About those unemployed workers...

Unless you haven’t left your house or looked at the news in the past 18 months, you’ve realized there has been an ongoing labor shortage. Economists, policy wonks, and news pundits have spent a considerable amount of time trying to pin down why that’s the case. Earlier this year I pointed out that a lot of low-wage jobs, like fast food or retail, are pretty unpleasant experiences and that compensating differentials might be a plausible explanation for why we’re seeing a delay in workers heading back to these positions. A vocal rebuttal of that viewpoint preferred to talk about extended unemployment benefits as a potential cause for why low-wage workers weren’t coming back to work. The essential argument was that low-wage workers were earning more from unemployment than they were from work, so they don’t go to work. New research may say otherwise.

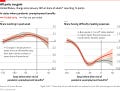

After a number of states have ended their supplemental benefits for the unemployed, and researchers have been able to compare those results to states that continued to pay more than the standard amount. Some pundits argued that ending the extra pay would force workers back into the labor market, thus “creating” more employment as shown in the monthly JOLT report. Spoiler alert: that’s not what happened. Instead, it appears that it just increased the share of people who experienced financial stress. Check out this incredible graphic produced by The Economist using data from the US Census Bureau:

On the left, we see that the share of people working is fairly consistent between early enders and those continuing to pay extended benefits. The horizontal axis looks at the number of days before/after a state ended their benefits (if they did) and is a technique referred to as difference-in-difference. Extended unemployment benefits were used as an incentive to stay home during the pandemic, but they also represent an opportunity cost of working. Going back to work meant not only giving up the unemployment checks but also those extra benefits provided during the pandemic. The smaller the opportunity cost, the more likely people are to do something, so theoretically, removing those benefits should incentivize people to go back to work. Realistically, that didn’t seem to be the case.

This behavior reminded me a lot of the issues of “free goods” that I read about a few years (more on that below). Traditionally, economic theory predicts that as prices decrease, people will want to consume more items. In the case of unemployment benefits, as the value of staying home decreases, they should go to work more. When it comes to buying products, this behavior is generally true for most price levels, but people start to behave differently around prices of zero. People treat free products differently than they treat products priced even slightly higher, perhaps because they don’t want to seem selfish when offered something free. It seems that a similar behavior happens with respect to employment decisions.

A recent study by a collection of authors finds that employment did increase slightly in states that cut off the extended benefit, but that doesn’t mean that things were necessarily better. Workers in those states also decreased spending, potentially offsetting the gains from employment. A secondary issue is that while people who were unemployed were more likely to be employed later, the total gains in employment (including those who weren’t collecting unemployment before) actually increased more in states that continued the extended benefits. This is similar to the results found last summer from a team of researchers at Yale. The general takeaway is similar to the zero price story, money (and prices) aren’t the only things factoring into behavior.

A more concerning result came from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, which recently started surveying tens of thousands of Americans regarding their spending habits during the pandemic. Respondents in states that cut off extended benefits early found an increase in the share of the population reporting that it was difficult to pay for typical household expenses. This is very similar to other research on the impact of social safety nets and universal basic income more broadly. Having that protection makes it easier to for workers to more accurately match with suitable employers, partly because the stress of day-to-day decisions is substantially lower. Consider this the employment version of “zero price” demand. Workers behave differently when they have zero income (no unemployment protection) and their behavior may not actually be good for the economy.

There are around 2.8 million “continued claims” for unemployment [US Employment and Training Administration]

Kansas was found to be the #1 state for extended unemployment benefits based on the cost of living, payout, and length of payout [Forbes]

27.6% of respondents said that they had experienced a somewhat or very difficult time paying for usual household expenses during the coronavirus pandemic [US Census Bureau]

The City of Stockton gave 125 people living below the city’s median income level $500 per month unconditionally in an attempt to study the impact of universal basic income [NPR]

Week 33 is over and I’m still at 50 books for the year. Classes start today and the past week has just been filled with anxiety. I’m in the middle of a few books, and I hope to hit the 52 mark later this week. To be honest, you likely won’t see a new check-in for a while. If you’d like to see what my labor economics students will be reading (or reading from), check out my bookshelves on Bookshop.

Instead, I’d like to recommend two books based on this week’s newsletter. If you found the idea of behavioral changes around zero prices interesting, check out Dan Ariely’s book, Predictably Irrational. If you’d like to learn more about universal basic income, I really enjoyed Annie Lowrey’s, Give People Money.