We Can’t Build Bananas in America

Comparative advantage still matters in trade debates

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

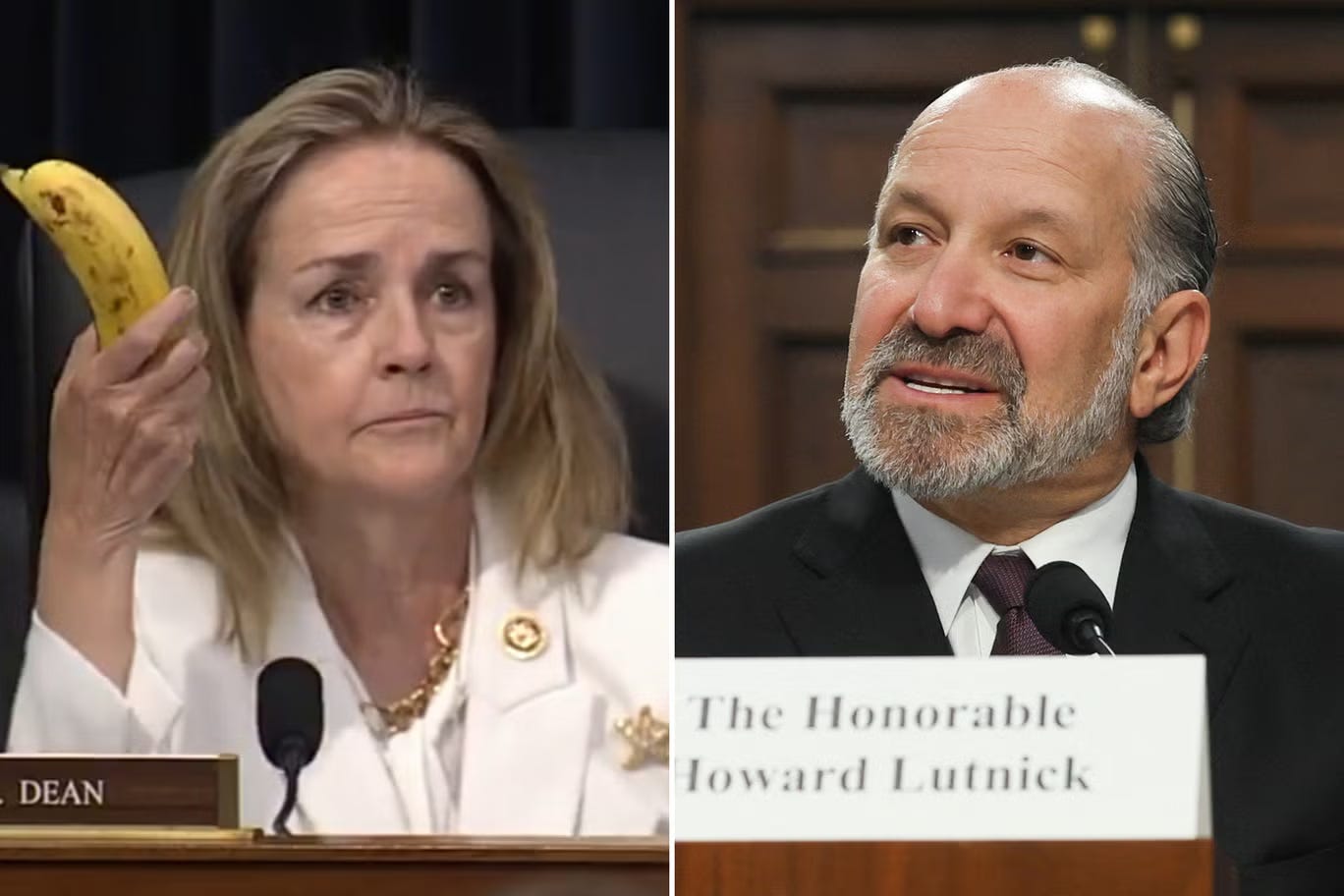

Last week’s House hearing on tariffs took a turn for the tropical when Rep. Madeleine Dean waved a banana in the air and delivered a message that somehow still needs saying in 2025: we cannot build bananas in America.

She was addressing Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, who had just suggested that the easiest way to avoid tariffs was for Americans to simply make everything at home. Bananas included, apparently.

Dean wasn’t buying it. She pointed out that grocery bills in her district are up by $2,000 a year, noting that Walmart had raised the price of bananas by 8%. When asked what the tariff on bananas was, Lutnick dodged before landing on “about 10 percent.” His recommendation? Bring production home.

Dean’s retort—we cannot build bananas in America—landed like a jab. But it also doubled as a pretty decent reminder of comparative advantage. You don’t need to take an introductory economics course to understand that sometimes it’s cheaper to let someone else grow your fruit.

A Quick Refresher on Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage is the idea that trade works best when everyone does what they’re relatively best at, even if someone else could produce the products you’re trading. The key is opportunity cost: what you give up to make something.

If it costs you less time, money, or resources to produce steel than it does to grow bananas, then you should stick to making steel and trading for your bananas. If every country specializes in the goods it can produce most efficiently, everyone benefits from lower prices and greater variety.

That’s why the U.S. imports bananas from countries like Ecuador, Guatemala, and Costa Rica. Those countries have the right combination of tropical climate, fertile soil, and affordable labor that makes banana farming relatively efficient. It also makes those products relatively inexpensive for us. Could the U.S. grow more bananas? Sure. But it would mean diverting farmland and workers away from crops we’re better at producing. But the payoff just isn’t worth the tradeoff. In other words, the opportunity cost would be too high.

Sources of Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage doesn’t just magically appear; it has to come from somewhere. Economists usually group different sources of comparative advantage into a few broad categories.

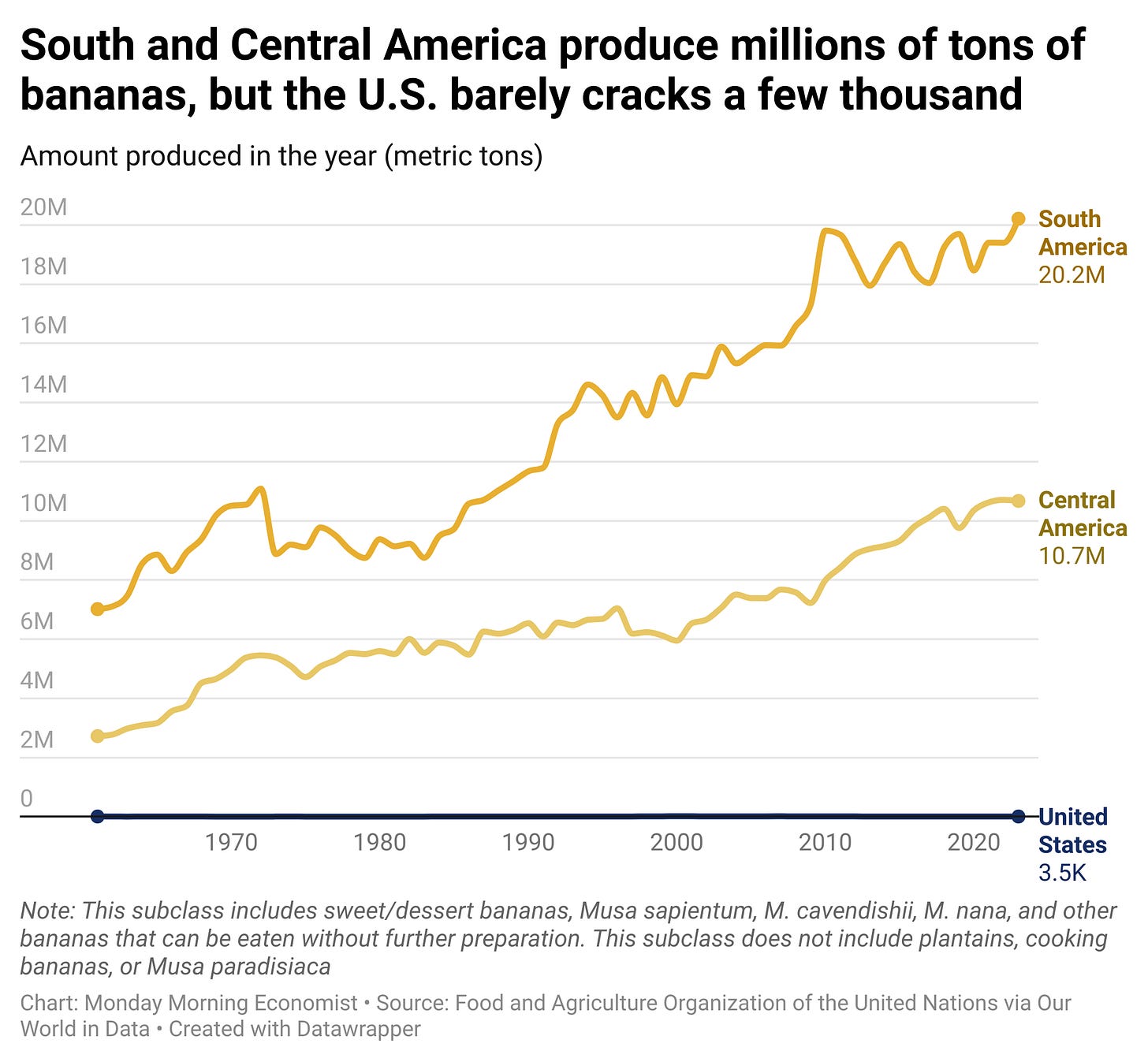

Some countries have a comparative advantage because of their geography and climate. For example, bananas grow best in hot, humid, tropical climates. Most of the continental U.S. doesn’t qualify. A few states, like Florida and Hawaii, grow some bananas, but not nearly enough to meet national demand. This would be a fairly stable source of comparative advantage that a country couldn’t easily build (or buy) its way into. Other examples include Saudi oil or Chilean copper. You either have it in the ground or you don’t.

The other sources are a bit different. They are the kinds of advantages countries can develop over time through investments in education, infrastructure, technology, and institutions. But the key word here is time. It can take decades, and it’s expensive. Think of South Korea’s electronics industry or Germany’s precision manufacturing. Those didn’t happen because someone passed a law or slapped on a tariff. They happened because of long-term public and private investment, sustained over the years.

That’s why arguments for bringing production back to the U.S. often sound simpler than they really are. Even if a country can eventually build a new comparative advantage, it’s not something that happens immediately. And even once you get there, trade still makes sense. No country can produce everything more efficiently than any other country.

The Limits of “Build in America”

The “build in America” argument has intuitive appeal. Who wouldn’t want to make more things at home, avoid supply chain disruptions, and be less reliant on other countries? But it misses the primary reason trade exists in the first place: efficiency.

The U.S. will always have a banana trade gap; we import more than we’ll ever export. But that’s because it’s not efficient for us to grow them. We don’t have the right climate, and trying to force domestic production through tariffs or subsidies just means higher grocery bills for everyone.

That’s the whole point of the trade system. A trade deficit in bananas, electronics, or sneakers isn’t a failure. It reflects the reality that some countries can produce certain goods more cheaply or effectively than we can, and vice versa.

Final Thoughts

Investing in domestic manufacturing isn’t a bad thing. In fact, public investment can play an important role in helping the U.S. develop comparative advantages in high-tech sectors, clean energy, or advanced materials. But that’s a budgetary decision, not something you can create with tariffs. Protectionism just locks in higher prices for products that could be made more efficiently elsewhere.

The United States doesn’t grow its own bananas because it shouldn’t, not because it can’t. The same is true for plenty of other goods we import. Trade deficits aren’t inherently bad; they’re a reflection of comparative advantage. And while reshoring may sound like a solution, it’s not always the most affordable one.

Sometimes, the best policy is knowing when to import the banana.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter examines the economic factors behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or buying me a cup of coffee!

The average American consumes nearly 27 pounds of bananas each year, which equates to about 90 bananas [ABC News]

In 2024, the United States imported $2.79 billion worth of bananas, with the main sources coming from Guatemala ($1.06 billion), Ecuador ($530 million), and Costa Rica ($438 million) [Observatory of Economic Complexity]

In 2023, the United States imported 11,225,409,281 pounds of bananas from around the world [World Bank]

There are approximately 318 acres of farmland in Hawaii dedicated to growing bananas [Hawai'i Department of Agriculture]

America’s trade surplus in services rose to $293 billion in 2024, up 5% from 2023 [CNN]

Minor quibble about your chart title: the US produces thousands *of tons* of bananas, not thousands of bananas

Thanks, Jadrian! The banana video made my week. Of course, now I'm in a downward spiral of ReasonTV music videos...