Panda-monium Coming to US Zoos 🐼

China's recent decisions combine soft power, diplomacy, and... pandas. These beloved black-and-white bears are at the center of a quiet but significant shift in international relations.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of over 2,500 subscribers every week! You can support my newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid subscriber:

Dozens of beloved black-and-white bears are at the center of a quiet but significant shift in international relations. China, the nation that once used giant pandas to strengthen diplomatic ties with other countries, is now taking these pandas back from zoos around the world. It's a move that's left experts scratching their heads and has intriguing implications for international trade and diplomacy.

Three pandas housed at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., are scheduled to return to China as their loan agreement expires. Zoo Atlanta faces a similar prospect, with four pandas set to leave if a new deal is not reached. Britain and Australia are also bidding farewell to their resident pandas. If these agreements are not extended, the United States may find itself without giant pandas for the first time since 1972.

Beyond the Bamboo Forest

Giant pandas are more than just cute and cuddly creatures. For decades, they've been a symbol of friendship and goodwill, a source of what's known as soft power. Soft power is a nation's ability to influence others through non-coercive means, like culture and attraction. In the case of China, pandas are the epitome of their soft power. They have served as cute ambassadors that opened doors to discussions, economic partnerships, and goodwill gestures with other nations. These bears have an undeniable charm that transcends borders and languages.

Outside of a zoo setting, soft power can manifest in various forms, such as cultural exports like music, film, and cuisine, or through influential institutions like prestigious universities or organizations. For instance, the appeal of American pop culture, from Hollywood movies to the music industry, has long been a source of soft power for the United States, promoting its values, culture, and way of life worldwide.

Panda diplomacy isn't new; it has ancient roots dating back to the Tang Dynasty. Back then, emperors would gift pandas to neighboring nations as a symbol of peace and friendship. But it truly gained global prominence in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Initially, pandas were outright gifted to other countries as a sign of trust and friendship. But in 1984, China changed its approach. Instead of giving them away, they started leasing pandas, often with fees and terms and conditions attached. This shift marked a subtle yet significant change from pure goodwill to a more transactional form of diplomacy.

The U.S.-China Panda Connection

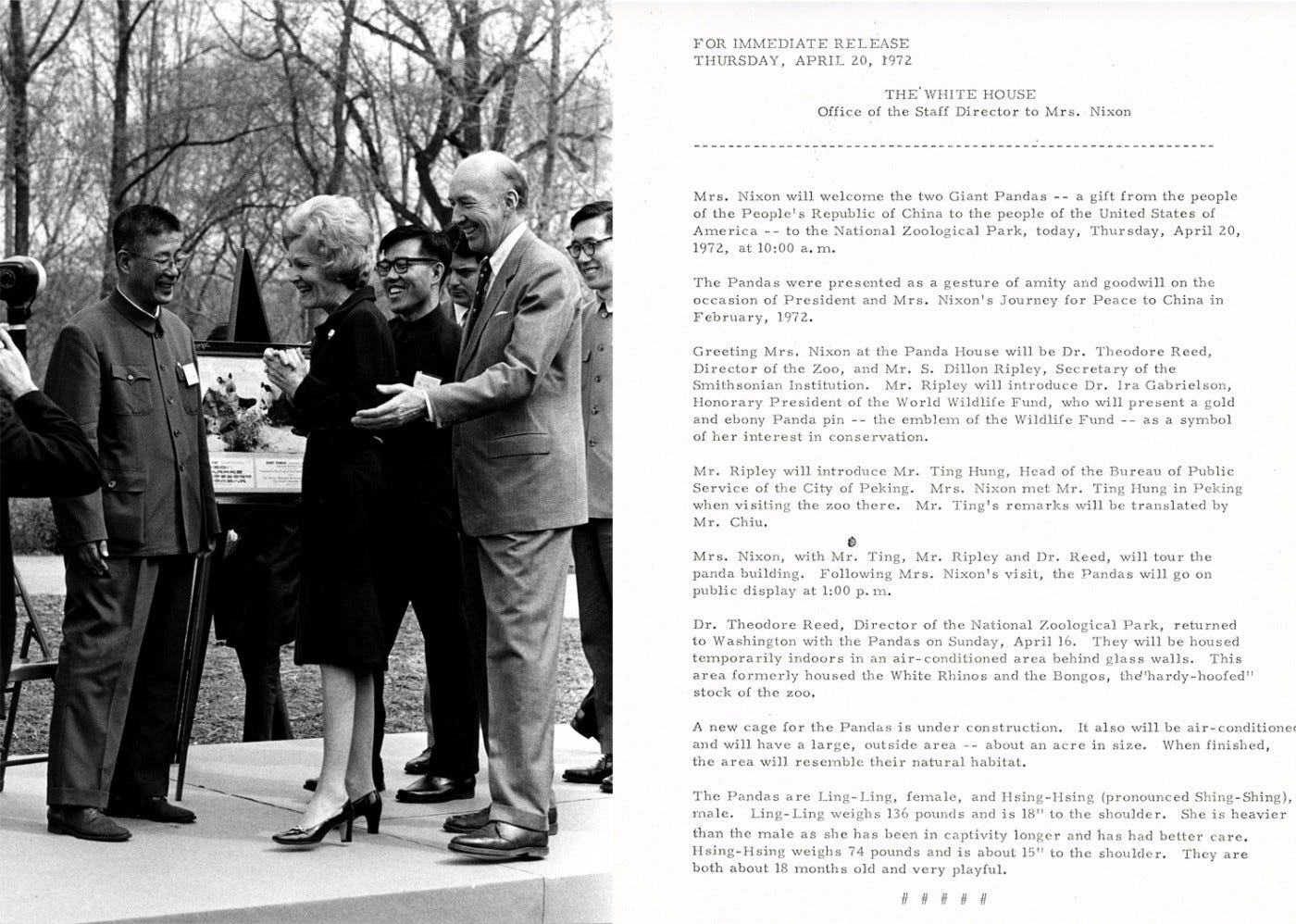

The United States has a special place in the history of panda diplomacy. It all goes back to 1972 when then-President Richard Nixon made his historic visit to communist China. During a dinner in Beijing, First Lady Pat Nixon mentioned her fondness for giant pandas. As a gesture of goodwill following the visit, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai gifted two giant pandas, Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing, to the American people.

This marked the start of a unique bilateral relationship. Over the next two decades, Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing produced several cubs, even though, sadly, none of them survived for long. Future cubs would arrive in the United States as a sign of appreciation for its continued trade partnership with the United States. The story of these pandas is intertwined with the broader concept of bilateral agreements, the same kinds of agreements that have a profound impact on international trade.

Trade Pacts and Diplomatic Dilemmas

While pandas are at the center of this diplomatic spat, they represent a much bigger policy problem. At the heart of panda diplomacy lies the intricate establishment of bilateral trade agreements. Like the agreements to bring pandas to countries, trade agreements are negotiated to create a favorable environment for the exchange of goods and services. These agreements seek to reduce trade barriers, encouraging more imports and exports. Their goal is to foster a relationship that ensures gains from trade for both countries.

Without these agreements, countries may be tempted to impose tariffs and import quotas on other countries in an effort to prop up domestic production. These policies can be particularly tempting whenever the trade balance between two countries appears to favor one nation more than the other. Those policies, however, end up reducing each country’s overall well-being. Bilateral trade agreements exist to counteract the pressure to disrupt the temptation to impose restrictionist policies.

The Intersection of Trade and Diplomacy

Pandas are a symbol of friendship and goodwill, but they also serve as economic assets in the world of international diplomacy. The decision to recall pandas from other countries isn't just a diplomatic move; it's also infused with economic considerations. In a way, it's China's way of saying they might not be very happy with how things are going in their diplomatic relationships.

Panda-monium Awaits!

In the grand scheme of the economy, the recall of pandas will largely go unnoticed. The animals serve more as a symbol of diplomacy than a driver of economic growth, but the individual zoos themselves may feel differently about what’s ahead. Zoos often invest substantial resources in housing and caring for pandas, which can boost visitors and generate revenue for the zoo. There is a certain reputation that comes with being one of the few zoos in the world that cares for pandas, but that reputation may be tarnished through no fault of their own.

So, as we await the panda-monium that will inevitably hit The National Zoo and Zoo Atlanta, it’s a chance to keep our eyes on trade relations between China and the United States. The appeal of the giant panda is only a metaphor for the intricate connection between diplomacy and economic interests. It's a lesson in international trade, where even the softest of powers can yield significant influence.

Animal diplomacy isn’t limited to pandas, Australian politicians have used koalas to cement international ties [Daily Mail]

Ling-Ling passed away in 1992, and Hsing-Hsing followed in 1999 [

There are about 1,864 pandas remaining in the wild, mostly in China's Sichuan Province [CBS News]

The Smithsonian's National Zoo in Washington DC attracts nearly 2 million visitors from all over the world each year [Smithsonian's National Zoo]

Pandas subsist almost entirely on bamboo, eating from 26 to 84 pounds per day [World Wildlife Fund]