$240,000 in-office vs. $120,000 remote

How much income does a worker require to give up job amenities like flexibility, autonomy, and location choice?

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

If you’ve spent any time on social media over the past few weeks, you’ve probably seen this debate scroll past your screen. A hypothetical job offer has split the internet in half: $240,000 to work in an office five days a week versus $120,000 for a fully remote role.

The question first went viral after an influencer posed it to her audience. Millions of views later, the comments section looked less like career advice and more like group therapy. Some people argued the choice was obvious. Others said no amount of money could convince them to return to an office.

At first glance, this may just look like a simple debate about flexibility, burnout, and work-life balance. But underneath the back-and-forth is something much more interesting. This is a clean, real-world example of how economists think about wages, job amenities, and trade-offs.

Let’s put an economics spin on it.

Why wages change when job perks change

The reason this question traveled so far online is fairly simple. It forces people to put a price on things that rarely come with a price tag.

Commutes.

Flexibility.

Mental health.

Control over where you live.

Most jobs require people to accept these characteristics as a bundle in exchange for a paycheck. The costs and benefits are real, but they’re not usually itemized on a pay stub. This hypothetical pulls those hidden pieces out into the open and asks people to do something mildly uncomfortable: value them explicitly.

That discomfort is exactly where the economics gets interesting.

Introductory economics courses often describe wages as payments for productivity. That’s mostly true, but it’s far from a complete story. Wages are also shaped by who is willing to do the job under the conditions offered.

And this is where compensating wage differentials come in.

Economists think about job perks and job downsides as forces that shift the supply of workers willing to take a particular job. If a position comes with unpleasant or restrictive features, fewer workers are willing to supply their labor at any given wage. As a result, firms must raise pay to lure enough workers to the position. On the other hand, a job that comes with attractive perks also comes with more workers willing to apply. For these positions, firms can offer lower wages and still fill positions.

This theory has been around just as long as economics as a discipline has, and it shows up throughout the labor market. Dangerous jobs, night shifts, physically demanding work, or rigid schedules tend to pay more because fewer people are willing to do them. Jobs with flexibility, safety, or desirable working conditions attract more applicants and can often pay less.

It turns out remote work fits cleanly into this framework.

The office premium is a labor supply problem

Now let’s return to the social media hypothetical and think carefully about what the higher-paying job actually requires.

The in-office job comes with a daily commute, geographic restriction, less control over one’s schedule, greater monitoring, and fewer options for relocation or childcare flexibility. For many workers, those features reduce their willingness to supply labor at a given wage.

That reduced supply shows up as a higher salary. The extra $120,000 is the market’s response to fewer people wanting that particular bundle of job characteristics. If working in an office five days a week were widely preferred, firms wouldn’t need to offer such a large premium to staff those roles.

That doesn’t mean in-office work is “bad.” It means that, in today’s labor market, it narrows the pool of willing workers. Higher pay is how firms compensate for that.

When perks flip the story

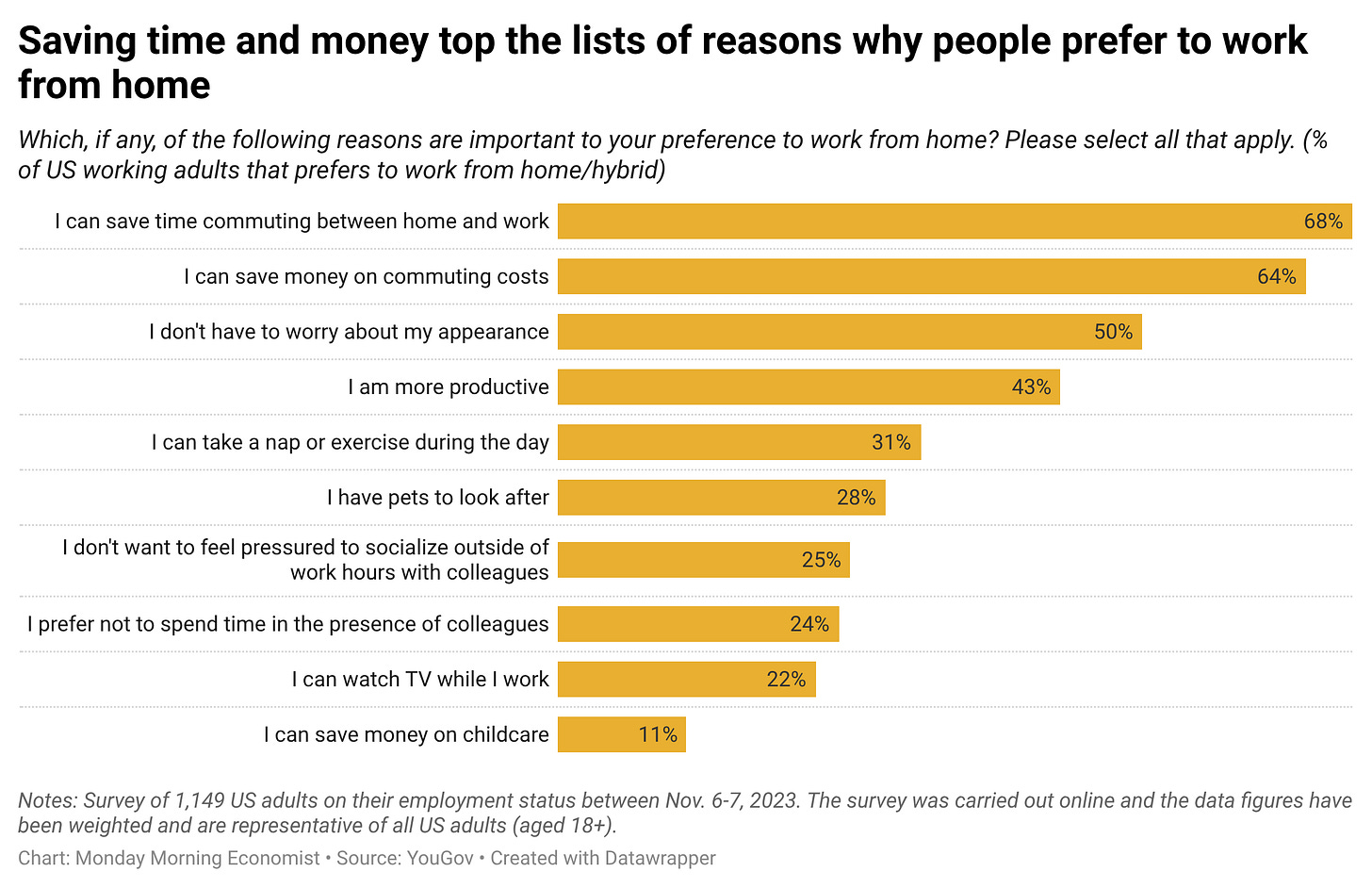

The same logic explains why some workers are perfectly happy taking the lower-paying remote job. Remote work expands the supply of workers willing to take that role. No commute, lower transportation costs, the ability to live in a cheaper city or closer to family, and greater schedule flexibility all make the job attractive to a larger group of people. When supply increases, wages don’t need to be as high to fill positions.

For some workers, the value of those nonpecuniary benefits is so high that even $240,000 wouldn’t be enough to give them up. That choice is just a reflection of their preferences. Afterall, workers are heterogeneous.

Two workers can look at the same pair of job offers and reach different conclusions because their constraints, responsibilities, and life stages differ. What feels like a disamenity to one person may be an amenity to another.

Final Thoughts

Perhaps one of the most revealing parts of the online debate came from parents, especially working mothers. Several offered some version of the same insight: “If I were single, I’d take the $240,000. As a parent, I’d take the $120,000.”

Economists don’t expect uniform preferences across workers. The same job attribute can be a perk for one person and a burden for another. That insight helps explain why firms struggled so much with return-to-office mandates over the past few years. Those policies change job amenities for everyone, even though workers value those amenities very differently.

It’s also easy to say online that you’d take the $120,000 remote job. It sounds principled. It sounds healthy. It sounds modern. But this is where economists distinguish stated preferences and revealed preferences.

When real offers are on the table, people rarely give up half their salary for flexibility alone. Research consistently finds that workers are willing to accept lower pay for remote work, but not on the order of 50%. The actual trade-off tends to be much smaller.

The real value of this viral question isn’t choosing a side. It’s recognizing that wages pay for more than labor. They also pay for time, comfort, flexibility, and peace of mind.

Have a friend who hates their commute and wishes they could work from home? Send this along and ask them how much they’d really be willing to give up for it.

Just over a third (36%) of workers say they would want to work fully remotely [YouGov]

Although fully remote workers report higher engagement, they are less likely to be thriving in their lives overall (36%) than hybrid workers (42%) and on-site remote-capable workers (42%) [Gallup]

About 20% of private salary and wage workers were still working from home for at least some of their hours as of April 2025, while just under 10% were working remotely every day [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

In a 2025 survey of nearly 1,400 U.S. tech workers, respondents said they would be willing to give up about 25% of their pay for an identical job offering partially or fully remote work instead of requiring full-time, in-person attendance [AEA Papers & Proceedings]

I think the thing to know is how creepage works in this. I know many WFH folks that long on early and stay later. While a great many in office people are have incentives to leave as soon as the clock strikes. Decision-making seems to evolve in this environment as well. There have been surveys in the past that show when cuts are needed remote workers are at the top and they are in the bottom for promotion.

Thank you, Jadrian-san, for such an insightful piece. It provides a great perspective on how we value our time and autonomy.

While a $120,000 pay gap is significant enough to sway many people toward the office, I believe forward-thinking companies should lean into the massive value of non-pecuniary benefits as a competitive edge.

Modern workers aren't just chasing a paycheck; they’re looking for a “total lifestyle package.” It’s about the overall life satisfaction they gain by being part of an organization. By framing remote work and flexibility as a strategic asset—rather than a reluctant compromise—companies can create highly adaptable organizations that naturally attract talent without being held back by labor shortages.

Designing value that goes beyond wages is no longer just a "perk"; it’s the future of organizational competitiveness.