Where have all the low-wage workers gone?

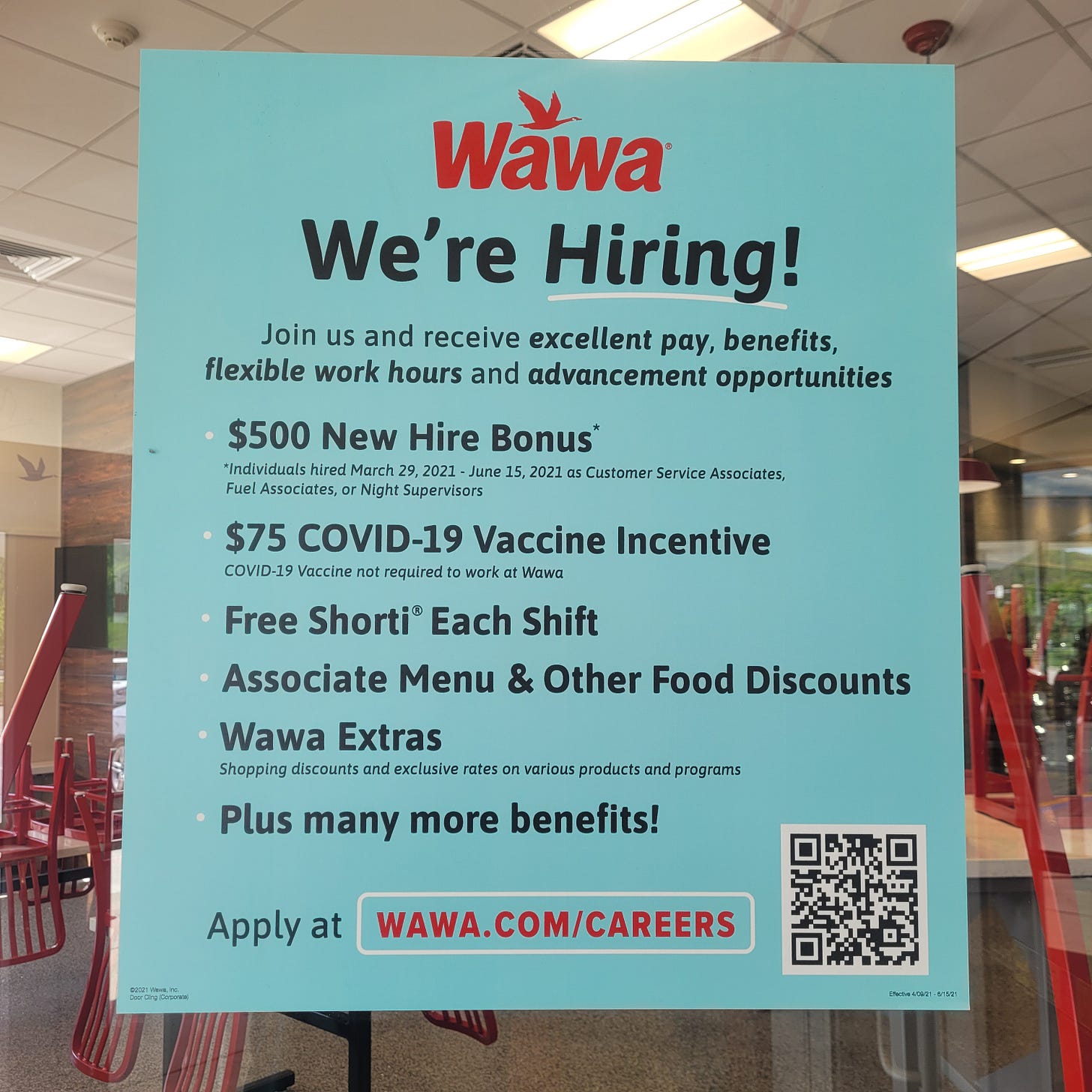

There’s a good chance that you’ve been to your local grocery store or stopped by your favorite fast food location and noticed signs for hiring bonuses. Similar programs have been in place for years, well before the pandemic began, but they’ve drawn extra attention over the past few months as companies struggle to find enough workers to fill low-wage positions despite the unemployment rate still above 6%. On a recent stop at Wawa, I caught a glimpse of this sign:

You may look back on the past year and not be all that surprised that low-wage workers aren’t rushing to get back to their jobs. Shutdowns and restrictions during the pandemic cost the economy about half a million jobs in the hospitality, travel, and retail industries. As businesses begin to reopen and restrictions are lifted, many workers aren’t willing to trade their safety and mental health for $10 per hour. It’s easy to place blame on recent policies like expanded unemployment or the stimulus. And while those programs likely impact some aspects of the market, there has been a “shortage” of low-wage workers for years. A recent article from Eater highlights some of the debate around where to place blame. Here’s just a piece:

Managers and owners are largely blaming their inability to retain — or even re-hire — staff on expanded unemployment benefits designed to mitigate the economic devastation of the pandemic; claims that “no one wants to work” because they’d rather stay home and cash unemployment checks have become commonplace, even though they aren’t entirely accurate.

It’s hard for people to look inward and place some of the blame on themselves. Low-wage occupations are seeing increased demand from customers while simultaneously seeing portions of their workforce not come back. Correlation, however, isn’t the same as causation. Given some of the articles coming out of restaurant-themed newsletters, this may be a situation where workers are expecting some sort of compensating differential for the new additional risk. A compensating differential is additional pay for an unpleasant working condition (like risk) that isn’t present in alternative employment.

An obvious risk now is the likelihood of dying. A study by researchers at UC San Francisco looked at death certificates for Californians age 18 to 65 during the first seven months of the pandemic and compared the death rate to pre-pandemic rates. The researchers found an overall increase in mortality of 22% during the pandemic. Line cooks had a 60% increase. Bakers were also part of the top 5 occupations with over a 50% increase in mortality rates.

For workers in that industry who have been unemployed, it’s given them time to reconsider if it’s an industry they want to go back into. Labor practices in this industry have been notorious for creating unpleasant working conditions, like asking employees to close a store at night and then come in the very next morning to reopen the store, setting schedules for workers only days in advance, or the erratic pay associated with occupations that rely on tips. Typically, compensating differentials would imply that additional compensation needs to be present in order to incentivize workers to join that particular industry. It seems that a few extra dollars per hour, while relatively larger than their previous pay, aren’t enough for workers to accept the added risk. If firms don’t want to increase pay, the alternative is to reduce the unpleasantness of the job.

Some business owners that employ a large number of low-wage workers balk at the idea that their company can afford additional pay for their workers. While I was searching for additional stories to link in this post, I decided to search for Chipotle’s CEO Brian Niccol. The “Top Stories” turned up three interesting headlines, and the juxtaposition couldn’t be more telling of the issues facing the industry:

National policies in the past have talked about the importance of “upskilling” and guidance counselors have encouraged students to avoid “low skill” work. The problem with each of these approaches, and others who use the term “low skill,” is that they often are talking about a wide range of occupations, many of which require a sufficient amount of knowledge and aptitude. Many of the jobs people previously called "low skill” have been labeled as “essential” during the pandemic. In a sudden moment, Americans realized the importance of these jobs in the overall economy. Recognition, however, doesn’t seem to be enough to overcome the stress of working in low-wage occupations.

As of April 2021, the BLS estimates that there are approximately 14,067,000 employees in the Leisure and Hospitality industry [FRED]

The median wage (including tips) for waiters and waitresses is $11.42 per hour [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

The quit rate in the Leisure and Hospitality industry hit a 20 year high in December, at 5.2% [FRED]

We have finished Week 19 of 2021 and I still have only checked in 25 books. The past week has been a little hectic, so I haven’t finished any new books. If you’re looking for an interesting book based on the topic of this week’s newsletter, I’d recommend Fast Food Nation. It looks at the “dark side” of fast-food employment. It was written in 2001, but you’ll likely recognize some of the same themes today.

So why haven’t I finished any books this past week? A couple of days ago I flew to Frisco, Texas to watch my alma mater win their first national championship! It’s been an emotional weekend for sure.

I want to thank you for taking the time to read today’s post. If you have any comments/feedback, please feel free to leave a comment below. If you are enjoying what you’ve read, please share Monday Morning Economist with others. —Jadrian

To the best of your knowledge, have there been any examples of a similar scale event drastically reorganizing wages for an industry? I would be really curious to learn more about that scenario if it exists.

Really good post. I am surprised that most commentary about wages and unemployment has neglected the compensating differential possibility. Thanks for providing me with content to share when I make the argument.