Groceries Aren't Cheap for Russians

Tucker Carlson's grocery bill in Russia tells us more than just the price of bread and milk in Moscow.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 3,800 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

Tucker Carlson, the former Fox News firebrand, recently found himself wandering the aisles of a Russian supermarket. He’s supposed to be in Russia for journalistic reasons, but he’s found his way to a local supermarket for an economic experiment. His mission was simple: to shine a light on the cost of living in Russia, presenting it as a bargain compared to back home in the United States. The ultimate goal? To point a finger at U.S. political leaders, accusing them of letting the American standard of living slip.

But Carlson failed to recognize a simple economic concept—Purchasing Power Parity, or PPP for short. It’s a concept that’s used to scale and compare what a dollar really means from one country to the next, adjusting for the cost of living. Instead of a clear-cut case of Russian affordability, Carlson provided us all with a learning opportunity.

Shopping cart in hand, Carlson navigates the fluorescent-lit aisles of a Russian supermarket. He and his crew are trying to fill their cart with a week’s worth of groceries. At the checkout, they reckon their cart would cost about $400 back in the United States. Yet, the total comes to just 9,481 Russian Rubles—a sum that comes out to slightly over $100 after adjusting for the current exchange rate.

Carlson is stunned, his reaction a mix of astonishment and indignation at the perceived bargain. He goes as far as to say he’s been “radicalized” against U.S. leaders because of his findings. But we must call out his mistake. This comparison draws from his experience earning American dollars and overlooks a critical detail. What feels like a steal to an American is, for many Russians, a hefty expenditure. Russian groceries aren’t cheap if you live and earn income in Russia.

The Flaw in Carlson’s Comparison

Let’s assume Carlson’s outrage stems from a genuine concern for the economic strain felt by many Americans. By the end of 2023, grocery prices were up 5% from the same time last year. That slight increase is enough to take a big bite into the budgets of American families. A survey by the U.S. Census in October 2023 paints a stark picture: about 12.5% of adults reported not having enough to eat in the past week alone.

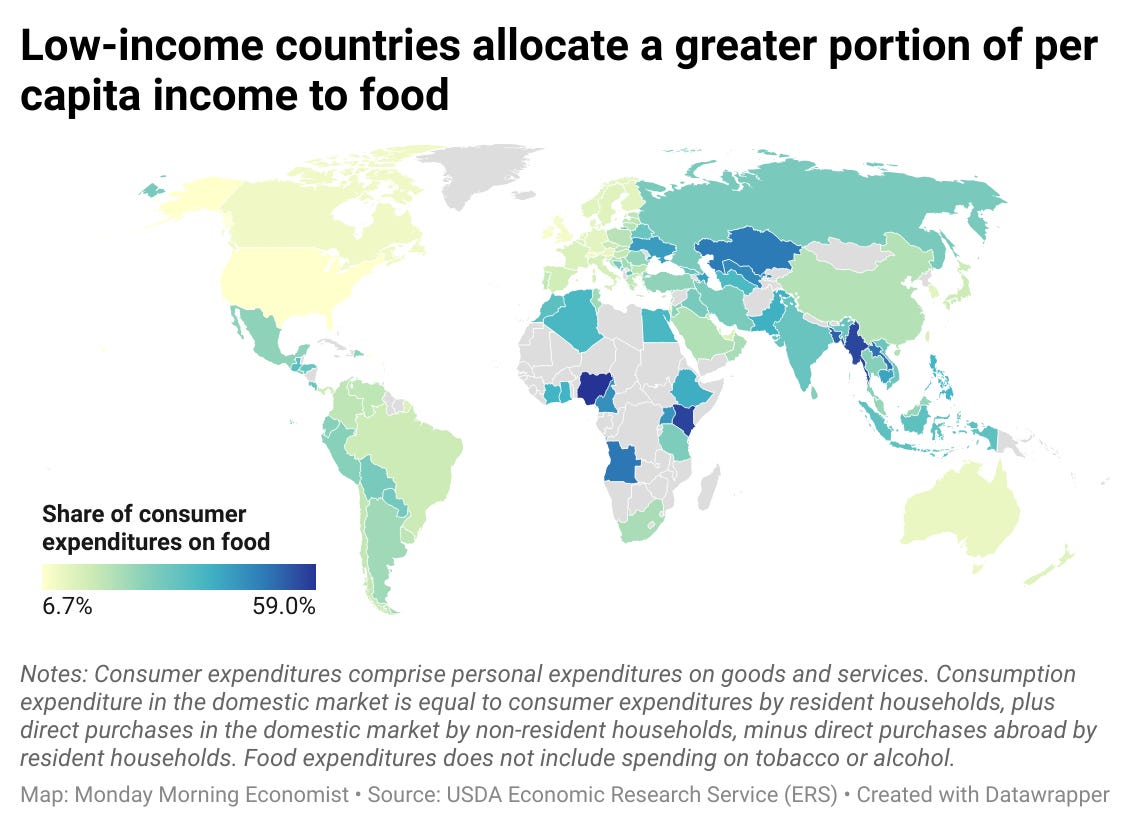

But Carlson glosses over the stark income disparity separating the United States and Russia. When those groceries are tallied at the Russian checkout, they consume more than half of the average Russian’s weekly earnings. This isn’t unique to this particular store. The majority of Russians spend about half of their monthly income on food. To put that into perspective, consider this: in the United States, groceries (food at home) account for about 6.7% of household expenditures.

Generally, as countries become wealthier, they might spend more on food but spend a smaller share of their income on food; it’s a concept known as Engel’s Law. Spending more on food in absolute terms is often a sign that people are eating more diverse diets. But this goes beyond food at a grocery store.

People from wealthy countries make the same mistake Carlson made all the time but in more innocent ways. Have you gone on a vacation to a warm, tropic island and thought about how nice it was to live somewhere because everything seemed so cheap? What seems cheap by American and British standards is a much different story for the people living on those islands.

We often don’t point out the mistakes of our traveling companions, but Carlson’s oversight has sparked criticism, and for good reason. Carlson’s antics are a stark reminder of the complexities of comparing lives across borders and caution against simplistic narratives that might inadvertently glamorize life under authoritarian regimes.

The Essence of Purchasing Power Parity

So, how can we understand the value of a dollar, a ruble, or any currency, for that matter, when we step across international borders? We can rely on Purchasing Power Parity, or PPP, to help us with the heavy lifting. PPP enables us to view and understand the actual buying power of money in different corners of the globe. The concept lets us strip away the distortions caused by fluctuating exchange rates and the variances in price levels from one country to another.

In its most basic form, the PPP shows us how much a specific good or service costs in one country compared to another, all boiled down to a ratio. But how do we arrive at this comparison? Economists select a basket of precisely defined goods and services that are common across countries. They tally up the cost across countries and tweak the exchange rate until these hypothetical basket costs are the same in both places. This generates the PPP exchange rate, which tells us more about real wealth and living standards than any currency exchange site ever.

Real Data Analysis: Russia's Case

Recent data suggests that the average monthly paycheck in Russia comes in around 73,383 Rubles. In dollar terms? That’s about $800, given the current dance of the exchange rates. A grocery bill totaling about 9,400 Rubles would be a significant slice of the average Russian’s monthly earnings. But what can PPP tell us about the cost of living in Russia?

Imagine we’re comparing the same basket of groceries in the U.S. to the one Carlson bought in Russia. If his basket really would have rung up to $400 stateside, we can see our first issue when comparing costs and currencies. By dividing the Ruble cost by the dollar cost (that's 9,400/400), we find a PPP exchange rate of 23.5 Rubles per dollar.

With the current market exchange rate hovering around 92 Rubles to 1 US dollar, a PPP exchange rate of 23.5 should raise some eyebrows. But what does that difference tell us? It’s whispering (or, perhaps, shouting) that the cost of living differs significantly more than what a simple currency conversion would suggest. If one US dollar buys you a certain basket of goods in the States, the equivalent of 23.5 Rubles (not 92) should fetch the same basket in Russia.

This disparity between the market exchange rate and the PPP rate highlights the differences in how far a dollar stretches in the US versus the Ruble in Russia. While it’s not a perfect measure it tells us about affordability and the real, day-to-day lives of ordinary people. It helps businesses and investors make informed decisions by offering a clearer picture of economic conditions and allows policymakers to better assess the competitiveness of economies and the effectiveness of their economic policies.

Tucker Carlson’s grocery store experiment in Russia, intended to critique U.S. economic policies, inadvertently highlights the importance of understanding PPP. While the nominal cost of living in another country might seem lower when directly converting currencies, this doesn’t necessarily mean that people in that country enjoy a higher standard of living. When accounting for PPP, we often find that apparent price disparities reflect deeper economic challenges, such as lower wages and higher relative costs of essential goods and services.

Russia’s annual inflation came in at 7.4% in January 2024 [The Moscow Times]

GDP per capita is approximately $83,060 in the United States and $13,320 in Russia [International Monetary Fund]

16% of Russians spend almost all their earnings on food [TASS]

The University of Pennsylvania and the United Nations joined forces in 1968 to establish the International Comparison Program to produce purchasing power parities (PPPs) and comparable price level indexes (PLIs) for participating economies [World Bank]

Liechtenstein has the highest real GDP per capita at $139,100 [CIA World Factbook]

In the article, it is mentioned that 12.5% of adults responded they did not have enough to eat in the past week alone. A few sentences later, 6.7% of household income is spent on groceries. I'm having trouble wrapping my head around these two percentages as they don't appear to be congruent.

The concept of currency exchange rates has always mystified me a bit.

Maybe you explained it in here and I didn't comprehend. But why is there such a large disconnect between the exchange rate, and the purchasing power calculations?

Or to ask more specifically, why would anybody give 92 rubles for one dollar, if that dollar can only buy them about 25% as many groceries as the 92 rubles?