So, What (Economics Concepts) Can We See?

Can JoseMonkey’s detective work help us understand spatial competition?

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

Back when I lived in State College, there was a part of town that I lovingly called the “Burrito District.” If you stood in front of the Qdoba, you could spot a Chipotle on your right and a Moe’s off in the distance. Of course, a Taco Bell was holding down the other side of the street. It was a tortilla-wrapped triangle of Tex-Mex options, all stacked side by side.

A lot of people may see this as bad business. After all, why would a business owner want to set up next to their closest competitors? Wouldn’t it make more sense to spread out across town and scoop up the hungry customers on the other side of town?

But this behavior isn’t limited to burritos and tacos. Drive around even smaller cities and you’ll usually the the same behavior with home improvement stores (Lowe’s and Home Depot), pharmacies (CVS and Walgreens), and even coffee shops (Dunkin and... another Dunkin).

I started wondering just how prevalent this was, so I reached out to JoseMonkey to help me dig into this spatial mystery for one of the pairs listed above. It turns out that if you can’t easily pick up and move your business, you may as well keep an eye on your competition.

So, what can we see?

Wait, Who Is JoseMonkey?

When people normally reach out to JoseMonkey, they’re not asking about retail clusters. They’re sending a short video with a request to be found based on the clues around them.

He’ll scan the frames for clues. A faded sign in the background, a weird business combo, maybe just a sliver of skyline. He then cross-references it all with Google Earth, OpenStreetMap, and other online sources. Before long, he’s nailed the location. Occasionally, he goes as far as figuring out which parking spot the person was standing in when they filmed the video.

His videos are a great break from the usual brain rot found online, but his mission is rooted in online safety. For starters, he only searches for locations when the person in the video explicitly asks to be found. His goal is to demonstrate just how easy it is for people to give away their location without realizing it. After you finish this article, check out his TEDx talk on the topic.

But that gas station in the background? The traffic light? The particular mix of stores on that corner? It might look like anywhere, but that’s what makes it so useful for him. I’ve been a fan of his videos for a while. But as an economist, I started noticing something else in the background: the businesses.

Over and over, I saw similar things he did: a certain mix of stores that turned out to help find the location. A Domino’s, an Ace Hardware, and a Smoothie King all in one plaza? That’s not actually as common as you might think. But some stores have such a big footprint, like The Home Depot and Lowe’s, that it’s hard to see them on the same city block.

And that’s what got me thinking. If a city is big enough to support both stores, it’s probably big enough for them to be on opposite ends of town. But are they?

Not always.

So, I asked JoseMonkey to go on a side quest from his usual challenges. JoseMonkey, can you help me figure out how often Lowe’s and Home Depot set up shop near each other?

So What Can We See?

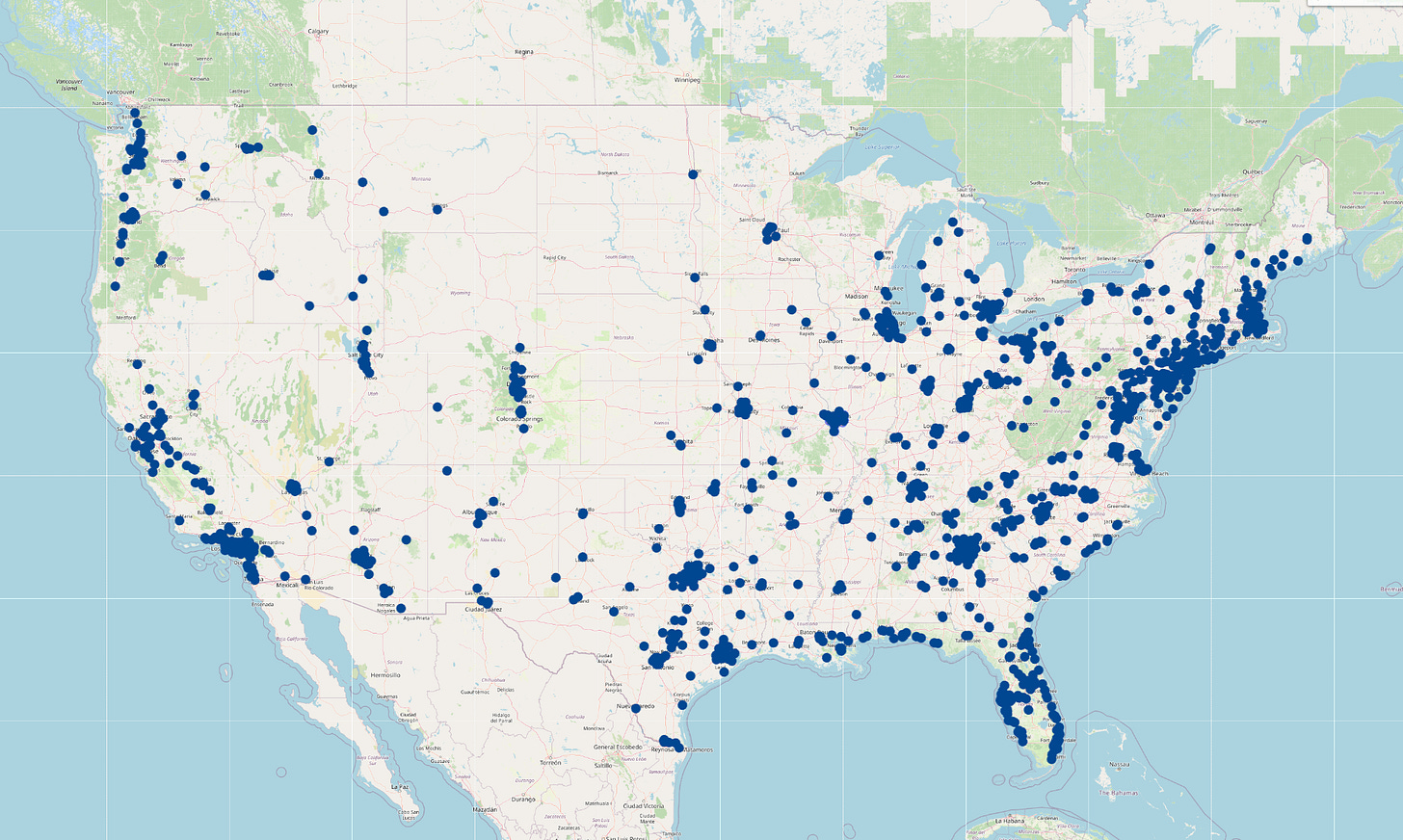

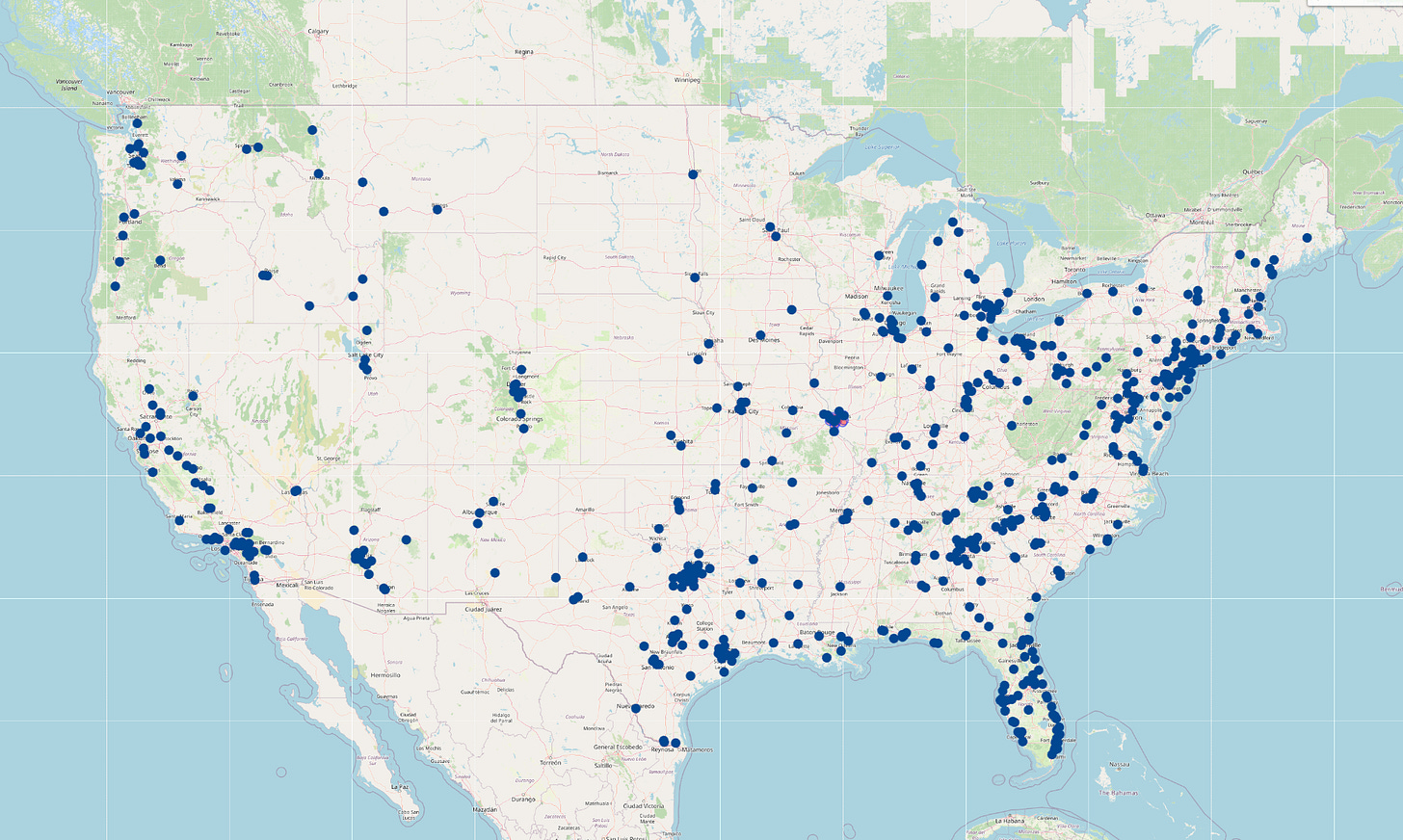

Let’s start with some data. There are more than 2,300 Home Depot locations across the United States. Lowe’s is a bit smaller, but still has around 1,750 stores across the country. If you didn’t know much about either company, you might expect them to spread out. Cities are big. Suburbs are sprawling. There’s plenty of room for both chains to claim opposite ends of town.

But that’s not what usually happens.

To find out just how often the stores locate next to each other, I asked JoseMonkey to use the same OpenStreetMap database that he uses to verify clues in his other videos. He started with all the Lowe’s locations listed in the database in order to then figure out how many have a Home Depot located nearby.

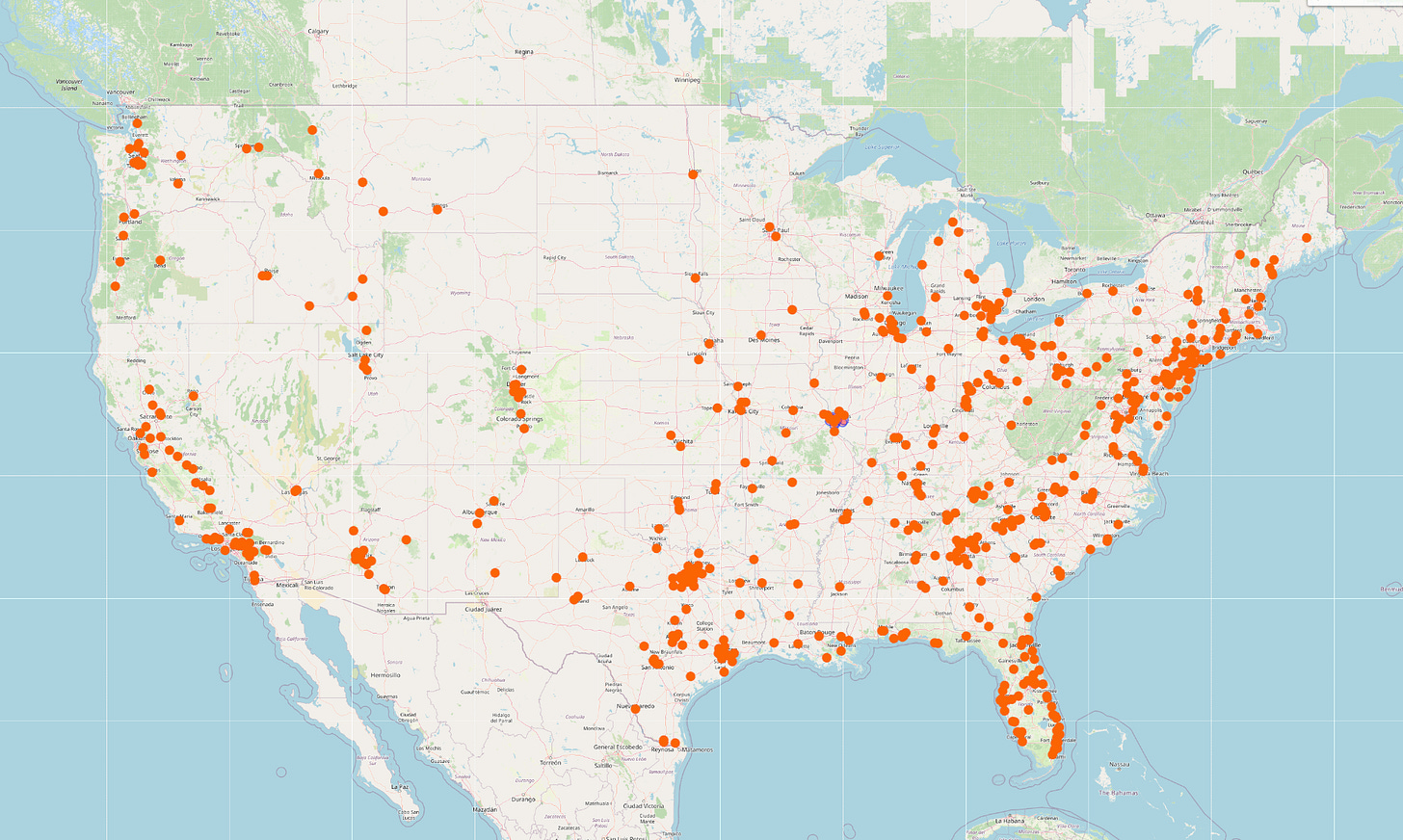

We started with a 5-mile radius around each Lowe’s location. It turns out that 1,206 of those locations have a Home Depot located nearby. That’s nearly 70% of their stores facing direct competition less than a 10-minute drive away!

But what if we narrow the radius down to just 1 mile? Even with that more restrictive radius, there are still 571 Lowe’s locations with a Home Depot as a neighbor. That means nearly 1/3rd of all their stores have their competitor’s bright orange sign in the visible distance (of course, that assumes there aren’t too many other signs in the way!).

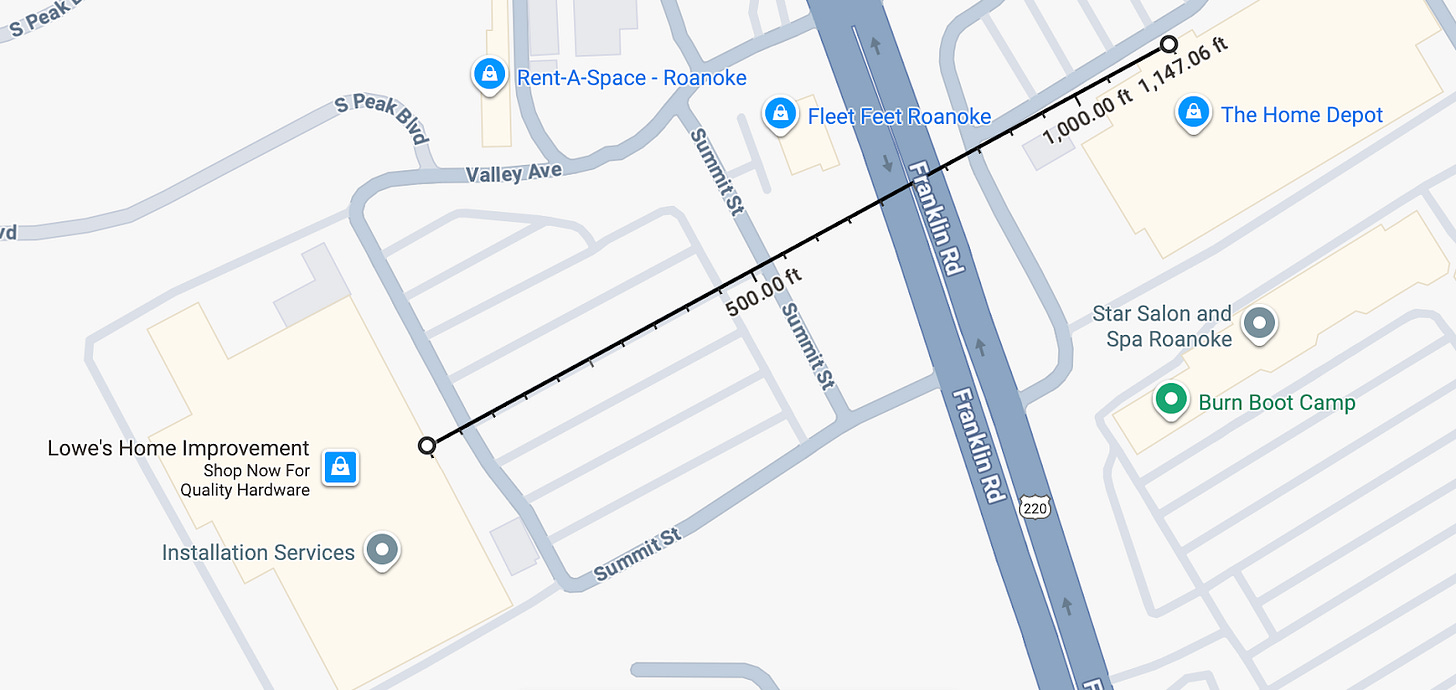

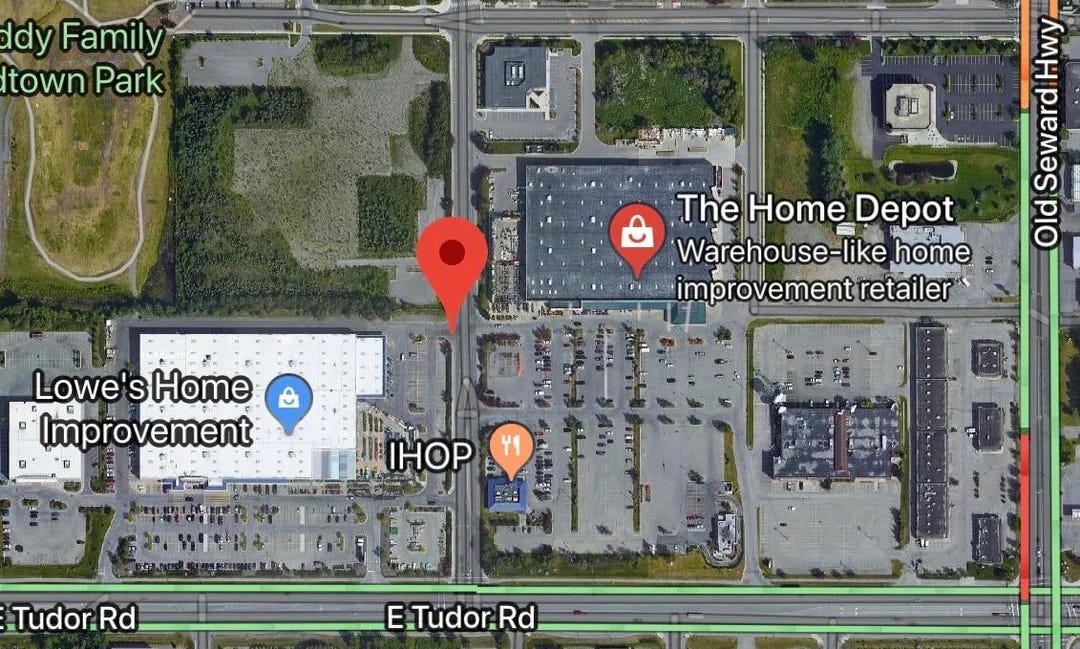

Can we zoom in further? How many locations are located less than 1,000 feet away from each other? That’s an easy walk in most cities! For example, here’s how close my local Lowe’s is to the nearest Home Depot store. Front door to front door, they’re just over 1,000 feet.

After all, these aren’t really corner stores like a Walgreens or CVS. They’re massive buildings with wide setbacks, multi-acre lots, and dedicated turning lanes. They’re not accidentally wedged together because it’s the only space available in a city. These are planned locations. And yet, there are 74 locations around the United States where these two competitors are located within about two city blocks of each other.

Remember, they could have chosen to set up on opposite ends of town. They could serve totally different neighborhoods and help residents avoid a 20-minute drive across town. But they don’t.

That’s what we can see, but now the question is… why?

The Economics of Clustering

There are dozens of Lowe’s and Home Depot stores located close enough for most people to spot both signs from either parking lot. Heck, there’s even a pair of stores in Alaska that share a parking lot! But here’s the thing: that’s not a fluke. Economists have been thinking about this behavior for almost a century.

Back in 1929, Harold Hotelling posed a deceptively simple question: If two businesses want to win over the most customers, where should they locate? To answer that question, let’s get out of the hardware store for a bit and head down to the beach for some ice cream.

Assume two identical ice cream vendors want to sell to sunbathers lined up along the shore. One sets up in the middle, and the other sets up way off to one end. Naturally, the middle vendor attracts more people looking for the shortest walk. So the other one on the edge inches closer the next day. Then the first one shifts slightly to block them. Back and forth they go until, eventually, both carts are side by side, smack in the center of the beach.

From the customers’ perspective, it’s really annoying. The average beachgoer has to walk more to get to the middle of the beach, but it really hits the people at the edge of the beach the hardest. But from the vendors’ perspective, it’s the only spot where neither has anything to gain by moving.

This is a type of spatial equilibrium. It’s not the most efficient outcome, but it’s the most stable. And when you zoom out to towns, cities, or even suburbs, you see the same basic logic playing out for all sorts of businesses looking to protect themselves from rivals who might steal customers away.

That’s why even in cities with plenty of space, some competitors still choose to cluster. It’s not because they have to, but because moving apart could leave them exposed.

Final Thoughts

Our ice cream vendors can easily move around to find the best location, but big-box retailers like Lowe’s and Home Depot can’t easily move around. Once they pour concrete, they’re in it for the long haul. That makes picking a location a long-term bet about where people will be living 10 or 20 years from now.

So if you’re going to take that bet, it might make sense to do it near someone else who’s taking the same one. In that sense, clustering is a hedge. If one side of town slows down, at least you’re not the only one stuck there.

Of course, the real world is messier than two ice cream carts on a beach or two home maintenance stores on the outskirts of town. That’s why Steve Salop expanded Hotelling’s idea in 1979. Instead of a straight line, he imagined a circle where businesses sell products that are similar, but not identical. It helps us better understand monopolistic competition, where firms compete not just on location, but on product differences, price, branding, and quality. A small shift around the circle can win over a whole new set of customers.

But location still matters. It shapes how businesses compete and how people like JoseMonkey can figure out where you are just by looking at what’s around you. Even if Lowe’s and Home Depot are clustered right beside each other in dozens of cities, it only takes one seemingly odd detail to give away the exact one. If you’re trying to blend in between two big-box stores, it’s best to make sure the rest of the scene doesn’t give away your location.

If this made you look at your local shopping center a little differently, consider sending it to a friend. While you’re at it, please follow JoseMonkey on TikTok or YouTube. You’ll never look at a street sign (or a strip mall) the same way again.

Lowe’s was founded in 1946 and Home Depot in 1978 [Investopedia]

Home Depot holds around a 17% share of the U.S. home improvement market, while Lowe’s has about 11% [Yahoo! Finance]

The average Home Depot store is approximately 105,000 square feet of enclosed retail space, with an additional 24,000 square feet for outdoor garden centers [The Home Depot]

About 45% of Home Depot’s total sales come from pro customers versus about 20% to 25% at Lowe’s [CNBC]

Reminds me of the median, voter theorem.

If you really want your mind blown, do a search on Advanced Auto Parts and AutoZone. The story I remember hearing was that a couple owned one of those stores, and then divorced. To spite their ex, one of the partners started a new auto store chain and tried to locate any new branch as close to the existing competing store as possible.

Great stack!! I remember watching that ice cream stand video in your class almost 10 years ago now