The Rise, Fall, and Comeback of Kodak

The rise and fall of an American tech giant is just an example of creative destruction. Its resurgence may signal its new role as a vintage offering.

Last week, Kodak announced that demand for 35mm film has exploded over the past few years and that they’re in the process of hiring hundreds of employees to keep up. Aside from a great example of labor being a derived demand, it’s also an opportunity to explore how technological change has impacted the photography industry. Firms adjust their hiring practices as demand for products and services changes, but that demand is also impacted as new products replace older ones.

The photography industry over the past century has been a rich example of creative destruction. The concept was developed by Joseph Schumpeter and discussed in his 1942 book, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. He argued that markets constantly evolve as newly created products replace older ones. This innovation transforms markets in ways that save people time and money, and thereby improve standards of living. Some businesses will inevitably fail as they are replaced by more innovative companies, but the net positives for society outweigh the cons.

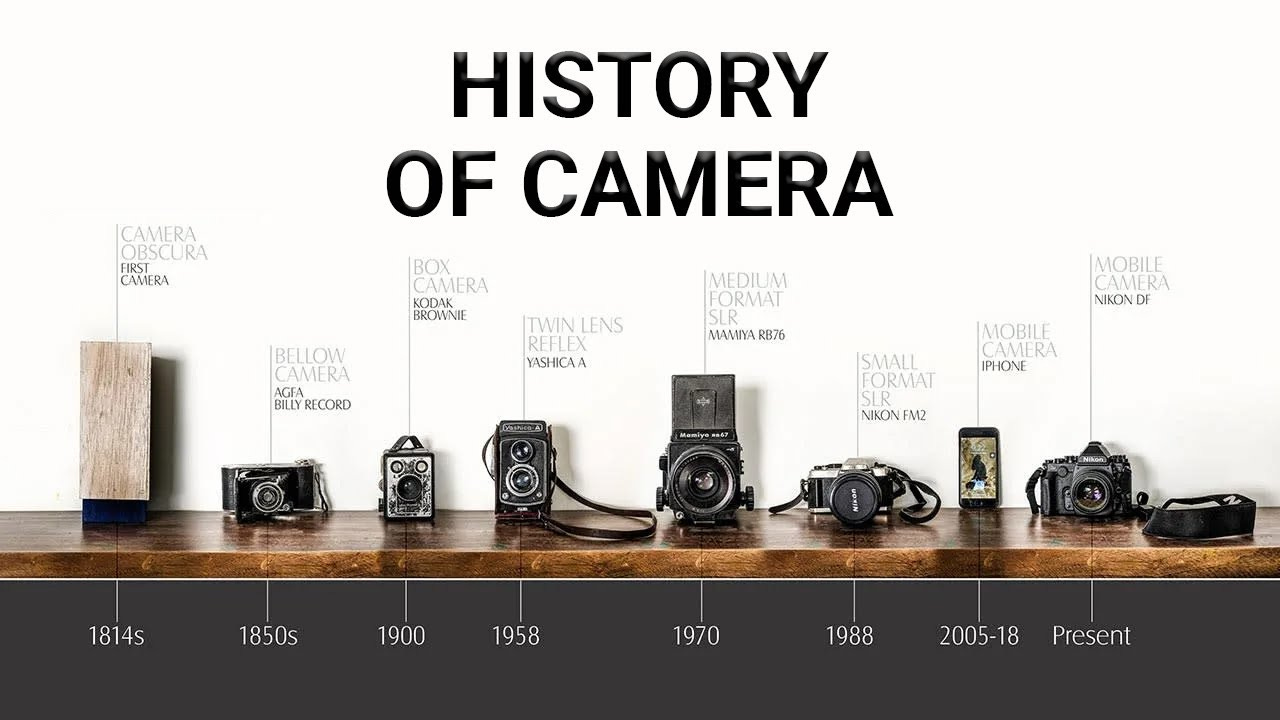

In the late 1800s, George Eastman became one of the first people to successfully manufacture dry plates for commercial sale in the United States. A few years later, the Eastman Kodak Company introduced the first commercial transparent roll film. The original Kodak Camera would sell for $25 and include 100-exposure film. If we convert that value to today’s dollars, the camera would cost about $884. Once the film was used up, the camera could be sent back to Kodak and it would be returned to the owner with fresh film, the original negatives, and mounted prints all for a cost of $10.

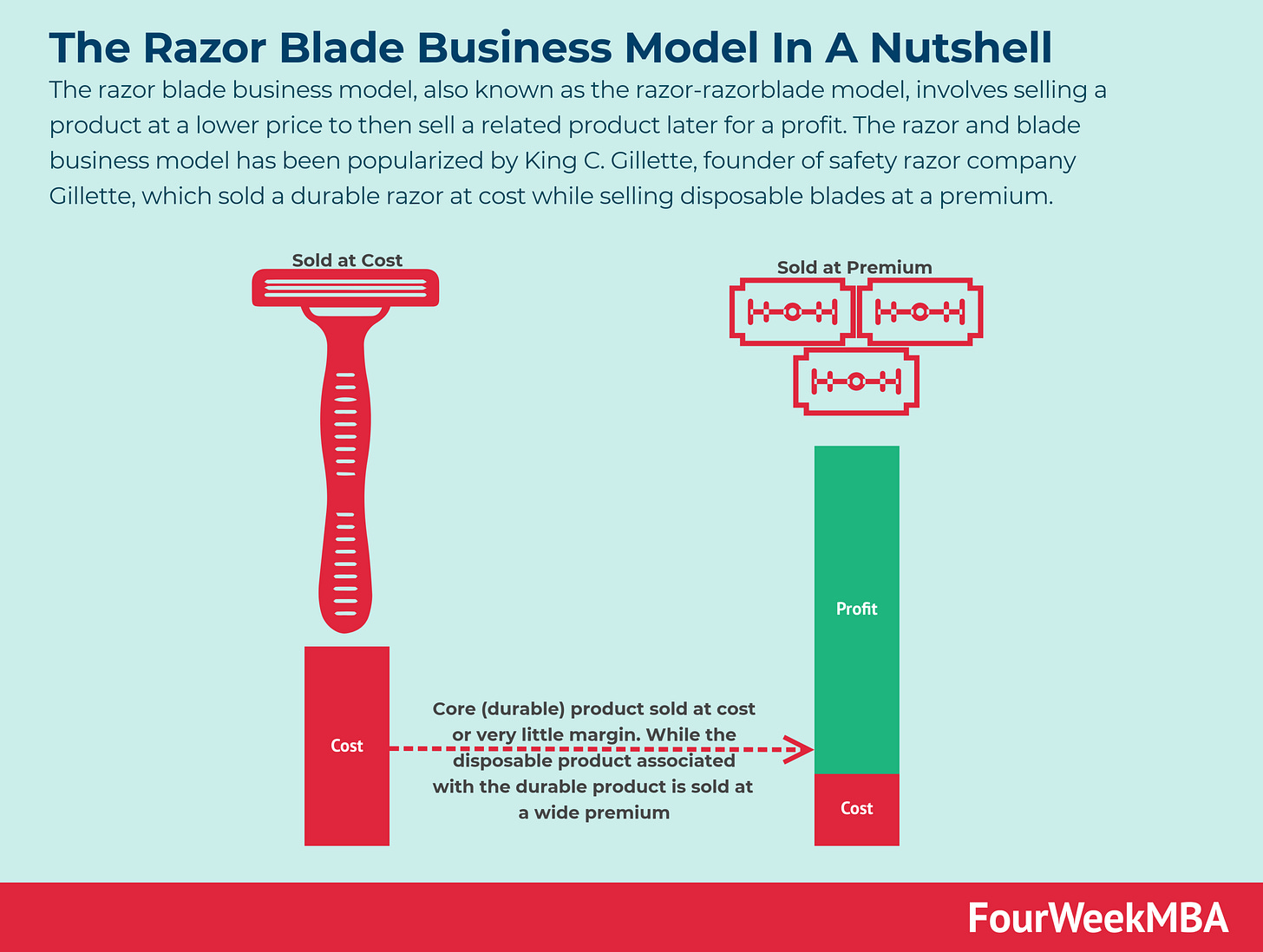

Eastman developed a pricing strategy that we know today as a two-part tariff. Under this model, a firm sells multiple products that are bundled together by the consumer. For one of the products, the firm operates competitively with other companies to be the main provider for the customer. Once the firm has captured that customer, they operate as a monopolist by being the only firm selling related products that customers need to use with the original purchase. In the marketing world, this is known as the razor and blades model, which popularized the same sales strategy that Kodak had been using before Gillette was founded.

The competitively priced product is usually some sort of fixed item for the consumer, like the camera itself or the handle on a razor that has replaceable blades. Once a consumer picks their favorite brand of the fixed item, the firm sells the related items at a monopoly markup since the fixed products are typically designed to function with the firm’s related items. The consumption of those related items varies by customer depending on how much they plan to use it. High-frequency users will buy a lot of related products while casual users will buy a lot less. If someone purchased a Kodak camera, their camera would only work if it had Kodak film loaded into it. Most modern razor blades have been designed to only work with the same brand’s replacement blades.

There are plenty of other products that follow the same pattern of selling a fixed component at a competitive price and the frequency component sold with a monopolistic markup. You see similar pricing decisions for products like printers and ink cartridges, Barbie dolls and her clothes, and even gaming systems like Playstation and its digital games. The fixed item can seem affordable compared to the alternatives because alternatives usually exist. The pain point comes when buying the related items since there aren’t any competitors.

In the 1880s, photography was a generally expensive hobby. In 1900, the Kodak Brownie Camera was introduced and brought photography within the financial reach of everyday consumers. The camera sold for $1 and the film was 15 cents a roll. Kodak would go on to dominate the film and camera industry throughout the twentieth century. At its peak in the 1970s, Kodak was estimated to be responsible for 90% of film sales and 85% of camera sales in the U.S.

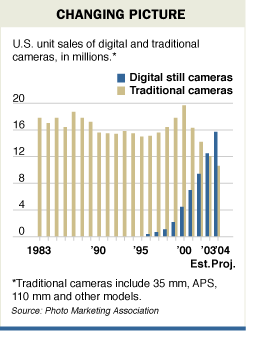

Kodak would eventually develop and patent the first handheld digital camera in 1975, but it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that digital camera sales really took off. As sales grew, traditional film sales slowly declined. While Kodak had a strong presence in the film and camera sector, there were many more competitors for digital cameras. A January 2004 Wall Street Journal article announced that Kodak would stop reloadable film-based consumer cameras in the U.S., Canada, and Europe by year's end. Here’s an early infographic from that article highlighting traditional camera sales (in beige) and digital camera sales (in blue):

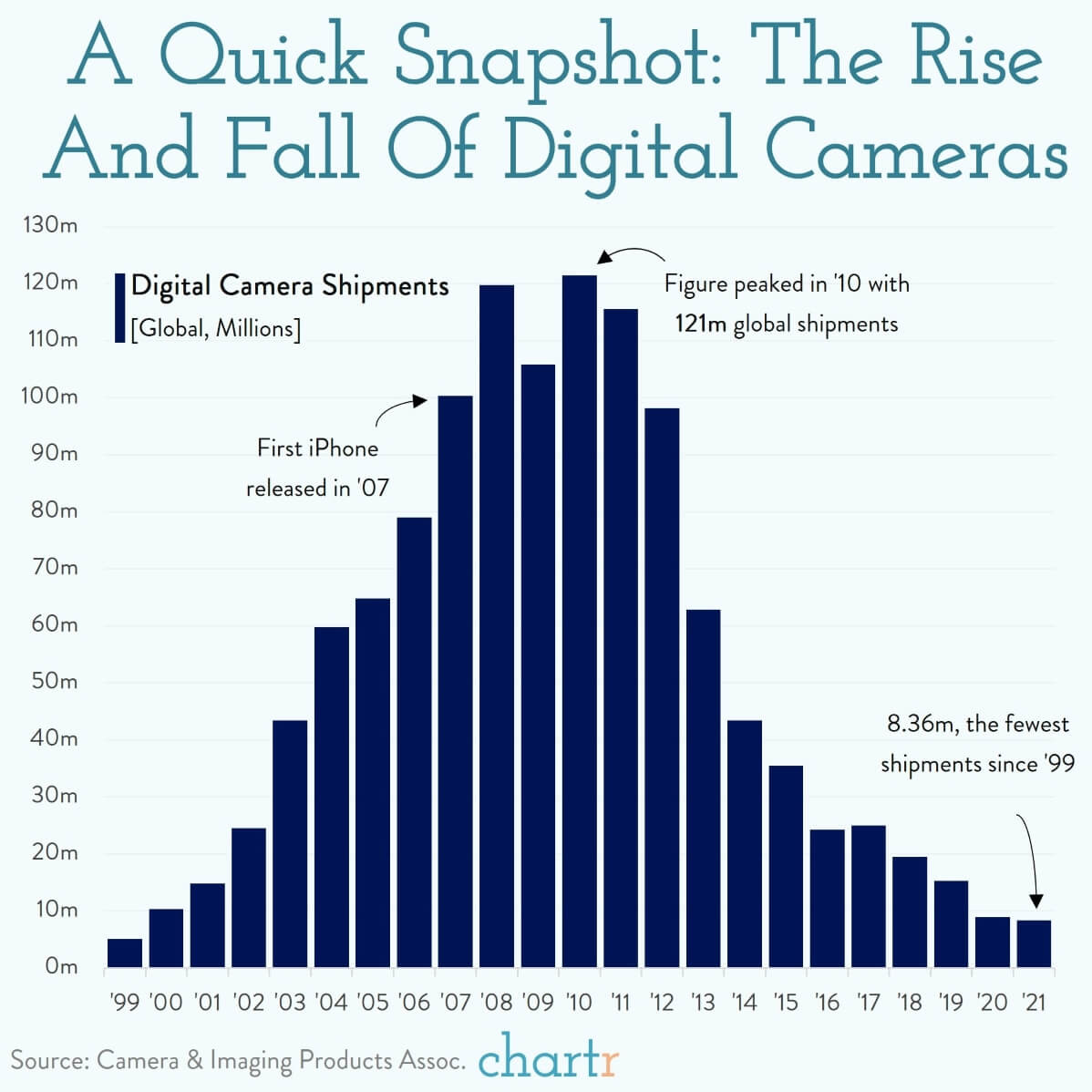

Like all good things, the digital camera’s fame would peak and wane too. Schumpeter argued that creative destruction was inevitable. New products come on the market to replace older products, but eventually, another innovation will replace what was once considered an innovative product. The bottom line is that no product is safe for the evolution of technology. Digital camera sales would eventually peak in 2010 and then begin a fairly rapid fall. Sales in 2021 were the lowest since 1990:

The culprit was likely the smartphone as Apple launched the first iPhone in 2007. As smartphones developed increasingly better cameras, the need for an additional digital camera fell quickly. While it’s hard to imagine anything more innovative than smartphones, creative destruction ensures that something, eventually, will replace the smartphone.

Creative destruction is largely focused on products and technology that affect the masses. There will likely always be a significant enough portion of the population interested in using an older technology. This isn’t always just a cranky person unwilling to adapt. Some products that were once the global leader can eventually come back in the form of vintage product lines. Polaroid cameras and vinyl records also peaked in popularity in the 1970s but have seen recent revivals.

A similar trend may be happening with Kodak. The company was one of the preeminent businesses throughout the 1900s and its headquarters in Rochester, New York employed tens of thousands of workers at its peak in the 1970s. Creative destruction means that entire industries and firms are susceptible to bankruptcy once a new product replaces the older one. Kodak would file for bankruptcy in 2012 and today employs around 4,000 people in total. Perhaps the recent announcement about increased demand for 35mm film is the signal that Kodak cameras have made their way back as a vintage hobby like polaroid cameras and vinyl records.

Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy is the third most cited social science book published before 1950 after Karl Marx’s Capital and Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations [London School of Economics Blog]

At its peak in 1982, Kodak employed 60,400 people in the greater Rochester area [NPR Marketplace]

By 1999, Kodak was the second largest maker of digital cameras, but they lost $60 on each unit sold [Kodak]

You can buy a waterproof digital camera at Target for about $50 [Target]

Vinyl records generated $1 billion in sales in 2021, which accounted for 6.9% of total industry revenue [Recording Industry Association of America]