Understanding These 3 Behavioral Economics Concepts Can Improve Your Life

Let Daniel Kahneman's groundbreaking contributions encourage us to really think about how we think.

You are reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of more than 4,200 subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or becoming a paid supporter:

Before we explore how our minds make decisions through the lens of a late Nobel Laureate, let’s start with a potentially familiar scenario. Perhaps you’ve got your eye on a brand new book priced at $30, but a quick online search shows that you can get a copy for $25 at a store that’s 20 minutes away. For many of us, the decision is a no-brainer—hop in the car and claim that $5 saving.

But consider how you might behave with a different purchase instead. Let’s say you’re about to drop $1,000 on a new television, but not before you spot an opportunity to save $5 by making the same 20-minute drive across town to a competing store. Suddenly, the prospect of saving $5 seems a lot less enticing.

Why do we value saving $5 on a new book differently than saving $5 on a high-ticket item like a television? This behavior seems at odds with our understanding of rational economic behavior, but perhaps it’s not so odd when we consider how behavioral economists explain the decision. The difference in behavior is an example of mental accounting, a term that was influenced by the late Daniel Kahneman, whose brilliance we’re celebrating today. Kahneman, who passed away on Wednesday, March 27, wasn’t your typical economist. In fact, he never took an economics course in his life.

Kahneman’s work often highlighted the irrational ways humans made decisions. Using examples like the one above, he showed how people compartmentalized their finances into different "accounts" in their minds. We tend to evaluate financial decisions on relative terms rather than absolute terms. It’s a simple, yet powerful demonstration of mental accounting at work.

The Man Who Mapped the Mind

Daniel Kahneman was born in 1934 in Tel Aviv, but he spent his childhood in Nazi-occupied France. As a Jewish child, he was forced to wear a Star of David on his clothing and abide by a 6 PM curfew. In 1944, he lost his father due to improper treatment of diabetes. After this loss, Kahneman’s family relocated to British-controlled Palestine, setting the stage for his eventual path into psychology.

After earning a psychology degree from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Kahneman’s service in the Israeli Defense Forces sparked his fascination with the psychological aspects of decision-making. While evaluating candidates for officer training, Kahneman and his unit struggled to forecast markets of success. This experience inspired him to introduce the term “illusion of validity.” This concept, emphasizing our overconfidence and its role in decision-making errors, would become fundamental in the study of cognitive biases.

Kahneman moved to the United States to pursue his Ph.D. in Psychology at UC Berkeley. He would eventually meet Amos Tversky and change the way the world thought about decision-making. Together, they began to question the basic assumptions of economic theory, speculating about the nature of economic decision-makers. They wondered: What if the notion of perfectly rational agents in economic models was unrealistic? What if, instead, these agents were as prone to errors, biases, and irrationality as any other person? It’s a question that economists are still curious about today.

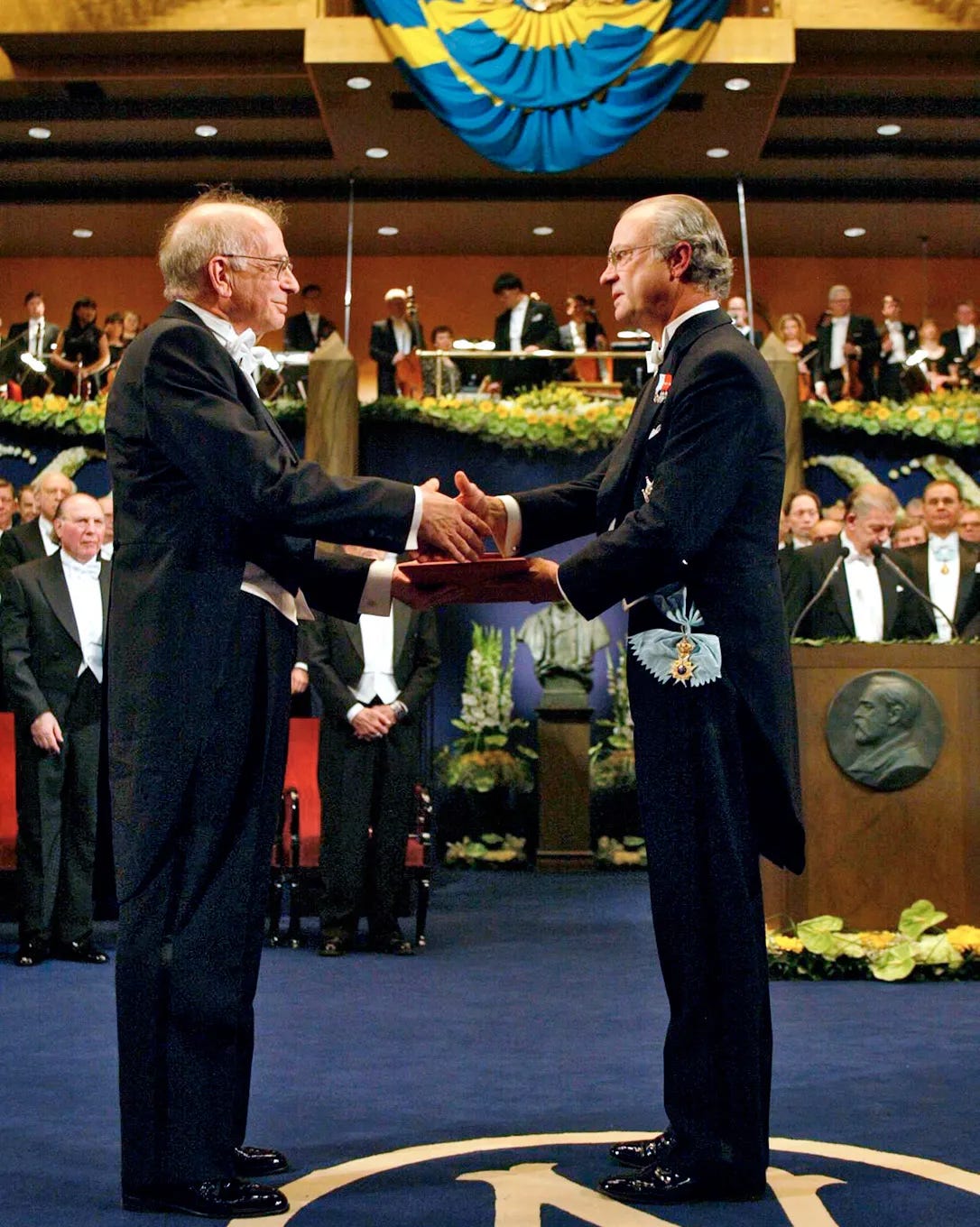

Nobel Laureate and Pioneer of Behavioral Economics

Let’s take a moment to recognize a special moment in Kahneman’s successful career: winning the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. This award acknowledges the impact of his work “for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty.” His work would lay the foundation for the discipline we now know as behavioral economics.

In this field, the messiness of human psychology meets with the rigor of economic theory, challenging the notion that humans can be perfectly rational beings. Kahneman’s research shows the ways that real-world decisions differ from the calculated choices predicted by traditional economic models.

Reflecting on Kahneman’s contributions, Harvard psychologist and author Steven Pinker highlighted the essence of his impact on our world:

His central message could not be more important, namely, that human reason left to its own devices is apt to engage in a number of fallacies and systematic errors, so if we want to make better decisions in our personal lives and as a society, we ought to be aware of these biases and seek workarounds. That’s a powerful and important discovery.

Steven Pinker’s insights capture the core of Daniel Kahneman’s contributions: the importance of acknowledging the shortcuts our minds take and the potential errors these shortcuts can cause. In a world full of complexity, understanding the nuances of how we think is just as important as understanding the fundamentals of economics. Kahneman’s work encourages us to reflect, reevaluate, and ultimately improve our decision-making processes, whether in financial markets or our everyday choices.

3 Concepts to Help You Make Better Decisions

Although Kahneman’s achievements are remarkable, we’ll focus on three key ideas that deeply influence our daily lives. These concepts highlight some of the challenges of making decisions and provide strategies to enhance our personal and financial decision-making. Understanding these principles can help improve our life choices with more wisdom and insight.

Concept #1: Loss Aversion with Prospect Theory

Kahneman’s most notable work, prospect theory, revolutionized how traditional economists view risk and decision-making. Imagine you’ve been given the option of selecting from one of the following payouts: one option guarantees you $50, while the other option has a 50% chance of either doubling that amount or leaving you with nothing. Most people prefer the certain $50 over the gamble, even though mathematically, both choices have the same expected value. This preference illustrates loss aversion, a key aspect of prospect theory, demonstrating our inherent preference to avoid losses more than pursuing equivalent gains.

This concept affects more than just our financial decisions; it influences our career moves, our relationships, and other aspects of life, steering us towards safer, less risky options. By acknowledging this bias, we can give ourselves the confidence to go for opportunities that we might otherwise avoid.

Concept #2: Heuristics and Biases

Next, let’s consider Kahneman’s research on heuristics and biases. Picture your brain as an office overwhelmed with decision-making tasks. To keep up with it all, your brain uses shortcuts known as heuristics, which help quickly sort through the day’s decisions. However helpful this may seem, these shortcuts aren’t perfect and can lead to mistakes and poor judgments.

Take the availability heuristic for example: your brain gives more weight to information that’s easily remembered. For example, a recent plane crash report might make you think air travel is unsafe, even though data shows it’s one of the safest ways to travel. This heuristic skews your risk perception based on what’s most memorable, not necessarily what’s most accurate.

Recognizing these mental shortcuts can enable you to reassess your decisions more carefully. While completely avoiding these biases is nearly impossible, being aware of them and how they influence our thinking can lead to more informed and rational choices.

Concept #3: System 1 and System 2 Thinking

The key to fully appreciating Kahneman’s work lies in understanding his distinction between System 1 and System 2 thinking. This concept sheds light on why pausing to reflect often leads to better decisions. System 1 is our brain’s automatic, instinctive mode that operates without much deliberation. It’s what helps us get through daily tasks like avoiding obstacles or recognizing familiar faces. Despite its speed and efficiency, System 1 is susceptible to shortcuts that may result in judgment errors.

Then there’s System 2, the deliberate, analytical aspect of our thinking that kicks in for more complex problems requiring conscious effort. This mode is slower and demands more mental energy, but it’s essential for handling tasks beyond System 1’s reach, such as doing math or making strategic plans. Understanding how these two systems function and their respective strengths and weaknesses enables us to identify moments when we might be relying too much on System 1’s quick judgments.

The solution for many hasty or poor decisions is activating our System 2 for a deeper and more thoughtful analysis. This approach can help us get past the biases and mistakes that System 1 might lead us into. It can help us reach more thoughtful, rational choices that better serve our long-term goals.

Kahneman’s Contribution to the Modern World

We’re living in a world that is as complex as it is exciting. From the high-stakes world of global finance to the delicate workings of personal relationships, Kahneman’s work can help us make better decisions. He’s handed us the ultimate hack. The key to making better decisions lies within our minds, but only if we slow down and think about it.

Whether it’s recognizing the dual forces of System 1 and System 2 thinking, avoiding our tendencies to avoid losses, or rethinking our reliance on heuristics and biases, we’re better equipped to make rational decisions because of the work of Daniel Kahneman. Let his legacy encourage us to slow down and think about how we think. Behavioral economics doesn’t have to just highlight our mistakes. It can guide us to making choices that are smarter, kinder, and better for our community.

As of March 31, 2024, Daniel Kahneman’s work has been cited 526,860 times [Google Scholar]

Daniel Kahneman was awarded 1/2 of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, sharing the honor with Vernon Smith, who was recognized for his contributions to experimental economics [The Nobel Foundation]

Daniel Kahneman holds honorary degrees from 24 different universities [Princeton]

There have been effectively zero deaths per 100 million passenger miles traveled by air in the US each year from 2002 to 2020 [USAFacts]

I AM TOO