What’s Going On With the Jobs Numbers?

Revisions aren’t a sign of failure.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

On Friday morning, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the U.S. economy added 73,000 jobs in July. By Friday afternoon, the head of the Bureau had lost hers.

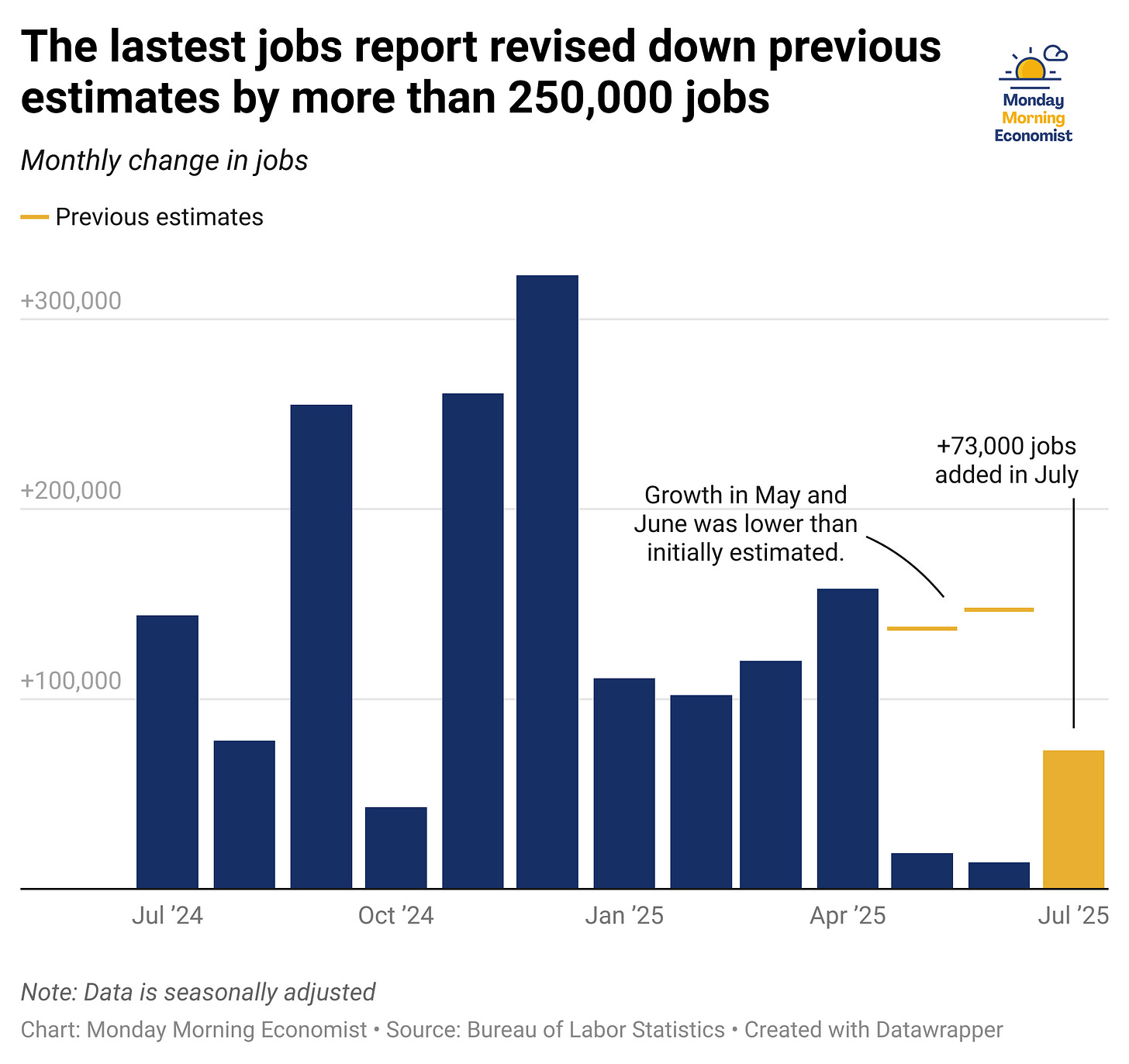

The reason? President Trump accused Dr. Erika McEntarfer, the commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, of manipulating the data for political purposes. The last report showed a sharp slowdown in hiring and a big downward revision of job growth that had been estimated in the previous two months. All in, about 258,000 jobs that had been previously “added” were removed.

To be clear, this isn’t the first time a politician has been unhappy with economic data. But firing the head of the agency that produces that data? That’s new.

The BLS has been entrusted as the primary data producer in the federal government. It’s a technical, statistical operation run almost entirely by career civil servants. The commissioner is the only political appointee in the entire bureau.

The decision to remove the commissioner breaks with the long-standing norm that economic statistics should be free from political interference. But it also raises broader questions about how labor market data is collected, why it gets revised, and what those revisions really mean.

So, What Is This Report Everyone’s Arguing About?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics does a lot. It tracks inflation, wages, productivity, and prices for everything from eggs to eyeglasses. But the spotlight right now is on one report in particular: the Employment Situation Report. It’s the country’s monthly check-up on how the job market is doing.

This report delivers two headline numbers at the start of each month:

The unemployment rate comes from a survey of about 60,000 households. It tells us what share of people are out of work and actively looking.

Total nonfarm employment is based on a separate survey of employers and tells us how many jobs exist in the economy (minus a few categories like farm work, military jobs, and some gig work).

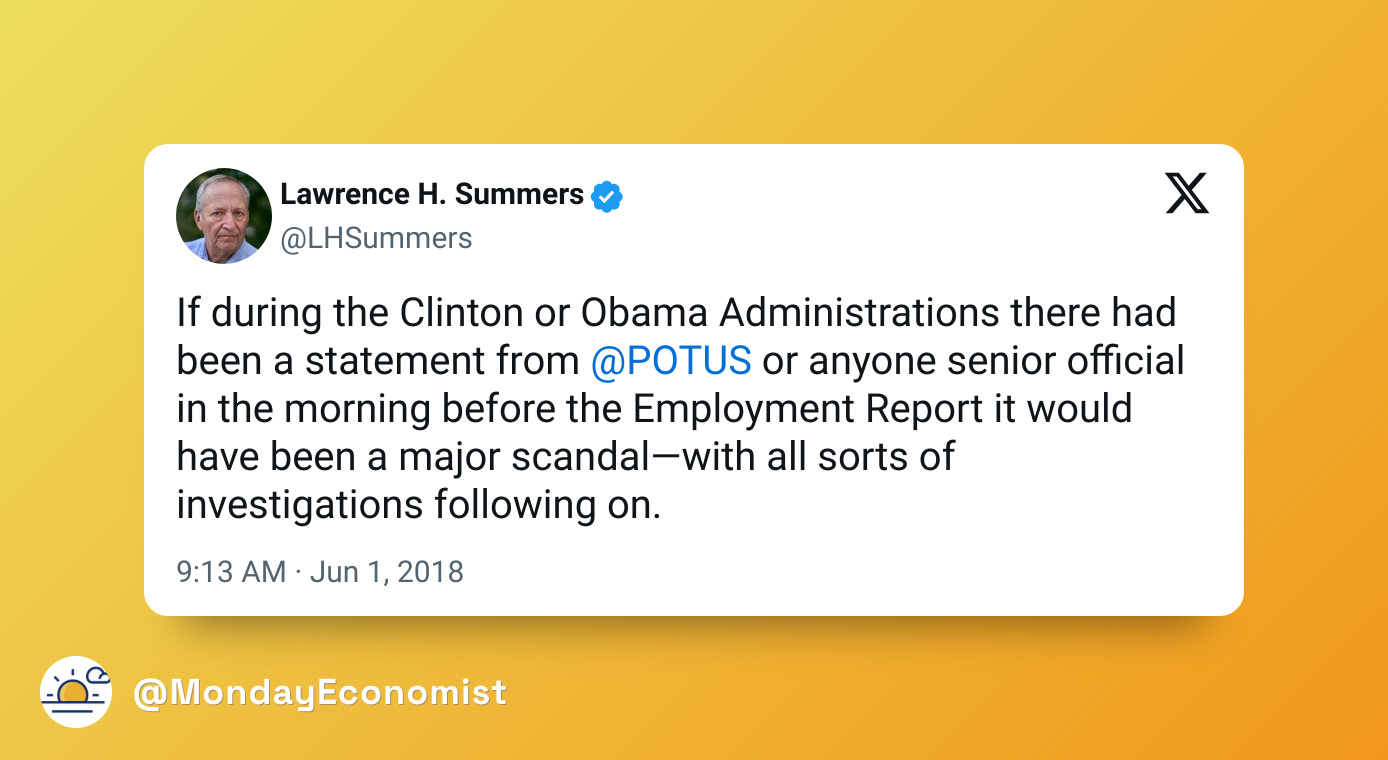

The jobs report gets a lot of attention each month for good reason. It can move markets, shape policy, and quickly become political ammunition. In 2018, then-President Trump hinted on social media that a strong report was coming before it was officially released. Investors got the message: stock futures and bond yields jumped almost immediately. Just a tweet about the release was enough to move the market, which tells you how powerful this data really is.

But getting this estimate right the first time can be challenging. The headline number covers data that was collected just a few weeks earlier. That makes it incredibly useful for real-time decision-making. But it also means the first report is considered preliminary. The first number is rarely the final number.

And that’s where last week’s controversy begins.

Why Are the Numbers Revised?

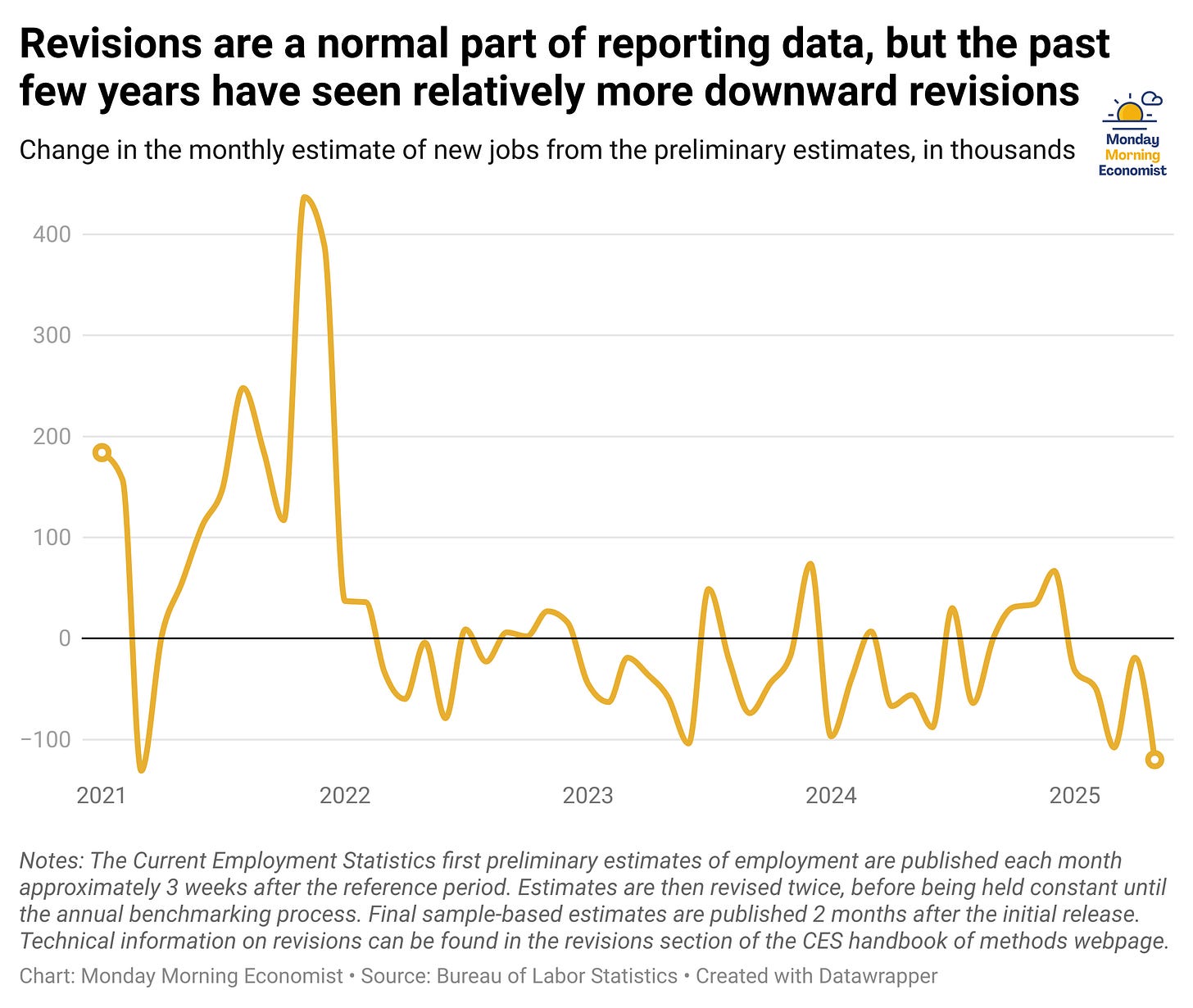

The job numbers you see in the headlines each month almost always get revised. Every month. It’s a normal part of how the BLS operates. This isn’t a new.

The employment data is based on a huge survey called the Current Employment Statistics (CES) survey. It goes out to about 122,000 businesses and government offices, covering more than 600,000 worksites. It takes a massive effort. But not everyone gets their data in on time. Some businesses respond late. Others don’t respond at all.

Sometimes, unexpected events make the first estimate even trickier. A hurricane disrupts surveys from an affected region, or a global pandemic throws off everything. Regardless of what’s happening, policymakers and markets don’t want to wait six months for perfect numbers.

So, the BLS has to make an educated guess using statistical models based on historical trends to fill in the blanks. They publish a preliminary estimate at 8:30 AM on the first Friday of every month. Over the next month or two, more responses come in. The models get adjusted, and the original estimate gets revised in the next jobs report.

It’s not a mistake to revise. It’s just what happens when you replace early estimates with more complete data.

Why It’s So Hard to Get the Number Exactly Right

If you’ve ever taken a statistics class, you’ve probably heard about samples and populations. It’s a foundational idea in statistics: if you can’t ask everyone, you ask a slice and use that to estimate the whole.

The BLS tries to do just that. Every month, it sends out surveys to about 122,000 businesses to estimate what’s going on across an economy with more than 12 million establishments and 156 million workers.

It’s a lot like trying to figure out how the crowd feels at a baseball game by asking a few dozen fans. If they’re loud and in sync, you’ll probably get a good read. But if they’re on the quiet side or sitting in the wrong section, you could miss the bigger picture.

This is where statisticians like to bring up the Law of Large Numbers. It’s the idea that as your sample gets bigger, your estimate tends to get closer to the truth. That’s why early job numbers are revised. As more responses come in, the models get better and the estimate gets more accurate.

But here’s the problem: that’s getting harder to do.

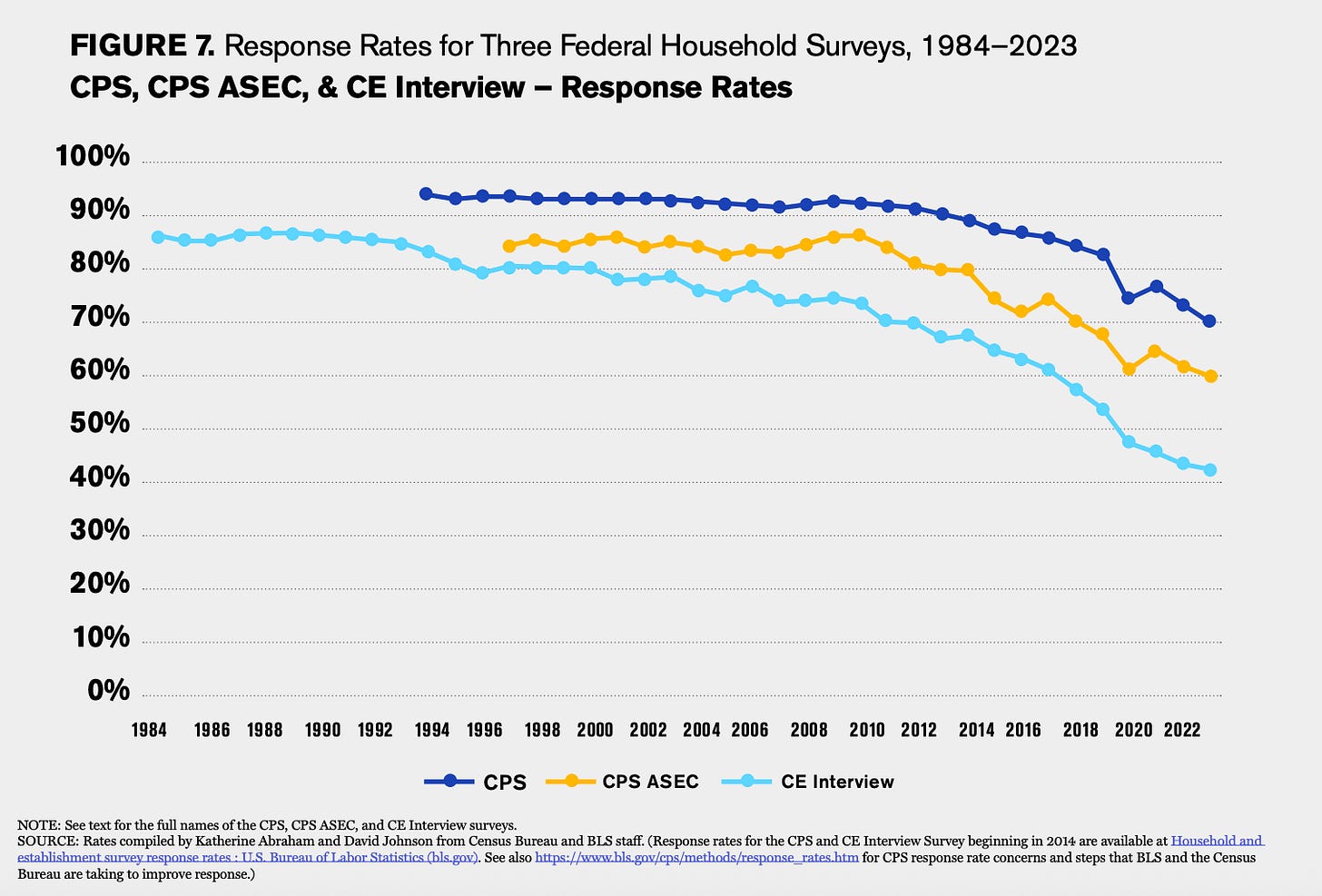

According to a recent report from the American Statistical Association, the entire federal statistical system is under strain. Response rates are falling. Budgets are tight. And staffing at key agencies like the BLS is shrinking, thanks to layoffs, hiring freezes, and early retirements. That means fewer people to chase down late surveys, check the models, or explain what changed and why.

So yes, the job numbers are based on a massive sample. And yes, they usually get better with time. But building and maintaining a system that can do all of this accurately and independently takes resources, trust, and time.

Oh, and firing the umpire doesn’t change the score of the game, and firing the BLS commissioner doesn’t change the data that was collected.

Final Thoughts

Revisions aren’t unique to the BLS. The Bureau of Economic Analysis tracks GDP and income in the United States, and revises its numbers, too. Instead of seeing revisions as a sign of mistakes, it should be interpreted as a sign that economists care enough to get it right, even if it takes a few months.

It’s also worth noting that the U.S. is unusual in just how much economic data it produces and how fast it does so. Most of it is collected by career civil servants, made public, and open to scrutiny. In a country as big and complex as this one, that kind of transparency is valuable to all of us.

So yes, the job numbers will change. The job numbers we get each month are estimates. They aren’t perfect, and they aren’t final. But they’re the best picture we have, updated as we learn more. And that’s the kind of system we should want.

Thanks for reading the Monday Morning Economist. If you found this post helpful, consider forwarding it to a data skeptic or anyone who’s been asking about revisions. You might just help them see why even messy numbers can still tell a meaningful story.

The Bureau of Labor was established in the Department of Interior in 1884 [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

The BLS’s first report on employment was based on data from ~200 employers in the clothing and textiles industry in late 1915 and published in early 1916 [Marketplace]

Erika McEntarfer was confirmed by the Senate 86-8 in January 2024 for a term of four years [U.S. Congress]

By the end of the day, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by 542 points, the Nasdaq Composite dropped 2.3 percent, and the S&P 500 decreased 1.6 percent of its value [The Hill]

Absurd to fire honest & professional statisticians because you do not like the numbers! 👎

When I teach my ECON 101 students about GDP, I express it is a measurement, but it is flawed. The employment numbers are the same. To assume one entity can just track all the employment numbers without issues is simply unrealistic. It may not be a perfect measure, but it is something. If anyone has a better measure, please let me know. Thanks for sharing.