What Would You Do Differently if You Didn’t Have a Commute?

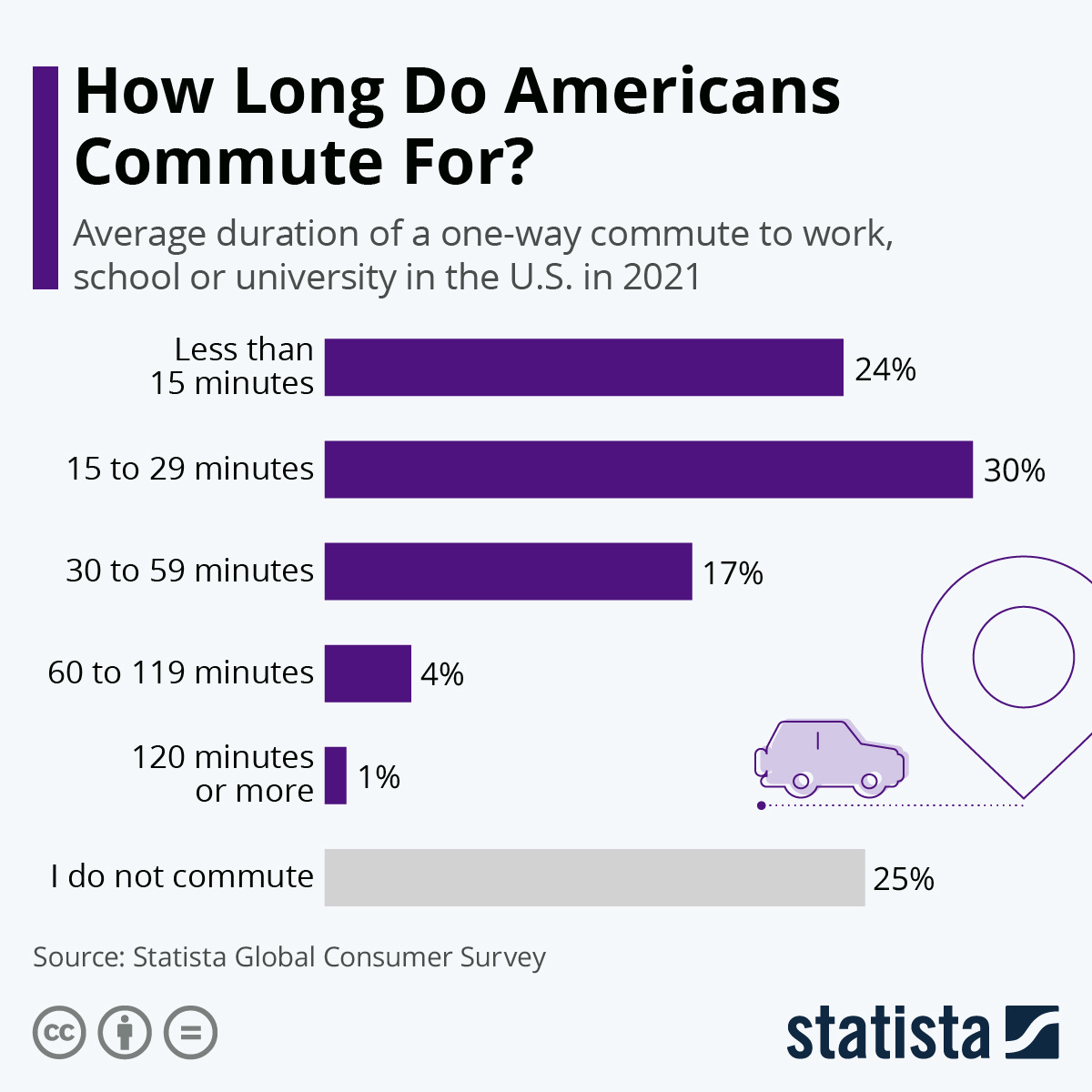

As workers switched to remote working arrangements, they suddenly had an extra hour available each day that wasn't being spent on commuting time. How would you spend an extra hour each day?

What would you do if you had an extra hour every day? Would you head to the gym for some extra cardio or would you find a comfy spot on the couch to watch your favorite new tv show? Maybe you’d start reading more often or pick up a new hobby? Many workers over the past two years have found an extra each hour as their commute time disappeared with the shift to remote working options. Using detailed data from the American Time Use Survey, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that employed individuals are allocating their saved commute time toward leisure activities and sleep, all while reducing overall work hours.

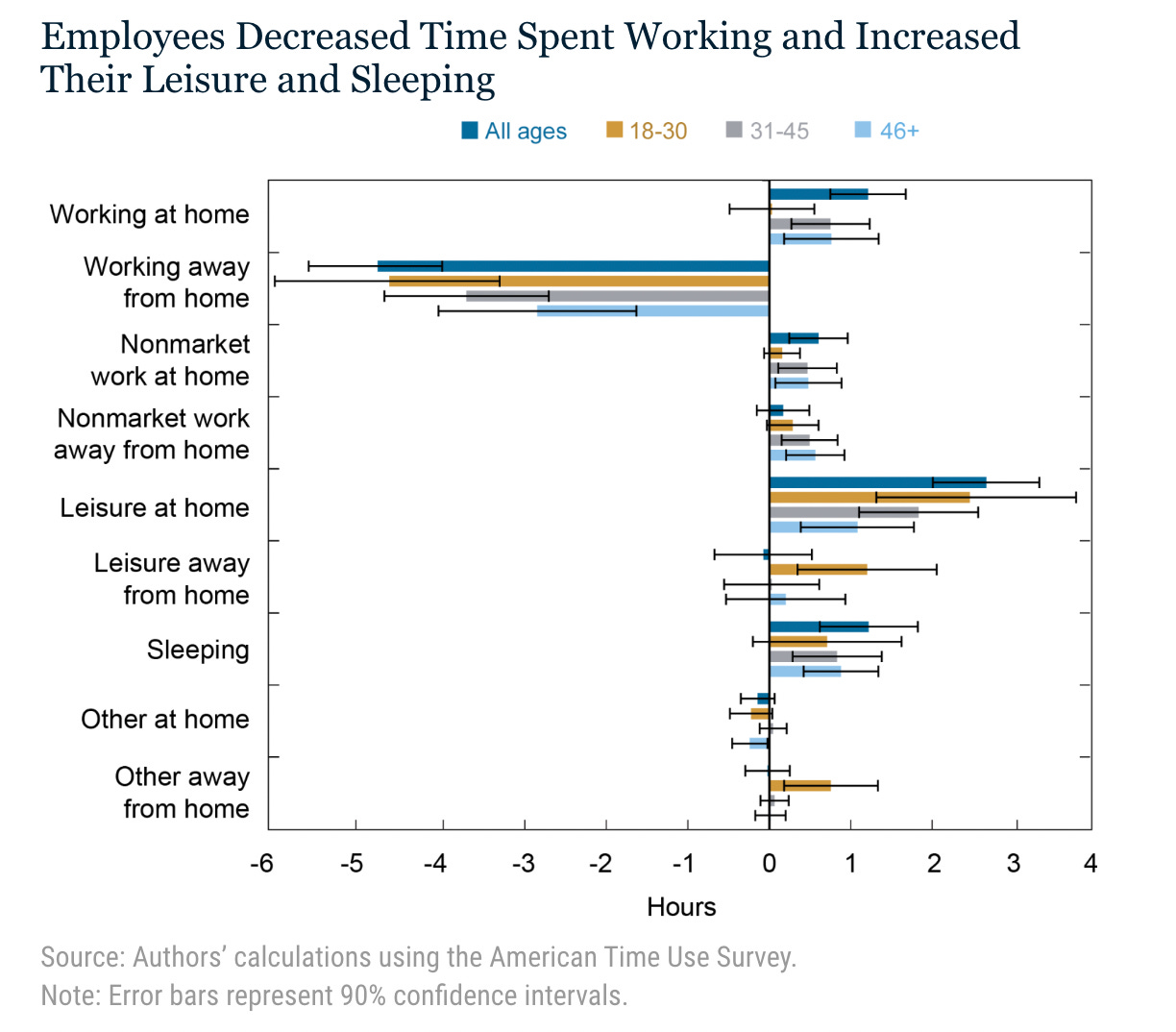

While an increase in sleep or leisure activities may not be that surprising, the reduction in hours worked may seem counterintuitive. Their result is consistent with earlier work that found remote options led to an overall decrease in the number of hours worked. The NY Fed’s analysis was restricted to employed individuals to exclude reductions in commute times that were actually due to job loss and a subset of their analysis looked only at full-time employees to account for the potential that the pandemic caused firms to cut hours for remote workers.

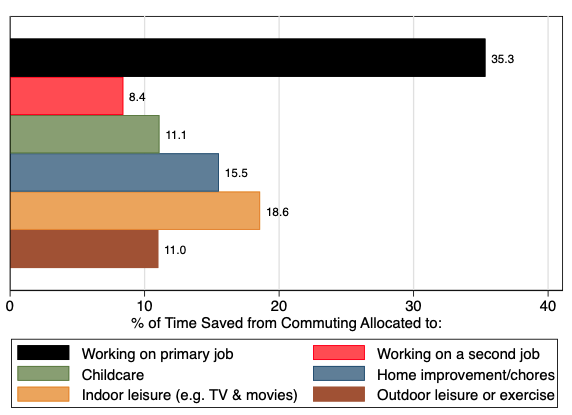

In the early stages of the pandemic, surveys found that remote workers reported allocating 35% of their new time savings directly toward their primary job. The next largest category (18%) was indoor leisure activities, which included reading and watching TV or movies. What people say they do, however, doesn’t always line up with what they actually do. In economic terms, people’s stated preferences differ from their revealed preferences. The new result suggests that although individuals may have increased their time working in the precise time slot they used to allocate toward their commute, overall time spent in paid work during the day decreased because workers substituted toward other activities throughout the day.

Here’s a summary of that earlier survey that asked 5,000 U.S. residents (aged 20-64, earning more than $20,000 per year in 2019) how they allocated their commute time to other activities. The survey asked people working from home the following question:

During the COVID-19 pandemic, while you have been working from home, how are you now spending the time you have saved by not commuting?

A reduction in commuting time represents a reduction in the cost of working. For some, that’s related to owning a car, but driving less and for others, it may be canceling their metro passes or paying fewer bus fares. Many of us often think of work as purely increasing income, but there are a variety of costs that workers incur before they ever earn their first paycheck. These costs include training costs or certifications that are required for the industry, work-specific clothing, and even daycare costs. These costs can be prohibitively large enough (especially daycare) that many people don’t have the means to even start a new job.

Before the pandemic, full-time workers averaged 8.5 hours per day working and 1 hour per day commuting, making their effective work day 9.5 hours long. That extra hour spent commuting was unpaid work for many workers. Getting that hour back doesn’t change the hourly pay associated with their job, which means that the new hour is similar to an increase in their income. You can think of it in the same way as receiving an end-of-year bonus or winning a smaller lottery. Instead of a $5,000 increase in income, remote workers received 250 more hours of their life back during the year.

Lottery winners, even the jackpot winners, aren’t likely to quit their jobs over the increased income, but they will probably work less. We wouldn’t expect them to suddenly start working more hours per week. The income effect is a measure of how workers change the allocation of their time based on changes in income while their hourly pay remains unchanged. For increases in income, like a bonus check or commute time reductions, workers should decrease the hours they spend in paid labor and allocate some of that time toward leisure activities or household maintenance.

Thankfully, that prediction is consistent with the results of the new research. Overall time spent in paid work decreased while there was a notable increase in leisure time and sleeping. Increased leisure was most pronounced among younger Americans while older age groups were more likely to allocate time to childcare or household maintenance.

Here are the official results, broken down by time category and age range. The black lines on each bar are known as “error bars” and represent the range of values that someone could expect if there was a mistake in reporting the data. If that error bar crosses over the middle line, you can interpret the result as being statistically insignificant, which means the researchers believe the change isn’t likely to be different than zero:

The work is an interesting real-world exploration of a common problem facing many Americans and may explain a portion of various reports on employees’ preferences for flexible working arrangements since cutting commute times allows workers to allocate their time to be more aligned with their preferences. It may also explain why remote workers generally report being happier if more time is being allocated toward fun activities and less time is spent on work-related activities. It’s similar to the findings and arguments in favor of a 4-day workweek, but will inevitably be an important consideration for the future of flexible work arrangements.

Americans now spend 60 million fewer hours traveling to work each day [Federal Reserve Bank of New York]

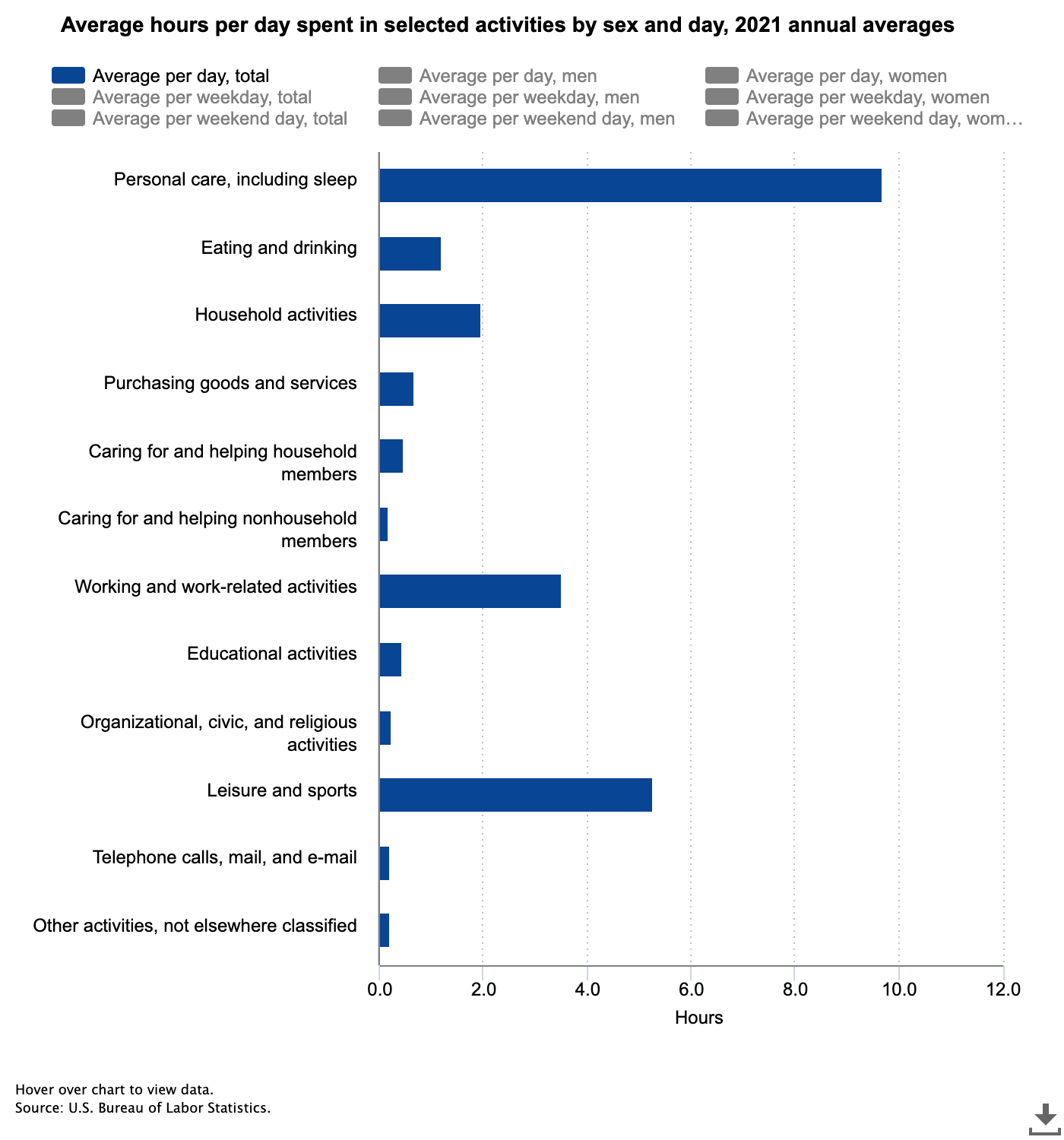

The average American spent 8.28 hours per workday in 2021 on “work and work-related Activities” [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

In 2019, the average one-way commute in the U.S. increased to a new high of 27.6 minutes [Census Bureau]

Before the pandemic, remote workers earned 5% more than traditional officer workers [Labour]