The Big Car Dilemma

Why do Americans keep buying bigger cars, even when it's killing them?

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 5,400 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

Americans love big cars. Once the domain of contractors and off-road adventurers, pickup trucks and SUVs now dominate suburban driveways and city streets. What used to be a practical choice for the rugged outdoors has become the go-to option for families and commuters alike. The appeal is obvious: more space, more power, and, most importantly, a sense of safety.

But here’s the catch—what feels like a smart, personal decision to protect your family may actually be making the roads more dangerous for everyone else. A new study on vehicle size and fatalities reveals a troubling reality: the bigger the car, the deadlier the consequences for others on the road. It’s a textbook example of how well-intentioned private choices can lead to harmful public outcomes—what economists call negative externalities.

Bigger Is (Sometimes) Better

When buying a car, people tend to focus on private benefits—things like safety, comfort, and utility. And for many, safety is the top priority. Parents, in particular, are drawn to the idea that a bigger, heavier vehicle means better protection in an accident. And in a sense, they’re right. The statistics show you’re more likely to walk away from a crash unscathed if you’re driving a pickup truck or SUV than if you’re behind the wheel of a smaller sedan. The extra weight acts like a buffer, absorbing much of the impact.

But safety isn’t the only reason Americans love big vehicles. Trucks and SUVs come with a laundry list of other perks—more space for the family, room for pets, and the ability to haul just about anything. They can tow boats, trailers, or furniture for a weekend move. In rural and suburban areas, they feel like a necessity. Whether it’s winter weather or rough roads, four-wheel-drive trucks and SUVs offer a sense of control and capability that smaller cars simply don’t.

These are real, tangible benefits for the person behind the wheel. It’s easy to see why the market for large vehicles continues to expand. But the key here is that these private benefits don’t tell the whole story. The costs of driving a big vehicle aren’t just felt by the driver—everyone else on the road pays a price too.

The External Costs of Big Cars

But here’s where the problem comes in: the very thing that makes large vehicles safer for their occupants—size—makes them much more dangerous for everyone else. It’s simple physics. When a heavy SUV or pickup collides with a smaller car, the smaller car is at a serious disadvantage. A new study published in The Economist shows that the fatality rate for drivers in smaller cars skyrockets when they’re hit by a much heavier vehicle.

And it’s not just other drivers who bear the cost. Pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists are particularly vulnerable. Trucks and SUVs sit higher off the ground, and their sheer bulk often reduces the driver’s visibility, making it harder to spot people crossing the street or biking alongside them. When a crash does occur, the force of a 7,000-pound vehicle hitting a person is devastating—far worse than being struck by a smaller, lighter car.

This is a textbook case of negative externalities—costs that aren’t directly felt by the person making the decision but are instead imposed on others. When someone buys a large vehicle, they’re making a private decision to protect their own family. But that decision makes the road more dangerous for everyone else—whether it’s other drivers or people on foot. It’s a trade-off that, while optimal for the individual, creates more harm than good for society as a whole.

From a public health perspective, the ideal scenario would likely look much different. If we could redesign the roads to maximize safety for everyone, we’d likely see fewer massive trucks and SUVs. Instead, roads would be filled with mid-sized cars—offering enough protection for occupants but without the outsized risks posed by the heavier vehicles. But here’s the catch: we don’t live in a world where people coordinate their vehicle choices. Instead, we’re trapped in what economists call a prisoner’s dilemma.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma of Vehicle Choice

In its simplest form, the prisoner’s dilemma is a situation where individuals act in their own self-interest, but end up with worse outcomes than if they had worked together. Imagine two criminals who have been caught by the police—if they both stay silent, they get light sentences. But if one betrays the other, they get off free while the other faces the consequences. Since they can’t trust each other, both betray, and they both end up worse off.

Now, think about America’s roads. As more people see trucks and SUVs around them, they rationally decide the best way to protect themselves is to buy a bigger vehicle too. But the more people make this choice, the more dangerous the roads become. In the end, the very thing that was meant to make us safer—buying bigger cars—makes us collectively less safe. If we all drove smaller cars, road fatalities and injuries would likely drop. But the individual decision to prioritize personal safety leads to a collective outcome where we’re all at greater risk. It’s a classic prisoner’s dilemma—what’s good for the individual makes things worse for society.

Final Thoughts

Escaping this trap isn’t simple. Car buyers are motivated by powerful incentives to prioritize safety and comfort, and automakers are more than willing to meet that demand. Complicating matters further, U.S. regulations actually encourage the production of SUVs. The current regulatory framework, which defines SUVs based on their size and shape, makes it easier for automakers to design and sell larger vehicles. Even the shift to electric vehicles, though positive for the environment, has resulted in heavier cars due to the weight of their batteries. The system, as it stands, reinforces the cycle of bigger vehicles dominating the roads.

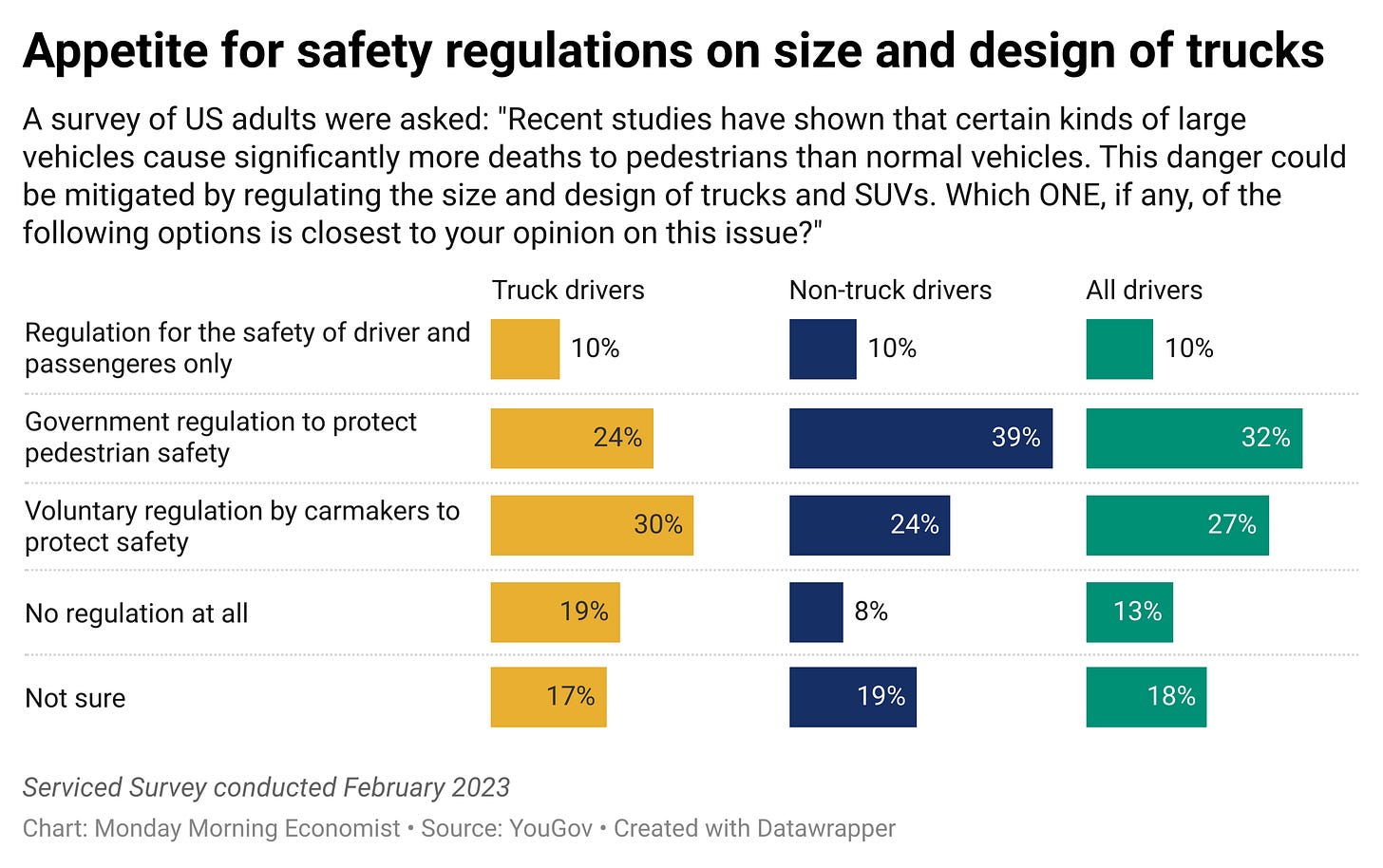

Economists offer a few common solutions to address negative externalities: taxes, regulation, and cap-and-trade systems. For instance, the government could impose higher taxes on heavier vehicles, making smaller cars a more attractive option financially. Stricter fuel-efficiency regulations could push automakers to build lighter vehicles or make larger ones safer for others on the road. Although hard to imagine in the automotive industry, a cap-and-trade system could theoretically limit the number of heavy vehicles by allowing manufacturers to trade production permits based on vehicle weight.

These policy options could help tip the scales toward a more balanced and safer road environment. Each approach has its challenges—taxes would likely meet public resistance, regulations could be seen as restricting personal freedom, and cap-and-trade could be tricky to implement—but these are potential pathways to balance individual preferences with societal safety.

At the core of this issue is the tension between individual choices and collective well-being. People understandably want to protect their families, which often means choosing bigger vehicles. But these choices impose real costs on others, from higher fatality rates to more dangerous roads for pedestrians and cyclists. It’s a collective challenge, and tackling it will require both personal reflection and policy innovation. In the end, the solution isn’t just about changing what we drive, but how we think about the impact of our choices on others.

Not a subscriber? Sign up for free below!

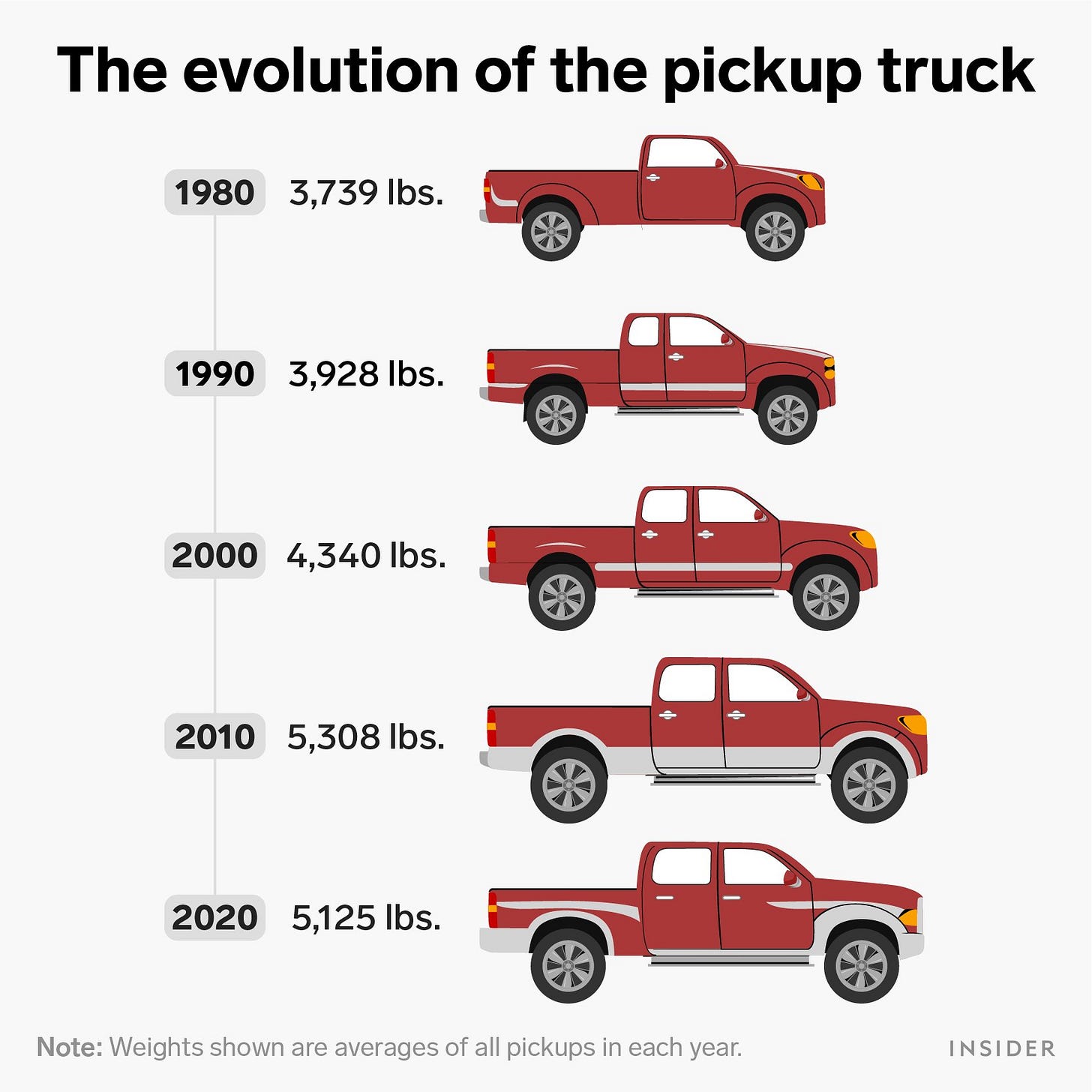

Over the past 30 years, the average U.S. passenger vehicle has gotten about 4 inches wider, 10 inches longer, 8 inches taller, and 1,000 pounds heavier [Insurance Institute for Highway Safety]

The average new car in America weighs more than 4,400 pounds, compared with 3,300 pounds in the European Union and 2,600 pounds in Japan [The Economist]

The best-selling vehicles so far in 2024 are the Ford F-Series and Chevrolet Silverado trucks [Kelley Blue Book]

32% of Americans believe that the government should step in and impose regulations, including a significant portion (24%) of truck drivers [YouGov]

The median annual household income in the US was $67,521 in 2020. For SUV owners it was $97,082 and for truck owners it was $108,334 [Business Insider]

Very interesting. One reason it may not happen in Europe as much is that policy regulations tend to be less car-friendly, with higher taxes on petrol and limitations on car traffic in downtown areas.

I posted that recently about Paris: https://x.com/page_eco/status/1832746075247227125

Smaller cars could be made more safe, but that would add weight, and they're hamstrung by fuel efficiency regulations. "Safe, small cars" have been effectively regulated out of possibility.