story was released. Ready to settle the debate? Let’s crunch some numbers.

The Challenge of Comparing Movies Across Time

Let’s start with the raw numbers. If we ranked Christmas-themed movies by their lifetime domestic box office earnings—without adjusting for inflation—the top spots would go to Home Alone (1990) and The Grinch (2018). Home Alone generated over $285 million in U.S. and Canadian theaters since its release on November 16, 1990, while The Grinch pulled in more than $271 million nearly three decades later.

These are some impressive numbers, but they come with an important caveat: these figures are measured in nominal dollars. Nominal dollars represent the original price: no adjustments, no context. They tell us how much revenue a movie brought in at the time it was released, but they don’t tell us how much a dollar was worth back then versus today.

You can also think of inflation in the context of how much the price of a movie ticket has changed. The average movie ticket cost around $4.23 in 1990 but climbed to about $9.11 in 2018. That means a movie that sold the same number of tickets in 2018 as Home Alone did in 1990 would generate more than double the nominal revenue just from selling those tickets at higher prices. So, while The Grinch’s 2018 performance is impressive, part of its success is due to higher prices, not necessarily a larger audience.

This is the most obvious limitation of nominal values. They’re easy for us to understand, but they don’t tell the full story. To really compare movies that were released decades apart, we need that data to reflect what economists call real values. Real values would account for inflation to allow us to compare box office revenues as if all movies were released in the same year. And as you’ll soon see, some of those rankings begin to shuffle around.

Why Inflation Matters (and Why It’s Tricky)

To compare box office revenue across time, we need to account for inflation—that steady increase in prices that makes today’s dollar worth less than last year’s dollars. This is where the Consumer Price Index (CPI) comes in. The CPI is one of the most commonly used measures of inflation and tracks the changing cost of a basket of goods and services over time. We can convert nominal box office data into real dollars by adjusting the values with the CPI. The adjusted values will allow us to compare movies as if they were all released in the same year.

But while the CPI is an important tool for economic analysis, it’s not without its quirks. For one, the index measures average price changes across a broad range of goods and services, from housing and food to medical care. Movie tickets are just a tiny part of that calculation. The CPI gives us a reasonable estimate of inflation, but it might not perfectly capture changes in specific markets like entertainment, where factors like ticket pricing strategies, theater upgrades, and even cultural shifts play a big role.

Take the 1990s, for example. Back then, a trip to see Home Alone was a major event for families during the holidays. Today’s audiences, however, might just stream a new holiday release from the comfort of their couch. These shifts—the rise of streaming and the decline of physical moviegoing—aren’t easily captured by the CPI. But they highlight why comparing box office performance across decades is no simple task.

Even with these limitations, inflation adjustments still reveal a lot. Adjusting for inflation shows just how dominant Home Alone was at the box office compared to all the other Christmas movies. Just to be clear, Home Alone wasn’t just a holiday hit. It was the third highest-grossing film in 1990, despite being released in November. It was the #1 film at the box office several weeks after Christmas and would eventually be the highest-grossing among all 1990 releases.

For the rest of the rankings, the top 10 Christmas movies largely stay the same, but inflation adjustments shift the order by one or two spots. Older classics like National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989) and Scrooged (1988) climb several spots in the ranking, highlighting the importance of adjusting for inflation. While CPI adjustments may not be perfect, they’re an important step in answering our original question: which Christmas movie really stands the test of time?

Final Thoughts

Even after adjusting for inflation, box office numbers still only tell us so much. A movie’s financial success doesn’t always translate into cultural significance. For example, It’s a Wonderful Life flopped at the box office but went on to become one of the most beloved Christmas movies of all time. And in today’s streaming era, some Christmas movies—like The Christmas Chronicles or Happiest Season—aren’t even released at theatres. Streaming success there is measured in views and subscriptions rather than dollars. Comparing these movies to box office hits like Elf (2003) or The Polar Express (2004) requires an entirely different approach.

So, is Home Alone the greatest Christmas movie of all time? I guess that answer depends on what you’re measuring. And that’s the beauty of both economics and holiday traditions: they’re endlessly debatable, deeply personal, and always worth a second look.

In a survey of U.S. adult who say they’ve seen Die Hard, only 39% say that it should be considered a Christmas movie [YouGov]

Christmas in Wonderland was released in 2 theatres in 2008 and earned a total of $689 at the box office [Box Office Mojo]

Home Alone generated $11,510,542 in box office revenue in France when it was released [Box Office Mojo]

In its first week of release in 2018, more than 20 million Netflix subscriber households streamed The Christmas Chronicles [Deadline]

In 1974, It’s a Wonderful Life entered the public domain after the film’s copyright holder simply forgot to file for a renewal [Mental Floss]