Student Loans: What Are They Good For?

The conversation around student loan forgiveness has increased over the past few weeks and President Biden is reportedly considering a $10,000 forgiveness for certain borrowers. Last week, The Flip Side had good coverage of what newspapers on the left and right were saying about the announcement. This week’s post isn’t on the economic impact of debt forgiveness, but rather on the economic purpose of student loans. If you’re curious about the economic, political, and logistical challenges of student loan forgiveness, check out this podcast I shared in last week’s assorted links post:

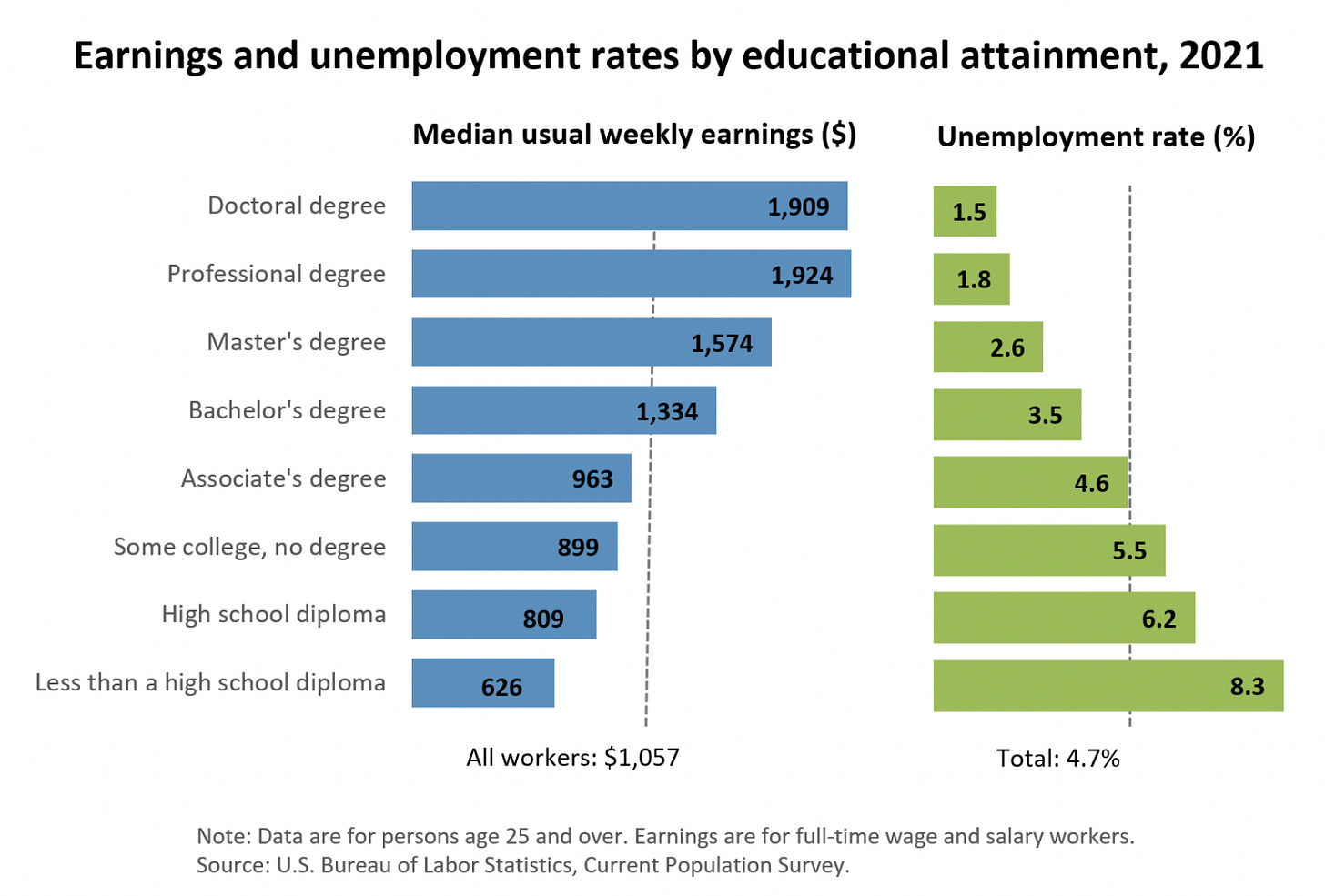

There are a number of benefits associated with obtaining additional education beyond a high school degree, including lower unemployment rates and higher earnings. In order to obtain those benefits, however, there are some serious upfront costs. The most obvious costs, tuition and fees, can be relatively small compared to the opportunity cost of spending additional time in school instead of working full-time. Recognizing opportunity costs can be challenging for a lot of people.

Economists look at these sorts of decisions (and others like moving to a new city or improving your health) as investments in human capital. Pay an upfront cost now and reap benefits later in life. One of the big concerns recently, however, has been the growing cost of these investments. Average tuition and fees, after controlling for inflation, are 19% higher over the past decade for 2-year institutions and 16% higher at 4-year institutions. The only institution that saw decreases in tuition costs were private, for-profit institutions.

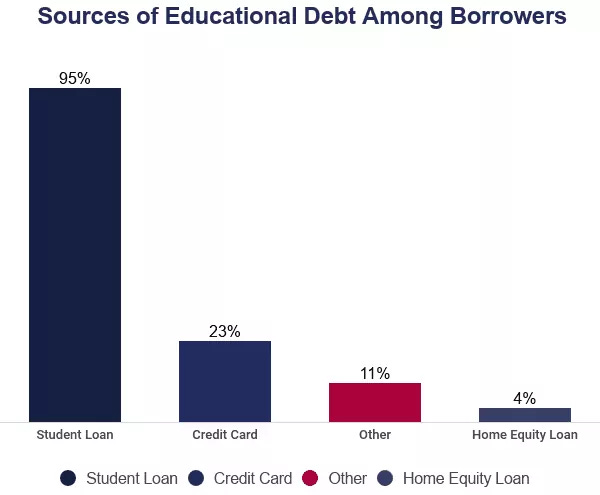

Funding these sorts of investments can be challenging, particularly for young borrowers who haven’t had time to establish a credit score that would make denote them as trustworthy borrowers. If a fresh high school graduate wanted to purchase a new car, they would pay a relatively small amount upfront as a down payment and would likely then borrow the rest from a bank. The interest rate on that loan would be based on their credit scores. A high school graduate could attempt to take a loan for their college degree, but it would be much more challenging.

Financial institutions are generally biased in favor of physical capital rather than human capital. Both have upfront costs that provide benefits, but physical capital can be repossessed if the loans are not prepared. This makes the investment safer, from the bank’s perspective. If a young borrower spends the money on tuition, they receive an education (and all the benefits of that education), but the bank is unable to repossess the degree if the student misses payments or chooses to stop making payments. If our young borrower isn’t able to keep up with their car payments, the bank could repossess the car that was used as collateral and regain some (or all) of their loan.

This capital market imperfection is often used as a justification for government involvement in the financing of higher education. There are other social benefits associated with a more educated population, including increased participation in the political process, scientific discoveries, entrepreneurship, and enhanced productivity. Each of these also justifies some level of government intervention in education. In 2019, state and local governments spent $311 billion on higher education, which was about 9% of state and local direct general spending. The student loan program, however, has grown into a much bigger issue since it was privatized back in the 1990s. Adam Conover had a nice summary (albeit a little explicit) of the federal student loan problems on his show Adam Ruins Everything:

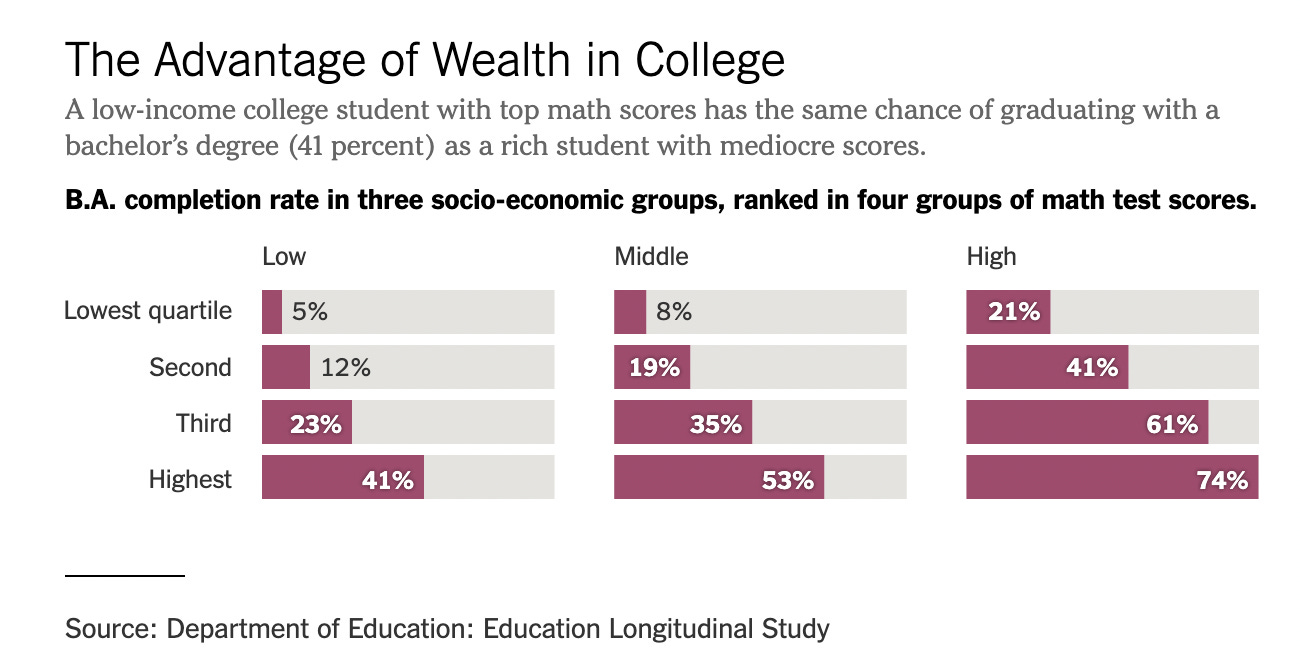

Government-backed loans for higher education serve an important purpose in the investment decision for many young people. This is especially true for students who don’t have the same level of access to private financing options as other students. Private loans may require some sort of collateral, but students from low-income families may not be able to secure that collateral. The graduation gap between low-income and high-income students is worse than the enrollment gap, but the increasing cost of a college degree only makes things worse:

Forgiving student loans, even if it’s just a small fraction of someone’s overall student loan debt, won’t eliminate the underlying problems with the structure of this particular type of debt financing. Forgiveness will bring relief to some borrowers and will likely be an unnecessary break for others. The bigger issue that needs to be addressed is how this process can be restructured so that future borrowers are able to successfully repay loans they take out for their investment.

Federal student loans have an interest rate ranging from 3.73% to 6.28%, while the average private student loan rate can range from 2.99% to 12.99% [BankRate]

Student loan debt in the United States totals $1.747 trillion [Education Data Initiative]

College graduates from the class of 2020 who took out student loans borrowed $29,927 on average [US News and World Report]

About 42% of students at four-year public universities finished their bachelor’s degree without any debt [Association of Public & Land-Grant Universities]

About 92% of all student debt are federal student loans; the remaining amount is private student loans [Forbes]

There were nearly 250,000 fewer students enrolled in college at the end of 2019 than in the previous year [National Student Clearinghouse]