Why Your Loan Balance Isn’t Going Down, Even When You’re Paying A Lot

A viral crash out offers a chance to understand how student loans can grow faster than most borrowers expect, and what we can do to prevent it.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

A TikTok posted by a frustrated recent college grad named Alyssa went viral a few weeks ago. She shared how she was paying $1,500 each month on her student loans for the past two years, but somehow owes more now than when she started paying. Her current balance? $90,000.

She’s emotional. She feels stuck. And like a lot of recent grads, she thought she was doing everything right. I edited the video below to remove strong language, but kept her emotion intact.

When I first saw this on my feed, the 17% interest rate caught my attention. That’s much higher than most federal student loans. In an interview with People, Alyssa shared that she borrowed around $8,000 per semester during 5½ years of college. In total, she would borrow about $85,000 from a private lender. She made small payments of about $100 while in school. Unfortunately, those payments weren’t enough to keep her balance from growing.

What she’s describing isn’t unusual. And this post isn’t intended to be a criticism of her. My hope (and I think hers, too) is that this is a wake-up call for the next wave of borrowers.

Why Student Loans Are So Different

College in the U.S. can be expensive, sometimes shockingly so. Tuition alone can run into the tens of thousands of dollars per year at public universities. Private schools often cost even more. Add housing, food, and textbooks, and it’s easy to see why many students and their families turn to loans.

But student loans aren’t like car loans or mortgages. With those, lenders can repossess the asset if you stop paying. That makes them less risky and keeps interest rates lower. Education doesn’t work that way.

Once you’ve earned a degree, there’s nothing a lender can take back. They can’t repossess knowledge. That makes student loans riskier for lenders, especially private ones that don’t have federal backing.

To cover that risk, private lenders charge higher interest rates. Sometimes much higher. That’s how a borrower like Alyssa wound up with a loan that had a 17% interest rate.

How Her $85,000 Loan Became $95,000

According to her interview, Alyssa borrowed about $85,000 in student loans to study psychology at D’Youville University in Buffalo, N.Y. When it was time to start paying her loans, she likely owed closer to $95,000.

Why the difference? Because interest didn’t wait for her graduation.

She made $100 monthly payments while in school, but that doesn’t even cover the interest on her very first payment. The unpaid interest likely got added to the balance and started racking up interest on its own. That’s how compounding interest works.

She probably thought she was keeping up. Behind the scenes, her obligation was quietly getting larger. Here’s a simple example from her first year of college. If she borrowed $8,000 at a 17% interest rate, but only made $100 monthly payments, her balance would slowly increase each month.

But that table just shows the interest that accumulates on the loan from her first semester. She said she borrowed $8,000 every semester for more than five years. Her $100 payments were only chipping away at the interest on her first loan. It wouldn’t have made any difference in the later ones.

And that’s how someone who borrows $85,000 can start repayment owing significantly more. It’s also why someone can feel completely blindsided when what seems like aggressive monthly payments barely make a dent in the balance.

Why Didn’t $1,500 a Month Make a Bigger Dent?

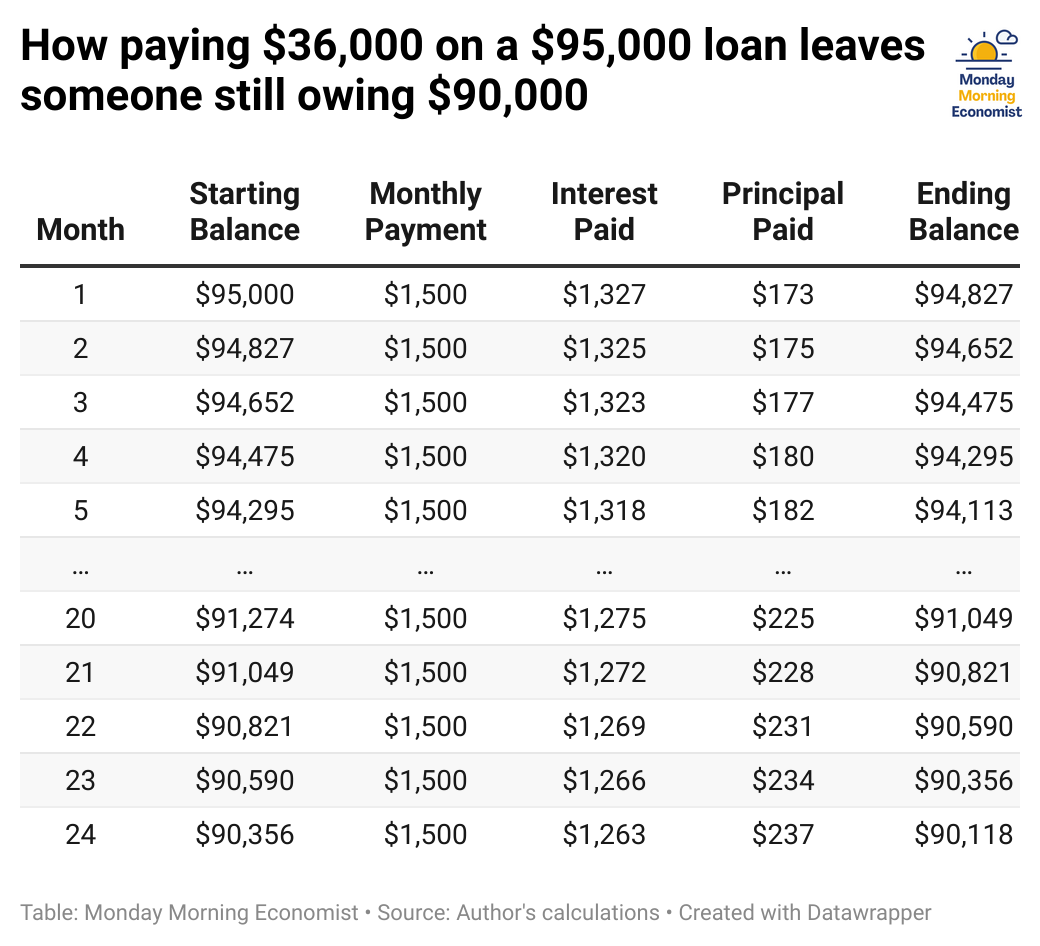

If Alyssa were paying $1,500 each month for two years, that would total $36,000 since graduation! So why does she still owe nearly as much as when she started?

Because interest eats first.

Loans are typically paid off through a process called amortization, which means you repay a fixed amount each month over time until the balance is paid off. Those payments are split into two parts:

Interest: This is the cost of borrowing money.

Principal: This is what reduces your remaining balance.

With a loan this size and a 17% interest rate, nearly 90% of each of her payments was going toward interest in the early months. As a result, only a small sliver of her payments was touching the loan balance.

Here’s what that looks like for the first few months and the last few months of a two year window:

After five months of consistent $1,500 payments, Alyssa would have sent her lender $7,500, but shaved less than $1,000 off her balance. On paper, that’s just how amortization works. Emotionally, it probably felt like she was setting money on fire.

But how long would she need to keep making those $1,500 monthly payments to pay off her loan? It would take more than 13 years, and she’d pay more than $138,000 in interest alone!

Can She Pay This Off Faster?

The fastest way to make a dent in a loan like this? Refinance. If she has a high enough income and a good credit score, she would likely qualify for a much lower interest rate. Refinancing from 17% to even 9% could cut years off her loan and save tens of thousands in interest. If that isn’t an option, the next best strategy is to find a way to make additional payments.

Loan payments are front-loaded with interest. The more she can chip away at the principal, the faster the balance falls. One popular method is making bi-weekly payments. Instead of paying $1,500 once a month, she would pay $750 every other week. By making 26 payments during the year, it’s equivalent to making an entire extra monthly payment.

Of course, there’s a catch. Many lenders don’t always apply extra payments to your balance by default. Often, they will count the payments toward your next bill. To actually reduce your principal, you’ll need to tell your loan servicer to apply any extra payments to the principal only. That setting may be buried in your online account or require a phone call.

One last thing to consider: if you overpay one month and come up short the next, those earlier overpayments usually won’t cover the gap. So, only use this strategy if your budget allows for consistency.

Final Thoughts

In a follow-up post, Alyssa asked: “Why would anyone give a 17-year-old a loan for college?”

It’s a fair question. Most of us made financial decisions at 17 or 18 without fully understanding the long-term costs. Even if she wasn’t required to take a personal finance course, the concept was probably taught in a math class on compound interest or exponential growth. But like most things we learned in school, it didn’t seem important until there was a bill due.

Some may argue that her parents should have taught her about this. But surveys find that parents consider teaching their kids about money as one of the most difficult life skills to impart. For first-generation students, it may never come up at all.

So no, I don’t think we should blame the 17-year-old version of Alyssa for her current situation. But I do think this is exactly why we need to teach the concept better and talk about it more often. The reality is that college can be expensive. And when you’re 18, it’s hard to imagine how a small loan becomes a monthly bill that competes with rent, groceries, insurance, and everything else adulthood throws your way.

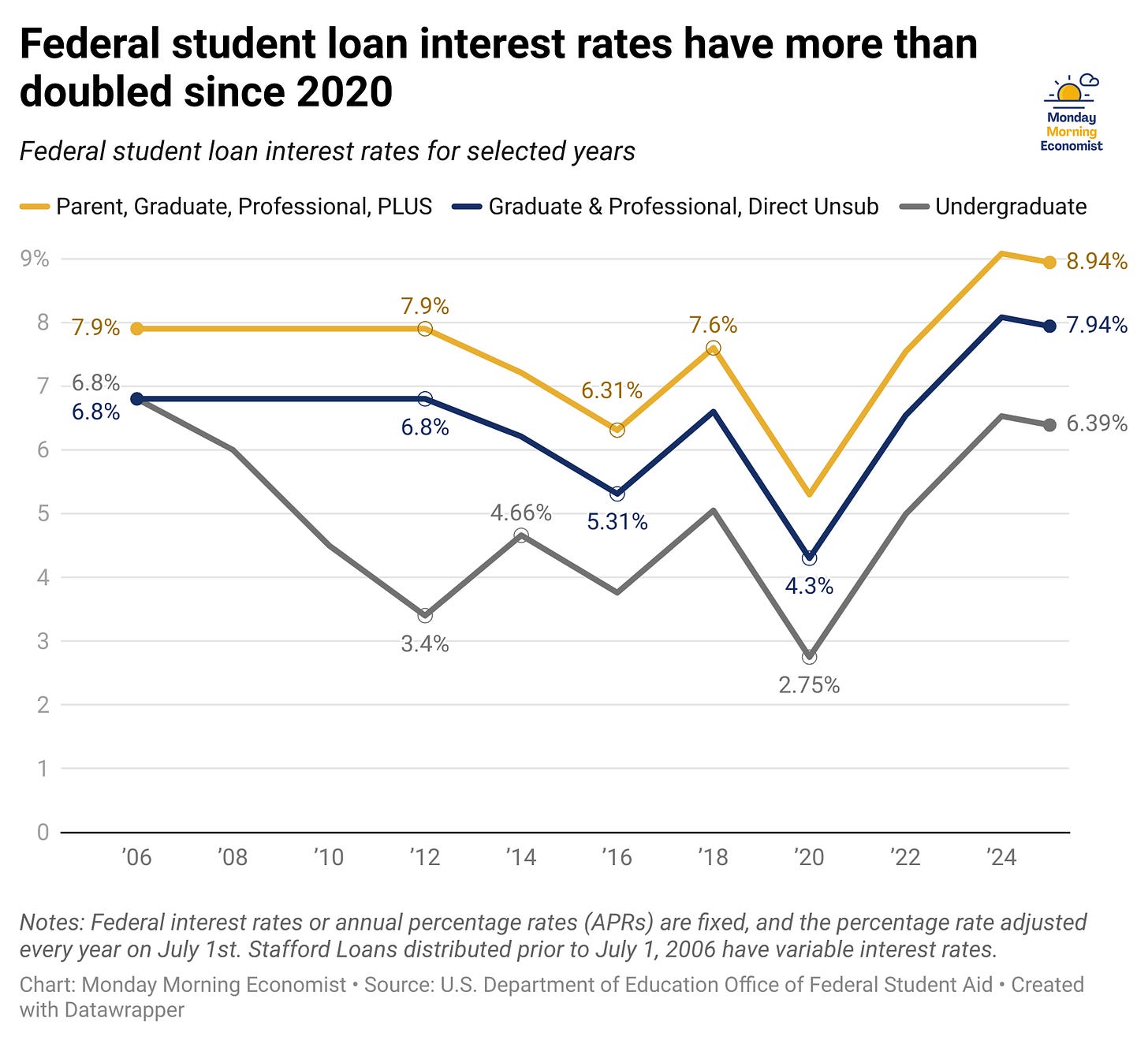

We should also be having real conversations about whether 17% interest rates on student loans are ever justifiable, and what role private lenders should play in financing education. But while that debate continues, the best thing we can do is help the next group of borrowers understand what they’re signing up for.

Know someone about to take out a student loan? Forward this to a high school senior, college freshman, or family member who’s thinking about how to pay for college. Understanding how interest works before the loan paperwork is signed can make a world of difference.

More than a million Americans owe at least $200,000 in federal student loan debt [CNBC]

In a survey of U.S. college students, 33% of respondents said their biggest post-graduation fear was student loan debt [WalletHub]

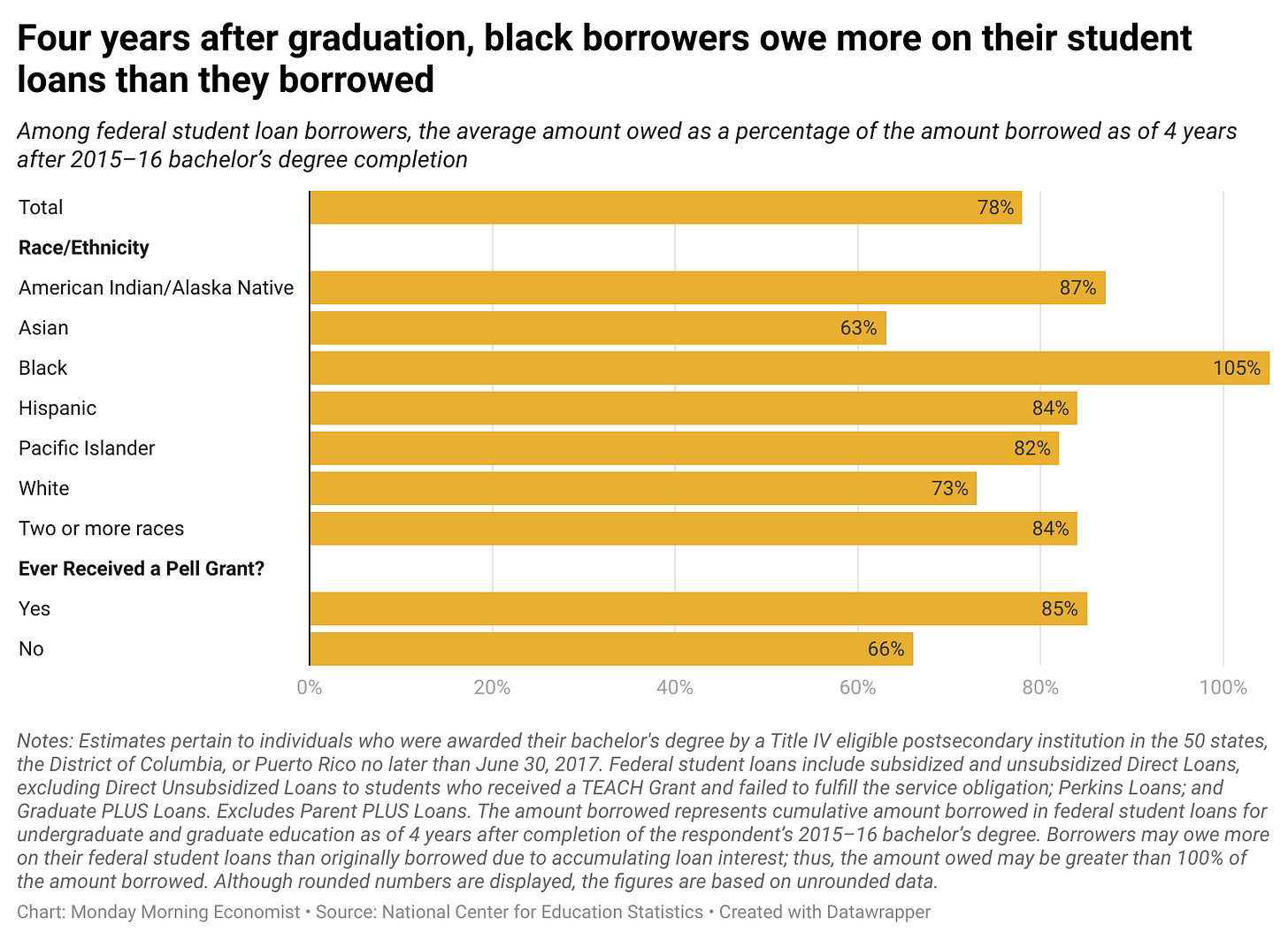

Four years after graduation, 48% of Black student borrowers and 17% of White student borrowers owe more than they initially borrowed [Education Data Initiative]

For students who completed their bachelor’s degrees during the 2015–2016 academic year and received federal student loans, the average amount borrowed as of 2020 was $45,300 [National Center for Education Statistics]

51% of Americans support the federal government cancelling $10,000 in federal student loan debt for each borrower whose annual household income is below $100,000 [YouGov]

Great post. When I first started teaching financial literacy after years in the mortgage industry, I was surprised by how many people didn’t understand interest and how it accrues.

It always makes me anxious to see young people taking these loans without being properly informed, Both students and parents need much better financial education before signing anything.