And the Award Goes To…

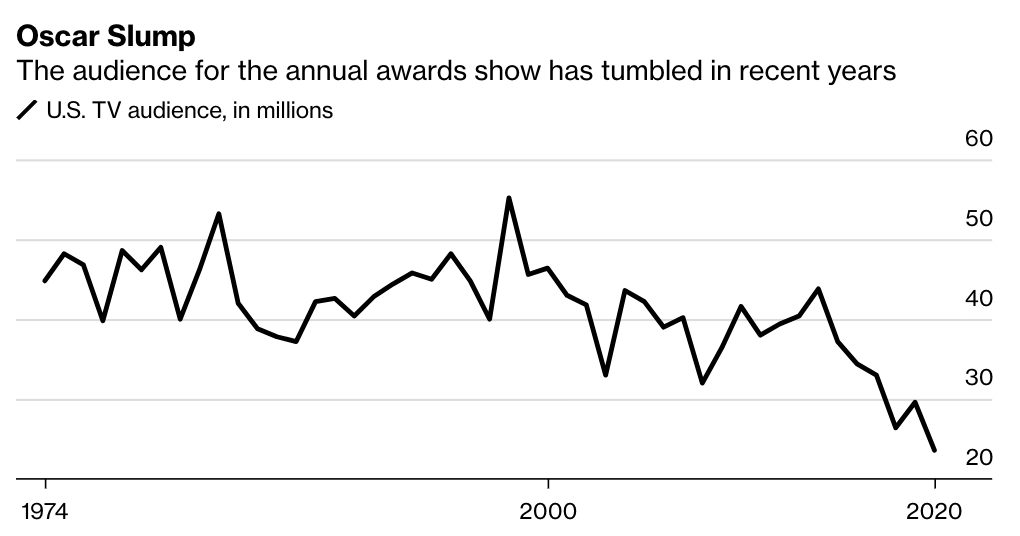

Did you catch the Academy Awards last night? If you skipped it for something else (or didn’t even know it was on) then you’re not alone. Last night marked the annual tradition of “Hollywood’s Biggest Night,” but viewership for the show has been falling for the past 6 years and hit a record low in 2020. ABC was seeking $2 million for a 30-second ad spot, but we won’t find out until later today whether the 93rd Academy Awards outperformed last year's historically bad mark:

We could see a new record-low turnout this year because the pandemic has crushed peoples’ ability to see the top films in theatres. Being nominated for an Oscar can have a significant impact on a film’s revenue, but winning doesn’t have all that much of an impact. Soul won the award for best-animated film despite now airing in a US theatre, but with theatres closed and people still worried about crowds, will the awards still have a significant impact? Movie theatres have done what they can during the pandemic to survive, but low box office numbers over the past year are a concern for Oscar viewership:

The concern for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is that low box office numbers generally translate into low telecast ratings. Viewers of awards shows like to have a rooting interest in the outcome, but audiences haven't seen this year's nominees, and the AMPAS worries they simply won't tune in.

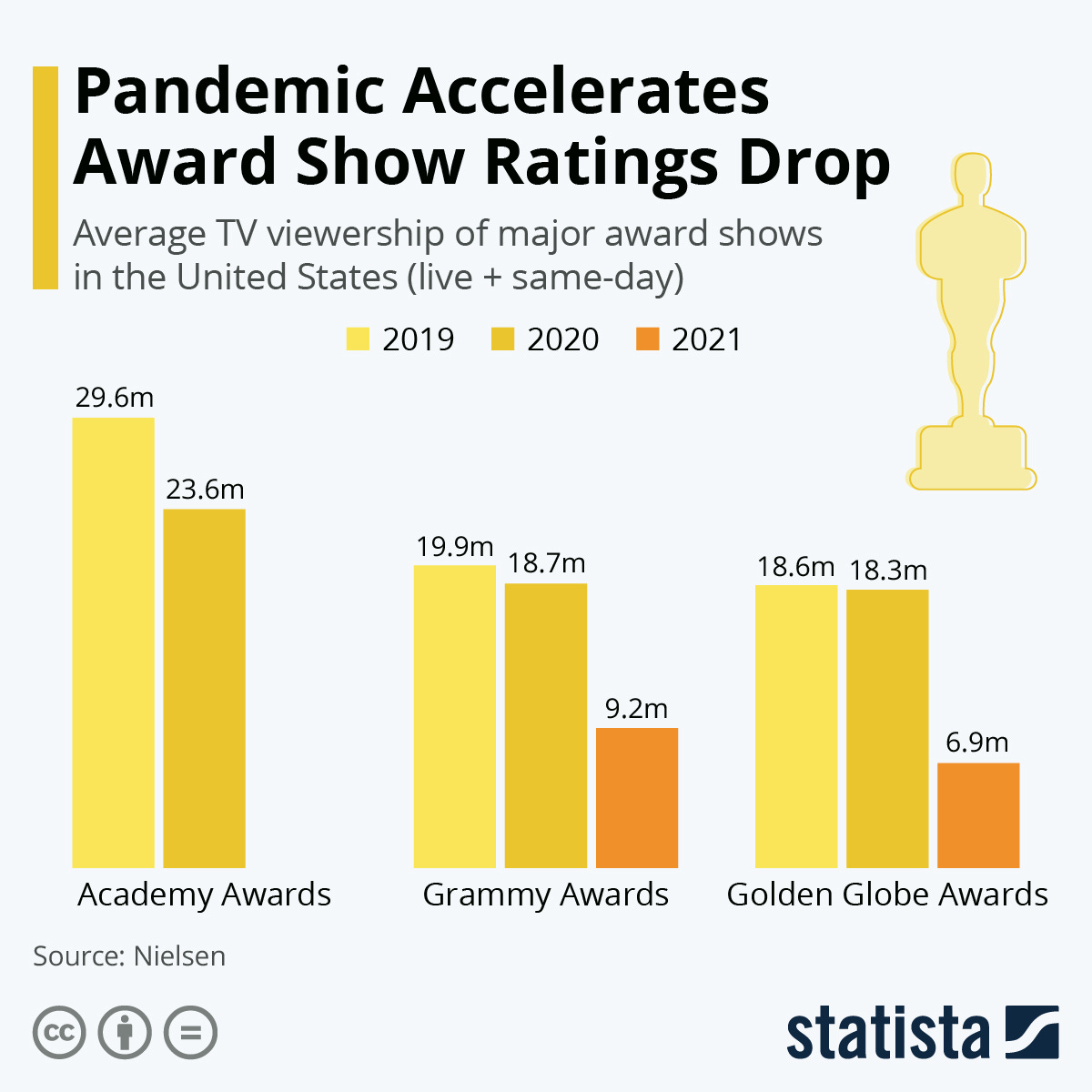

It doesn’t help that the Academy Awards are the third major award show during the pandemic. A January Gallup poll found that 56% of Americans are working remotely “all or part of the time,” but that isn’t translating to more people willingly sitting down at the end of the day and watching awards shows. Each of the previous major awards show saw significant drops in viewership:

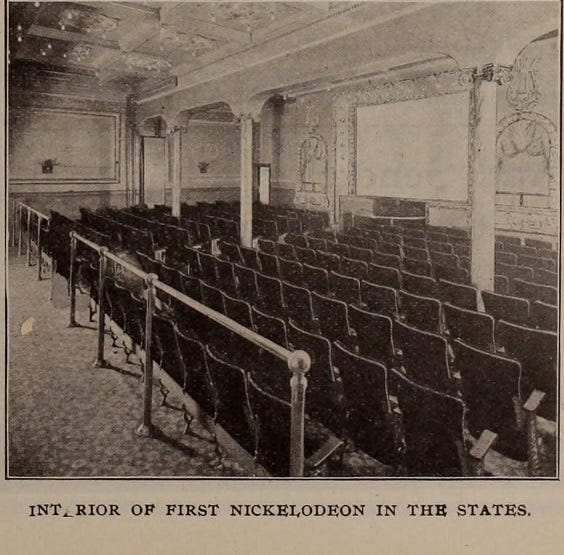

This history of the award show itself is rooted in economic incentives, much like the incentives of a tire company publishing a dining guide. The moving picture (silent films at the time) was revolutionary for America’s working class who couldn’t afford the “high class” entertainment with traditional theatre. The first motion picture theatre (known as a nickelodeon) opened in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on June 19, 1905, to a crowd of 450 people. By 1920, it was estimated that half of all Americans went to the movies each week.

The early pioneer of the industry was Louis B. Mayer, who immigrated to the United States from Russia and would eventually become part of the namesake merger that would produce MGM Studios in 1924. Before becoming a blockbuster Hollywood producer, Mayer and other studio executives needed to figure out a way to appease actors in the growing film industry. The industry was becoming clustered in California, and as films began to include sound (then known as talkies), the film industry was in search of more writers. Many of those writers moved from the East Coast, where unionization played a more prevalent role in the labor market.

Enter The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1927. One of their first acts was the creation of an awards ceremony to honor the work of their writers and actors who made it all possible. Their first award ceremony was in 1929, but the winners had actually already been announced 3 months earlier. The first ceremony was really more like an industry-wide dinner. Subsequent awards banquets would withhold the award information until the night of the banquet, and radio/television stations would eventually air the shows live for viewers at home.

Eventually, technology would disrupt the movie industry. Peak viewership for the Academy Awards occurred in 1998, just a year after Netflix was founded. Netflix started as a movie rental service shipping DVDs by mail. The streaming version we know today was started in 2007. Redbox, the automated DVD kiosk located outside your favorite Walgreens, started in 2002. Both companies have allowed families to consume movies in their own homes rather than at the local theatre. Blockbuster had its peak valuation in 2004 before ultimately failing after ignoring the impact of Netflix/Redbox.

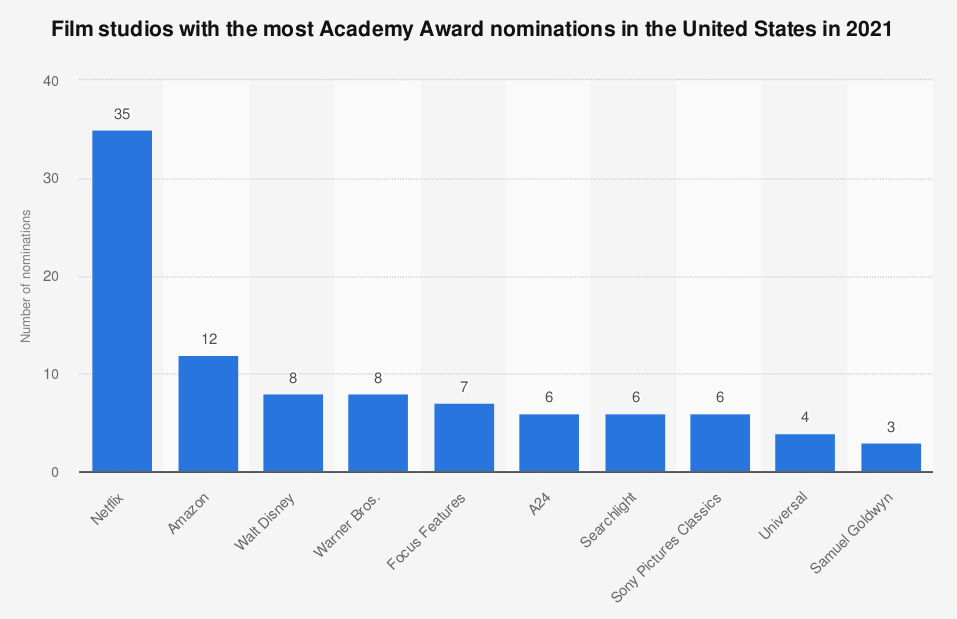

As Netflix morphed into a streaming giant, it began producing its own films. Their incentives for winning an award, however, aren’t the same as traditional studios. Studios like MGM care about customers showing up in the theatres, or eventually buying a copy of the movie. Netflix, however, wants more subscribers to its streaming platform and has spent a large portion of its budget on advertising to Oscar voters. Last night, Netflix topped other studios, including Disney, with 36 different nominations. They finished the night with seven Oscars.

With all the nominations (and wins!) that Netflix has garnered over the past few years, you may naively believe that Netflix is just producing at a much higher quality level. In addition to its long history of diversity problems, the Academy Awards are also heavily influenced by money. Studios spend a lot of money advertising directly to award voters through For Your Consideration (FYC) campaigns. Variety estimated that studios spent up to $10 million in 2016 to lobby voters. Spending that much doesn’t guarantee a film wins, but it does mean that the film will be considered, even if it isn’t the best film on the list of nominees. This award spending arms race has been openly criticized and there are calls for a reform of the process. For more on this rent-seeking behavior, check out this segment on Adam Ruins Everything:

Like any good award show, we’ll have to wait to find out whether this year’s show was the new historical low or if there was enough excitement to entice people to turn on the televisions. For a deeper look at the intersection of data and the Oscars, check out this piece in the Harvard Data Science review. While you wait, or if you want an alternative way to spend your Monday night, a team of economics researchers surveyed economics educators about the best films to teach economics. Check out one of the following from their top ten list:

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946 nominee for Best Picture)

A Beautiful Mind (2001 winner for Best Picture)

Moneyball (2011 nominee for Best Picture)

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013 nominee for Best Picture)

But before you go check to see if those movies are on your favorite streaming services:

The BLS estimates that there are 44,460 actors in the United States as of May 2020 [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

From 1984 to 2000, every single best picture winner was a drama [Frontier Economics]

Netflix has an estimated 208 million subscribers around the world [The Verge]

North American box office returns fell from nearly $11.4 billion in 2019 to $2.2 billion in 2020 [CNN]

We have finished Week 16 of 2021 and I’ve checked in 22 books so far. I have started reading a couple of fiction books to give myself a break from all the nonfiction I tend to read during the semester. As my Labor Economics class wraps up their semester, I finished my fourth reading of We Wanted Workers. Borjas is (in)famous for his work on immigration, particularly his stance on the Mariel Boatlift, and this book serves as a solid overview of his position.

The other book I finished was one of Austin Kleon’s books on promoting work and developing a following. I enjoyed Show Your Work when I read it a few weeks ago that I thought it was time I bought the other two. I’m really looking forward to Keep Going: