The Seen and Unseen Costs of a Hurricane

The final costs of Hurricane Fiona will likely be much higher than whatever number the government eventually comes up with.

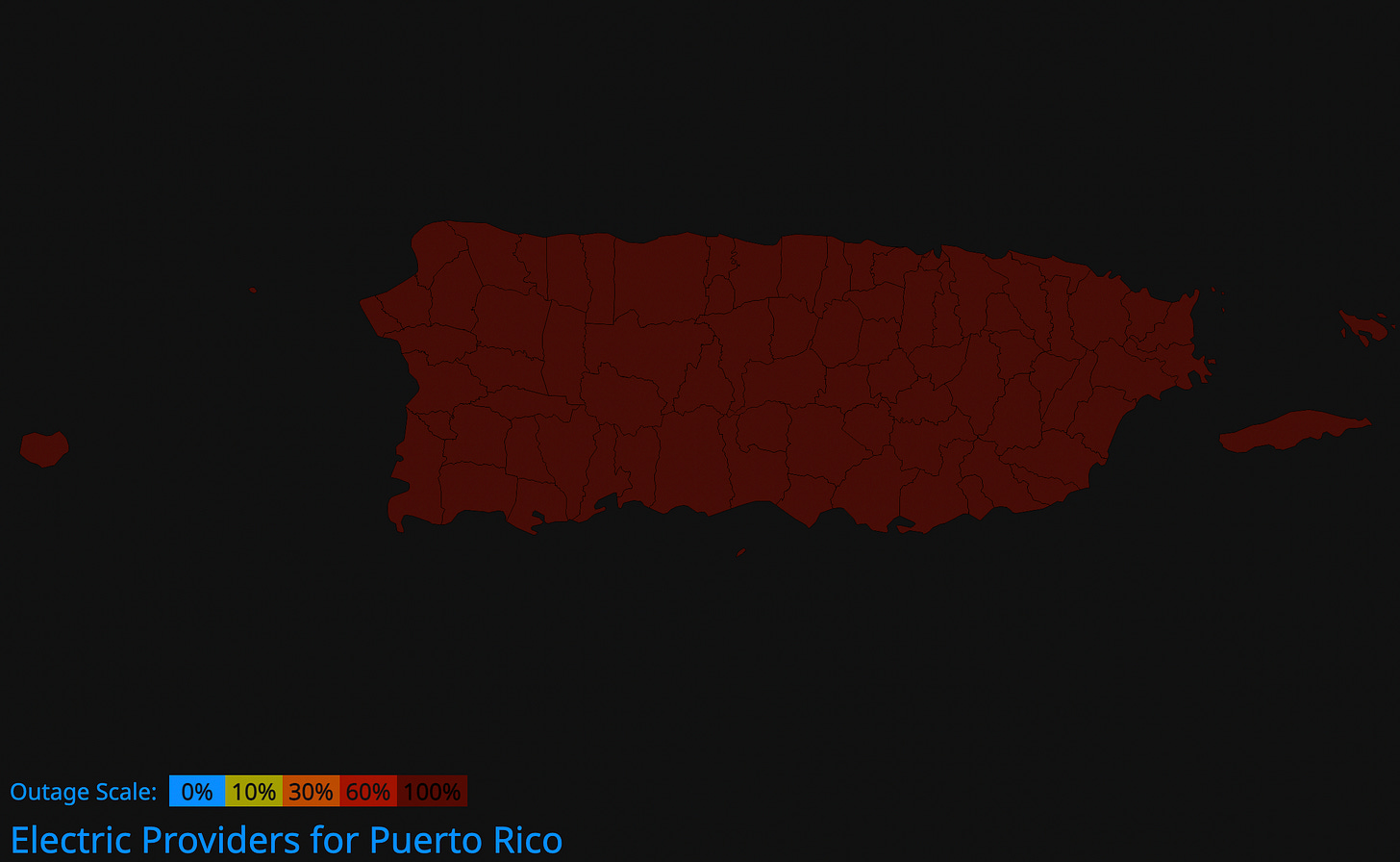

Hurricane Fiona landed on the eastern coast of the Dominican Republic this morning after knocking out power to the entire island of nearby Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico’s governor declared there have been “catastrophic” damages as nearly 1.5 million people on the island are without power as the storm moved through yesterday. Puerto Rico’s power company, LUMA, warned that full power restoration could take several days:

So far, the Atlantic hurricane season has had a quiet start with only three named storms between June and the start of September. While Hurricane Fiona will avoid most of the continental United States, it’s already leaving an impact on many Caribbean nations. Over the next few weeks, the government will start calculating the storm’s financial impact.

Calculating the cost is no easy task, but the National Center for Environmental Information (NCEI) serves as the official “damage calculator” for the U.S. government. The size and complexity of disasters influence how long it takes to assess the impact of disasters, and hurricanes are particularly time-consuming. For example, it takes more time to determine the impact of wind vs. water damage across assets than when a hail storm damages automobiles. When the NCEI calculates the final cost of a disaster, they include damage to things like:

Physical damage to residential, commercial, and government or municipal buildings

Material assets within a building

Time element losses like business interruption

Vehicles and boats

Offshore energy platforms

Public infrastructure like roads, bridges, and buildings

Agricultural assets like crops, livestock, and timber

Disaster restoration and wildfire suppression costs

The threshold for a severe event is $1 billion. So far this year, the US has 9 different weather and climate disasters that have eclipsed the $1 billion mark. Last year, there were 20 separate billion-dollar events in the United States with the average cost coming in at $21 billion. Tropical storms are often the most costly of the weather and climate disasters and the next couple of months will likely add some additional markers to the current map:

Some people (incorrectly) look at disasters of this magnitude as an opportunity to rebuild and invest in local economies. Those people would be falling victim to the broken window fallacy. It’s an easy trap to fall into, mostly because it’s an optimistic take on a negative event. The parable of the broken window was introduced by Frederic Bastiat in his essay "That Which We See and That Which We Do Not See." The argument goes that destruction is good for the economy because the money spent on repairs results in new production.

Bastiat, however, points out that “destruction is not profitable” because the money spent on repairing destroyed property is actually replacing something that was lost and not going toward creating additional value. The money spent after a natural disaster may increase GDP, but it does not increase national wealth. Had all of the original infrastructures survived, the additional money could have been used to create more or better services for people in the area. The same parable can be applied to other destructive events like war or crime.

Perhaps more interesting is what NCEI does not include in its cost calculations. The financial impacts they report should be considered lower-bound estimates with respect to what has been lost in a disaster. The true cost is likely much higher since the agency has opted not to include some things that are harder to link directly to a disaster: Some of the costs that are not included in the final total include:

Losses of natural capital or environmental degradation

Mental or physical healthcare related costs

The value of a statistical life

Supply chain and contingent business interruption costs

These particular items can be calculated, but their values tend to be more heavily debated compared to something like the cost of a damaged car. If the NCEI were to include the value of a statistical life (VSL), they would need to determine which valuation to follow. Multiple agencies calculate that value differently. It’s also harder to separate out which portions are attributable to the disaster compared to the aftermath of a disaster.

One of the popular concepts that came out of Bastiat’s work is the idea of measuring “the seen” and considering “the unseen.” For the parable of the broken window, the unseen impact is what the money could have been used for had it not been spent on repairs. For hurricanes and other storms, we’ll never know the impact that money spent on storm restoration could have made had the storm not occurred.

The cost of storms also includes the seen and the unseen. It’s easier to see some of the costs through pictures of the aftermath of reviewing government accounting. It’s harder to see what an area would have been like had the storm never occurred, had relief money been spent on something else, or more importantly, had lives not been lost. Those unseen costs also have long-term implications for disaster-heavy regions that are constantly rebuilding just to get back to where they were before the storm.

A Category 1 hurricane has sustained wind speeds between 74-95 mph (119-153 km/h) while a Category 5 hurricane has sustained wind speeds of at least 157 mph (252 km/h) or higher [National Hurricane Center]

Every state in the country, as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, has been impacted by at least one billion-dollar disaster since 1980 [National Center for Environmental Information]

The disasters in 2017 cost a total of $366.7 billion, the costliest since 1980 [National Center for Environmental Information]

The EPA recommends agencies use a central estimate of $7.4 million (in 2006 dollars) to value life regardless of the person’s age, income, or other population characteristics. This would be approximately $11.05 in 2022 dollars. [Environmental Protection Agency]

One other (I think) important factor is that experience of a natural disaster actually reduces the likelihood people will prepare for future disasters. I have a working paper right now examining the sociospatial distribution of disaster preparedness and it is something that is fairly consistent across the US (in and of itself perhaps surprising). Whether the channel driving it is overconfidence or apathy in the face of inevitable destruction, it is something I find concerning. It seems we are missing opportunities at a national level to strengthen communities post-disaster.