Tariffs Are Costly Options

Some are celebrating record-breaking tariff revenue as a win for U.S. trade policy. But as the data and business leaders make clear, this is a trade TACO

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

The U.S. just pulled in a record $22.3 billion in tariff revenue in May 2025. That’s the highest monthly total ever. If you’re looking at that news alongside the previous month’s inflation numbers, you might be thinking that tariffs are doing what the administration said they would do.

Revenue’s up. Inflation rates are coming down. So, what’s the problem?

Well... maybe everything.

What appears to be a win for trade policy might actually be a warning sign. Yes, tariff revenue hit a record, but imports are way down. According to the most recent data, U.S. imports fell by 19.8% this April compared to just a month earlier. Yes, that’s a record, too.

So where’s all that revenue coming from? It’s not from volume, it’s from price. Companies are now paying more to bring in less. Some are absorbing those higher costs, others are passing them on. Either way, that money has to come from somewhere, whether it’s a company holding off on a new product launch or a family skipping a vacation.

In other words, we’re not trading more. We’re just spending more to trade less.

What Mark Cuban Gets Right

Over the weekend, investor Mark Cuban posted a tweet that captured something that media commentators have been puzzling over for the past months: why haven’t prices gone up yet?

Cuban’s explanation starts with inventory. Companies didn’t just wait around when they heard tariffs were coming, they rushed to import as much as they could before the tariffs went into place. That meant sending huge amounts of cash overseas, long before those goods ever hit the shelves.

But now companies are sitting on mountains of inventory, hoping they guessed right about what to buy and when. Consumers likely did the same thing, but are now pulling back on purchases. Some businesses are forced to cut prices just to move product and recover cash. But those cuts aren’t permanent.

Walmart and Target have both warned that price increases are coming. Their hands are tied by the same pressure: unpredictable trade policy, ballooning inventory, and the financial stress of floating tariff payments while trying to look calm on the outside.

The Real Cost: What You Don’t See

It’s a classic case of opportunity cost, the idea that every decision comes with a trade-off. Cuban was blunt about this: cash isn’t free. When businesses spend millions stockpiling inventory or paying interest on short-term loans, it’s money that could have gone toward hiring workers, developing new products, or investing in more efficient operations. Instead, it’s sitting in warehouses or going to banks.

The same thing happens with tariffs. That record-breaking revenue the government just collected? It didn’t appear out of nowhere. Companies paid it as the new price of doing business. That’s cash they can’t spend elsewhere, whether that’s upgrading equipment or growing their teams.

Consumers did the same thing. When tariffs were announced, many people rushed to buy big-ticket items before prices had a chance to jump. Now, analysts think that early spending may be turning into a pullback, as households brace for what comes next.

If prices go up, families will have to cut back even more. Maybe that means skipping a vacation, holding off on home repairs, or delaying a new phone upgrade. Just like companies, consumers are adjusting. It’s not because they want to, but because they have to.

The Deadweight Loss Triangle, in Real Life

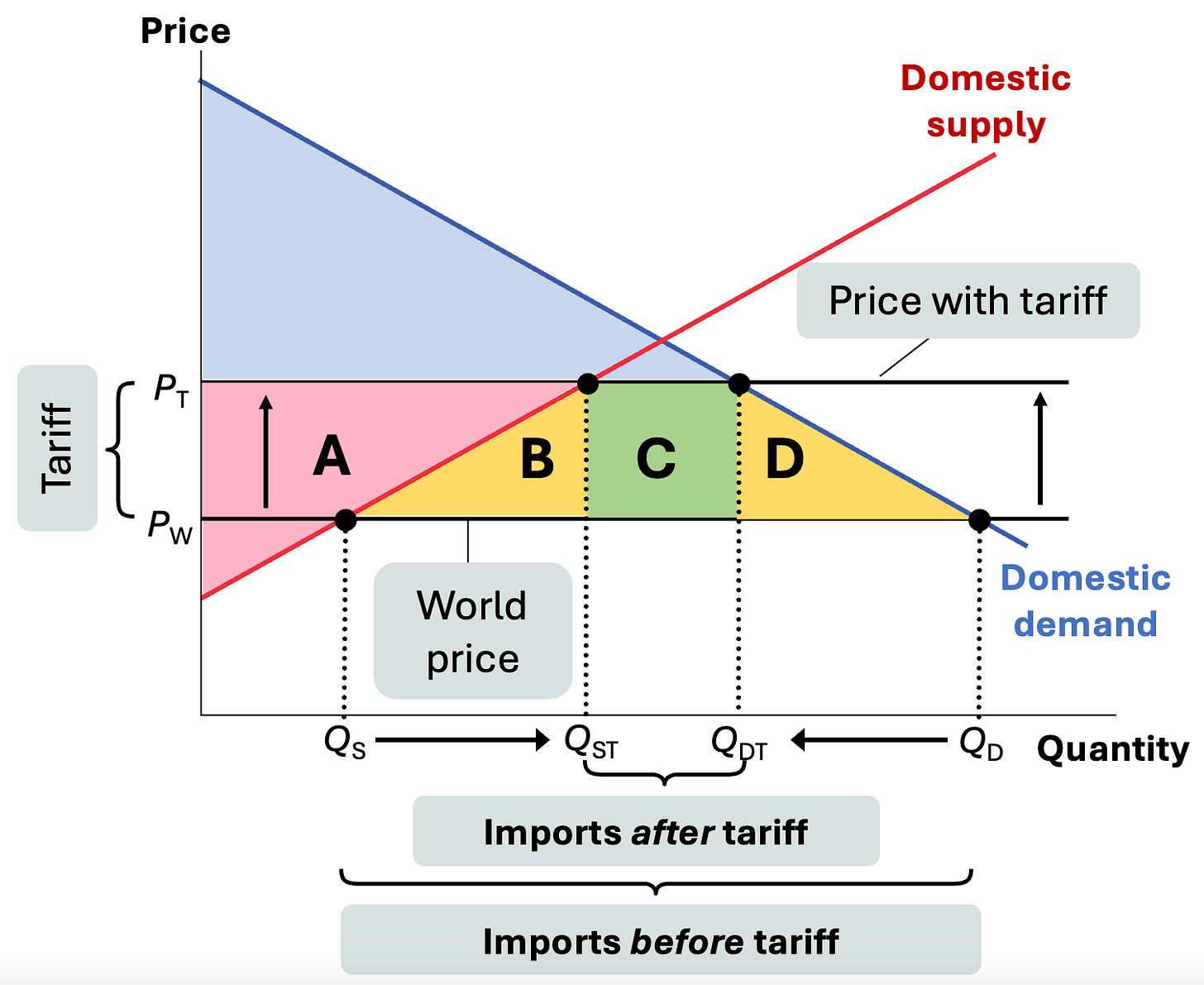

If you’ve taken an intro economics course, you might remember the classic tariff graph. If you haven’t, don’t worry. You don’t need to read the graph to understand the idea behind it. I’ll provide a graph below from my principles courses to help tell our story.

There are a lot of moving parts in this graph, but we want to focus on the two yellow triangles that represent something economists call deadweight loss. It’s a measure of the value that disappears from society when trade is restricted. Think of them as two different kinds of economic waste.

Let’s start with the triangle labeled D in the chart above. That’s a measure of the loss that comes from people buying less because prices have gone up. And we’re likely seeing this play out in real time. In April, U.S. goods imports fell by $68 billion, a sharp drop as businesses and consumers pulled back on spending on higher-priced imports. This is a value that has disappeared from the economy. It’s trade that used to happen, but doesn’t anymore, because the price is no longer worth it.

The second triangle, labeled B, is a little harder to spot in everyday life because it’s about opportunity cost. It reflects what we lose when production shifts from more efficient foreign producers to less efficient domestic ones. At first, that might sound like a win—more things made in America, more jobs at home. But there’s a catch.

It will take more resources to make the same product domestically, but those resources don’t appear out of thin air. If we use them to produce goods we used to import more cheaply, that means we have less capacity to make other things. We’ll have fewer workers available for industries where the U.S. has a real advantage. Tariffs don’t expand our country’s productive power; they rearrange it in less efficient ways.

And that brings us back to Mark Cuban. When companies tie up cash in inventory, they’re reallocating the time, money, and talent that could have gone toward growth. Consumers aren’t just losing access to cheaper goods. We’re using our resources in ways that are less productive, just to manage the uncertainty.

The cost of tariffs isn’t just what shows up at the register. It’s everything we don’t get. It’s the products not launched, the jobs not created, the progress that gets paused.

Final Thoughts

Let’s go back to the headline we started with: $23 billion in tariff revenue collected last month. On the surface, it sounds like a windfall. Some politicians have even suggested tariffs could take the place of income taxes. But the math doesn’t work. It’s not even close.

The federal government collects more than $2.4 trillion each year in individual income taxes. Even with May’s record-setting performance, the tariff revenue we’ve collected so far covers less than 3% of that total. We’re almost halfway done with the year, and the tariff revenue won’t increase at a pace to fill that void.

Here’s the other problem: imports are falling. U.S. goods imports dropped sharply in April, and if that trend continues, tariff revenue will fall with it. After all, that’s how tariffs are designed to work. They’re meant to discourage imports, and if they succeed, they shrink their own tax source.

This is the paradox: the better tariffs “work,” the less money they bring in.

Tariffs should be policy levers, not profit centers. They aren’t built to fund the government, they’re built to change behavior. Relying on them for revenue is like trying to replace your salary with a garage sale. You might make a lot in the first week, but eventually, you run out of stuff to sell.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter examines the economic factors behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

The United States has generated $68.6 billion this year from tariffs as of May 29, the latest data available—77.8% more than the same time last year [Politico]

Tariff revenue was $77 billion in fiscal year 2024, representing 1.57% of total federal revenue [U.S. Congress]

The international trade deficit was $87.6 billion in April, down $74.6 billion from $162.3 billion in March [U.S. Census Bureau]

In fiscal year 2024, the U.S. federal government collected approximately $5 trillion in revenue [Bipartisan Policy Center]

I work for a large retailer in sourcing and this could not be more true of our daily lives. Inventory is bought in bulk at a “lower” tariff, canceled, moved to different seasons. Costs are increasing, retails are going up, and categories are getting cut from stores for being too expensive. Very well done article explaining the realities of tariffs!

My very first thought upon opening today's post was "man, I wish people understood deadweight loss", and then, later in the article, BAM, a whole thing about DWL. Beautiful.

"In other words, we’re not trading more. We’re just spending more to trade less." Very well said.