Ticketing Power Takes Center Stage

A lot of people are talking about Ticketmaster recently, but their market power on buying and selling ticket will likely result in some talks at the Department of Justice as well.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of over 2,800 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

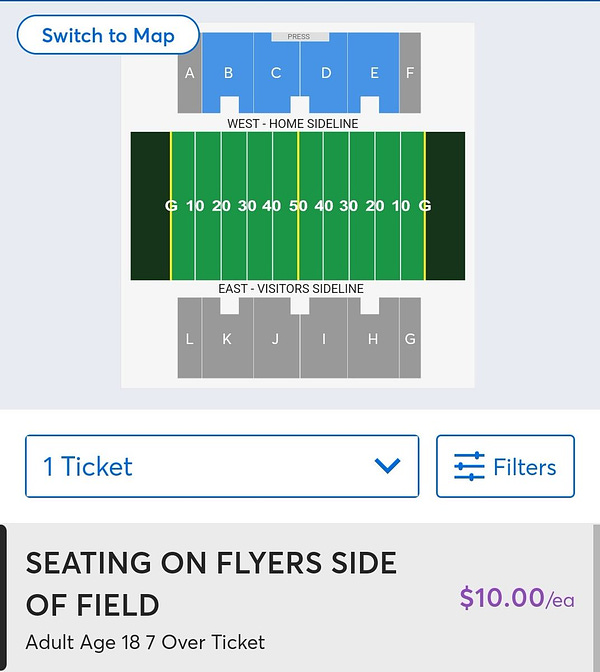

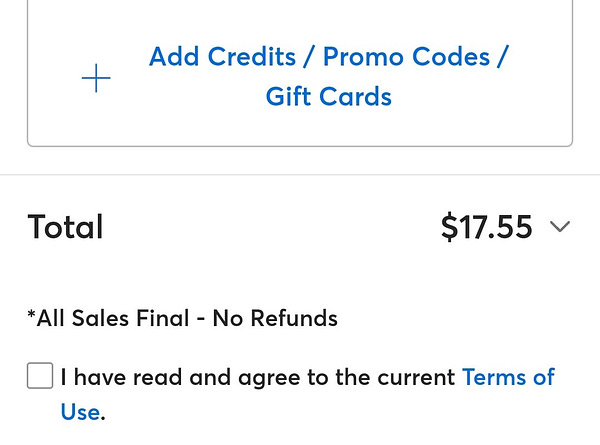

I’m not sure I’ve ever met anyone who loves Ticketmaster. At best, their feelings are likely neutral. I imagine that comes from rarely buying tickets for concerts or sporting events. The last time I wanted to purchase tickets for a football game, the tickets were sold online through Ticketmaster. A general admission ticket for the Dayton Flyers would have set me back $10, but once I got to the checkout the total came to $17.55 after taxes and fees:

I did not buy my ticket through Ticketmaster that day. I waited until gameday, drove up to the stadium, and stood in line at the box office. My total price came to exactly $10 for a general admission ticket. There were no added service fees, taxes were included in the total, and I got a paper ticket instead of a digital one. This alternative only really works when the venue isn’t sold out.

For that game, Ticketmaster was competing directly with the stadium box office, and the box office won my business based on price. But what about events where you want to pick a specific section or the ones that are in really high demand? Waiting to buy your ticket at the box office may mean that your preferred section is sold out, or worse, the entire venue is sold out. There is a great episode of The Simpsons where Homer waits in line for 8 days to get tickets to an event, only to lose out to a scalper who buys all of them:

If you decide to wait and buy your tickets at the box office to avoid the fees, other fans are scooping up tickets on Ticketmaster. They aren’t as sensitive to prices or they may be planning to sell some of them on the secondary market at higher prices. If the event is popular enough, there’s little chance you’ll secure a seat at face value on the day of the show. Your only real options are to purchase from Ticketmaster or wait for tickets on the secondary market. Some Taylor Swift fans learned about Ticketmaster’s monopoly power while trying to secure coveted tickets to her first concert series since 2018. It turns out though that Ticketmaster holds a coveted position of being both a monopolist and monopsonist.

Ticketmaster as a monopoly

The most straightforward side of the story is to view Ticketmaster's position as a ticket seller first. While Ticketmaster faced some competition with the Dayton Flyers box office for my business, Taylor Swift fans didn’t really have an alternative method of buying tickets when they first went on sale. If they missed out on the initial ones, they’ll need to wait for the secondary market. As a quick aside, Ticketmaster also operates in this space as well, but they face a little more competition from sites like Stubhub and Seatgeek.

Monopoly power is based on a firm’s ability to block competitors from selling the same product. These barriers to entry enable firms to reduce the number of close substitutes for the final buyers and then charge those buyers a markup above the cost of providing the service. The cost of issuing a single digital ticket to the Dayton Flyers football game isn’t zero, but it’s probably less than $7.50. Those additional fees are likely part of the firm’s monopoly markup, which bases the final price as a percentage of the cost of providing an additional product.

Firms could set those fees as a fixed fee regardless of the ticket price, but that would likely only work if firms are competing with others. Ticketmaster’s fees actually increase as the ticket price increases. Here’s a snippet from Ticketmaster’s website about their fees and charges:

In some instances, events on our platform may have tickets that are “market-priced,” so ticket and fee prices may adjust over time based on demand. This is similar to how airline tickets and hotel rooms are sold and is commonly referred to as “Dynamic Pricing."

Ticket prices could be priced based on supply and demand, but it’s strange to assume that there is any demand for those accompanying fees. As long as people are willing to pay more for tickets, Ticketmaster happily adjusts their fees upward as well. Issuing a digital ticket doesn’t cost Ticketmaster more because are willing to pay for a ticket. That’s the power of monopolies.

Even if we look at the secondary market, there are still only a few major competitors with Ticketmaster. This is likely due to a different barrier to entry known as economies of scale. There are a considerable amount of fixed costs associated with setting up an exchange board and managing that exchange. Those costs are largely incurred before a single ticket is sold, but Ticketmaster can lower the average cost of providing the service if they are able to capture a large portion of that market. It wouldn’t be profitable to set up this service if only 10-20 people were reselling tickets, but the cost falls dramatically if they’re reselling 10-20 thousand tickets.

Economies of scale are one of the common barriers to entry for oligopolistic markets. These markets operate similarly to monopoly markets, but there are a few companies selling similar services. These companies have some market power and are able to charge prices that are higher than the cost of providing the service to another person, but that power is not nearly as strong as if they were the only one. In the secondary market, Ticketmaster (and others) also charge service fees to both buyers and sellers who would like to exchange their tickets.

Ticketmaster as a monopsony

Ticketmaster has monopoly power on selling tickets because they control a scarce resource, but they also hold some market power over the artists. There are a limited number of ticketing companies that artists can work with to sell tickets to their events. Ticketmaster operates as a monopoly provider of tickets to concert-goers, but they operate as a monopsonist for artists looking to tour the country.

A monopsony market contains only one buyer of a product, rather than a monopoly market in which there is only one seller of a product. Monopsonistic markets have only a few buyers, which gives them the power to push prices down for the goods and services they are buying. Since there is only one major buyer of performance services, artists don’t make as much as they would under a more competitive structure.

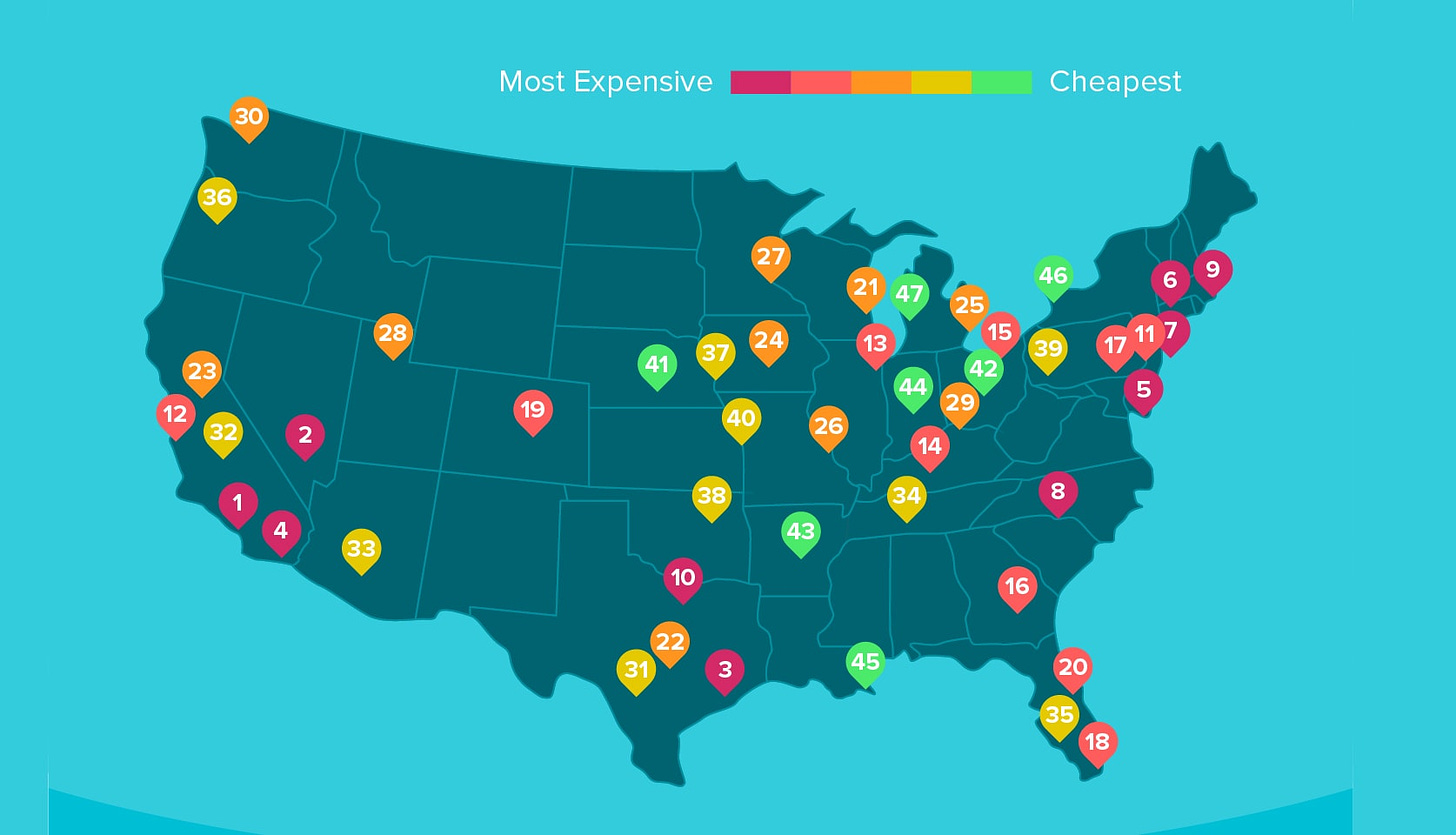

For smaller events, like the Dayton Flyers football program, the monopsony power is relatively limited because the athletic department could find a new provider or just sell tickets at the box office. For an artist like Taylor Swift, however, her tour is only stopping at the largest stadiums in the United States. Those stadiums have exclusive partnerships with Ticketmaster to serve as their primary ticket seller. If an artist wants to perform at that stadium, their only option is to use Ticketmaster as the intermediary.

To make the situation even worse, Ticketmaster merged with the nation’s largest promotion company, Live Nation, back in 2010. Here are some of the stats for the two companies, reported by The New York Times back then:

Ticketmaster has roughly 70 percent of the concert ticket market in the United States and is known for the ever-rising cost of an assortment of tacked-on fees, now as much a part of concert experience as sticky floors and shoving. Live Nation, led by Michael Rapino, 43, is a roll-up of regional promoters that now runs more than 22,000 events a year, many in the 127 amphitheaters and clubs that the company owns or operates. Total annual attendance is more than 50 million.

This monopsony power over performers is part of the reason that Ticketmaster has monopoly power on selling tickets. Live Nation manages a lot of artists (and venues), who only work with Ticketmaster, which lowers the artists’ overall earnings and raises Ticketmaster’s profits. That’s their monopsony power. With Ticketmaster having the exclusive right to sell the initial tickets, they control a scarce resource and raise prices for consumers. That’s their monopoly power.

The Justice Department approved the merger back in 2010, but politicians have been asking for it to be reevaluated even before the Taylor Swift debacle. Perhaps this may be the event that pushes the needle to start that process. Representative Ocasio-Cortez seems to think so:

Ticketmaster reported an adjusted operating income of $209 million for the first quarter of 2022 [Ticketmaster]

Ticketmaster sold an estimated 111,292,000 tickets in the first quarter of 2022 [Tickermaster]

Over 2 million tickets were sold on Ticketmaster for Taylor Swift | The Eras Tour on Nov. 15 – the most tickets ever sold for an artist in a single day [Ticketmaster]

Live Nation operates 160 venues around the world and promotes over 500 artists [Live Nation]