Puerto Rico by the Numbers

After the Super Bowl spotlight fades, the data tell a deeper story about the island’s economy.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Last week’s Super Bowl halftime show was impressive. Viewership numbers placed it near the top of the record book, and social media buzzed for days. In the middle of America’s biggest sporting event, millions of viewers were immersed in the sights and sounds of Puerto Rico.

Bad Bunny’s performance was more than entertainment. It was a carefully constructed portrait of everyday life on the island: sugarcane stalks on stage, a piragua stand selling shaved ice, barber shops and nail salons, domino tables, boxers sparring under bright lights.

The intent was a cultural celebration. But it also raised an economic question: what does Puerto Rico’s economy actually look like?

Only around two-thirds of Americans can confidently say that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. Even fewer could likely describe how its labor market performs or what industries drive production on the island. The halftime show placed Puerto Rico in the spotlight. This week, we’ll examine the numbers behind it.

A Unique Economic Relationship

Puerto Rico’s economic story is inseparable from its relationship with the United States. Since 1898, the island has been deeply integrated into the U.S. economy, though never fully incorporated as a state. It adopted its own constitution in 1952, yet remains subject to federal law. Residents are U.S. citizens by birth, and goods move freely between Puerto Rico and the mainland.

But integration does not mean equivalence.

Puerto Rico has no voting representation in Congress. Residents generally do not pay federal income taxes on income earned on the island, though they contribute to payroll taxes such as Social Security and Medicare. The island does not control monetary policy or its own currency. When the Federal Reserve adjusts interest rates, Puerto Rico adjusts with it.

For decades, federal tax provisions encouraged pharmaceutical and manufacturing firms to locate production on the island. Those policies helped build a strong industrial base, but investment declined when the incentives were phased out in the mid-2000s. The island entered a prolonged recession that contributed to rising public debt and accelerated out-migration.

Puerto Rico operates inside the U.S. economic system, but without the full policy tools of a state. That distinction shows up clearly in the data.

What Does Puerto Rico Produce?

Based on the halftime show, you might assume Puerto Rico’s economy revolves around tourism and small neighborhood businesses. Those sectors matter, but the data tell a more industrial story.

Manufacturing accounts for roughly 44% of Puerto Rico’s total output. In the United States as a whole, manufacturing contributes closer to 10% of GDP. By production alone, Puerto Rico looks far more industrial than most states.

Pharmaceuticals and medical devices dominate exports, and the island is still a critical hub in the U.S. drug supply chain. But production and employment tell slightly different stories.

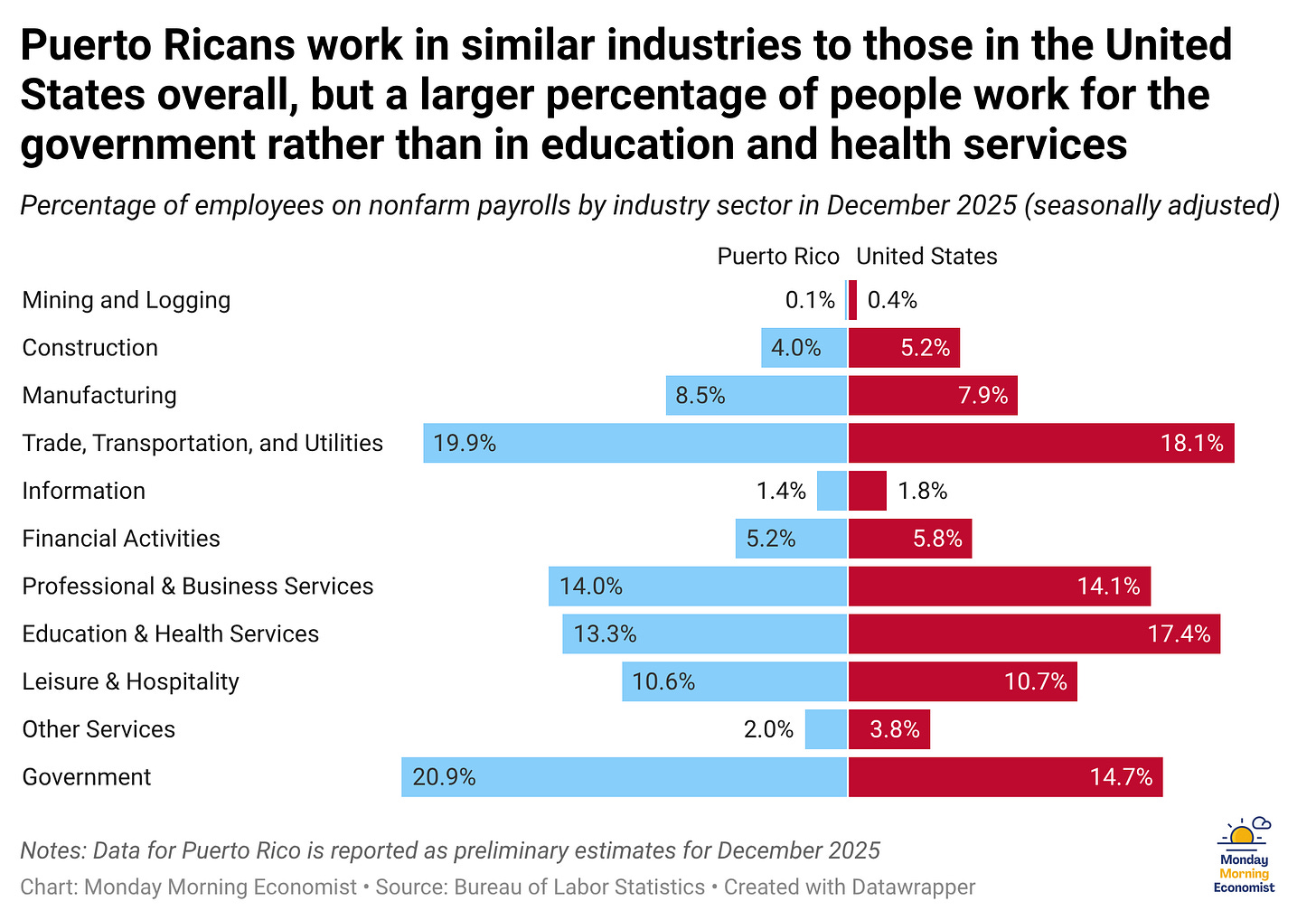

When we look at employment, Puerto Rico closely resembles the mainland. Most workers are employed in services like retail, healthcare, education, and government, just as they are across the United States. Manufacturing employs a relatively small share of workers.

So how can manufacturing account for nearly half of output but only a modest share of jobs?

The answer lies in capital intensity. Pharmaceutical production relies on advanced facilities, specialized equipment, and intellectual property. A relatively small workforce can generate substantial output. Output per worker is high, but those gains do not necessarily spread evenly across the broader labor market.

Therefore, services dominate employment. Government employment, in particular, represents a larger share of total jobs in Puerto Rico than in the United States overall. That reflects the structure of the local economy and the underdevelopment of the private sector.

Once centered on sugarcane, agriculture now plays only a minor role in both output and employment. The sugarcane displayed during the halftime show symbolized history more than present-day production. The Puerto Rican economy resembles a specialized manufacturing hub layered on top of a service-oriented labor market. That distinction matters when we examine income and growth.

The Numbers: Puerto Rico vs. the U.S.

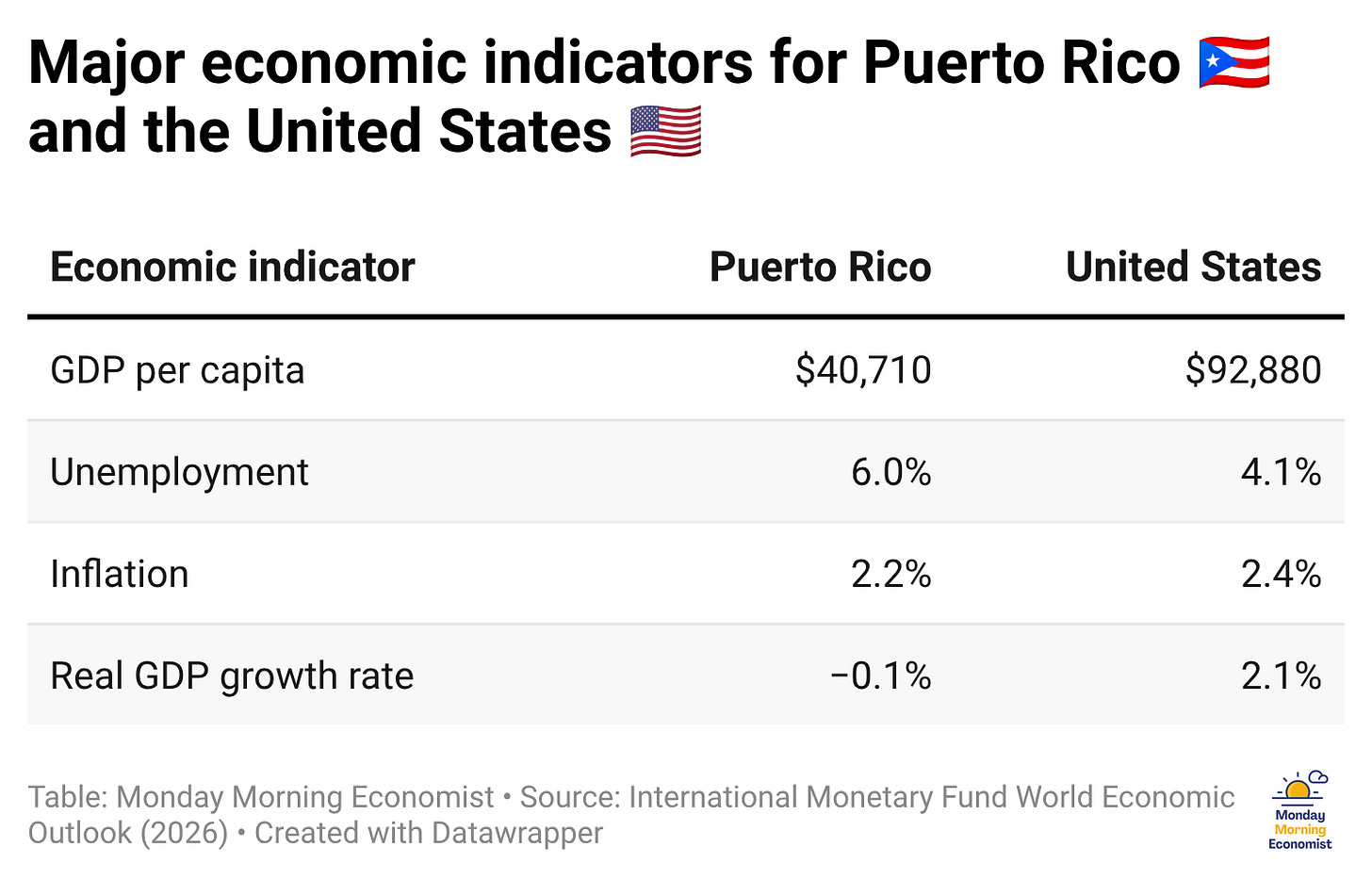

Employment shares may look similar, but the broader economic outcomes do not. To compare Puerto Rico and the United States, we turn to four popular indicators: income per person, unemployment, inflation, and economic growth.

Because the U.S. government does not publish all macroeconomic measures for Puerto Rico in the same way it does for the states, these figures rely on data compiled by the International Monetary Fund.

Income per Person

Puerto Rico’s GDP per capita is roughly half that of the United States overall. If ranked alongside the states, the island would fall below Mississippi, currently the lowest-income state.

Despite its large manufacturing sector, much of that output is capital-intensive and tied to multinational firms. The value added does not translate into broad-based income gains across the population. Lower income levels create persistent pressure, particularly for younger and more educated workers.

Unemployment

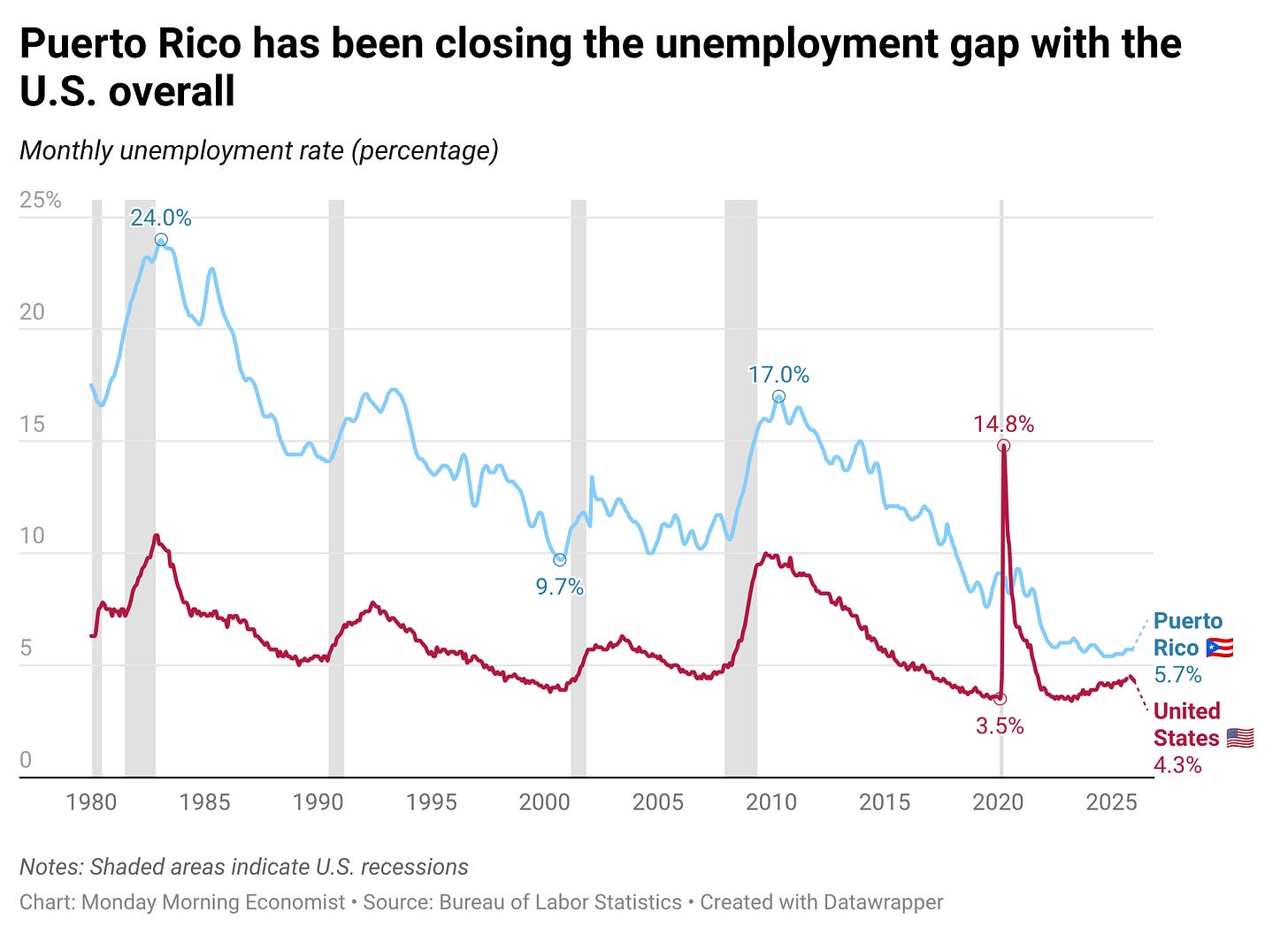

The unemployment rate has improved substantially from the double-digit levels seen a decade ago, but it remains several percentage points higher than the U.S. average.

Labor force participation is also significantly lower. A smaller share of working-age adults is either employed or actively seeking work. That pattern reflects long-term economic adjustment and demographic shifts.

Inflation

Inflation in Puerto Rico generally moves alongside U.S. inflation. The island uses the dollar, imports most consumer goods, and shares the same monetary policy.

Geography, however, introduces structural cost pressures. Nearly all goods arrive by boat or plane. Shipping regulations under the Jones Act and higher energy costs can elevate baseline expenses. When inflation rises on the mainland, Puerto Rico feels it. When transportation or energy costs increase, those effects can be magnified.

Economic Growth

Growth provides the clearest divergence. Recent data show Puerto Rico’s real GDP growth hovering around zero, while the United States has grown at roughly 2% annually.

Growth determines whether income gaps narrow or widen. An economy that grows more slowly gradually falls behind. Puerto Rico’s slower growth reflects population decline, industrial concentration, and the lingering effects of prolonged recession.

Final Thoughts

The data points to a consistent direction. Puerto Rico shares the currency, monetary policy, and much of the employment structure of the United States. Yet incomes are lower, unemployment is higher, and growth has lagged.

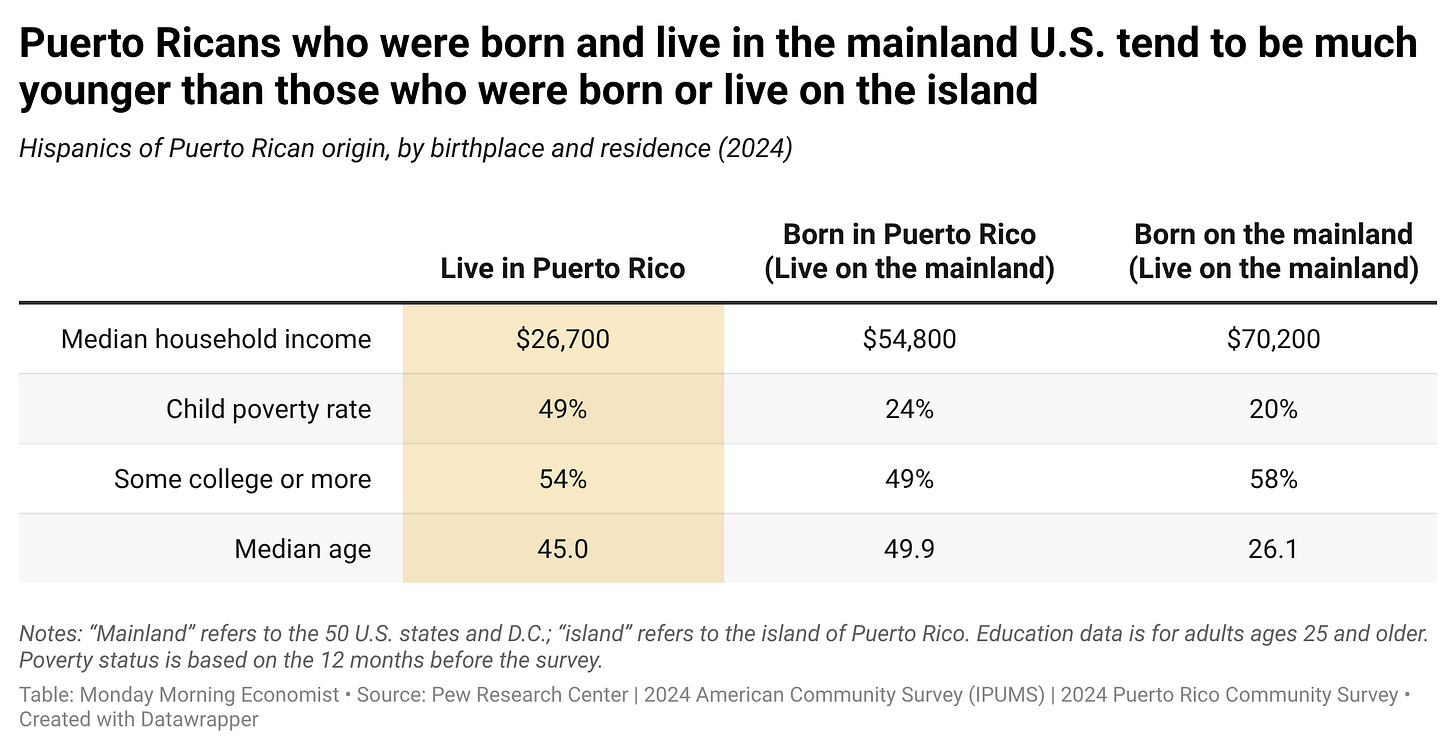

Perhaps the most important consequence of those differences is migration.

Over the past two decades, hundreds of thousands of younger, working-age Puerto Ricans have moved to the mainland United States. Migration is often described as cultural, but it is also economic. When income gaps persist and growth stalls, labor moves toward opportunity.

Higher earnings and stronger labor market outcomes on the mainland create a steady pull, while slower growth at home reinforces the push. Migration can ease short-term labor market pressure, but over time, it shrinks the working-age population and narrows the tax base. An economy that steadily loses younger workers faces structural issues that compound over time.

The halftime show celebrated Puerto Rican culture in vivid detail, but behind that cultural celebration is a complex macroeconomic reality.

Enjoyed this analysis? Economics is better when it’s shared with friends.

With a population of about 3.2 million, Puerto Rico is larger than 18 states and the District of Columbia [Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy]

About 125 million people in the US watched Super Bowl LX, but Bad Bunny’s halftime performance registered an even larger audience: 128.2 million viewers [CNN]

A 1917 act of Congress established that people born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens [Immigration History]

About 47% of Puerto Ricans lack confidence in their ability to absorb a $2,000 economic shock [CNBC]

If the residents of Puerto Rico voted in favor of it, 52% of U.S. adults would support their vote [YouGov]

Puerto Rico’s population shrank by 13.73% between 2000 and 2020, from 3.8 million to about 3.2 million [Financial Oversight & Management Board for Puerto Rico]

Cuppla things: 1. Japan was rebuilt under US tutelage at about the same time as PR -- obviously it has done better. One reason is that PR has private industries that are not home-grown, but are owned by mainland companies -- this means there is no scientific or research establishment for the pharma industry, no University support, no one doing large-scale studies for the FDA -- all the apparatus of pharma, unlike in Japan -- only workers. Almost all ownership is offshore, meaning profits go to US households -- dependency at its finest. 2. Almost all economic growth in the US for the last ten years has been in tech -- more recently, only in AI. None of that exists in PR. 3. PR has a major agricultural research station -- the USDA-TRS Tropican Agricultural Research Station, associated with the University of PR. Agricultural research, however, has been a backwater in economic growth for a century or more -- the most likely avenue to profit growth in agriculture is production of drugs using genetic modification, which they do not do.

It’s interesting to see how these macro indicators show both similarities and differences across economies. Great read!