How to Think About Your College Major

What the data says about majors and salaries, and why it's not the whole story.

You’re reading Monday Morning Economist, a free weekly newsletter that explores the economics behind pop culture and current events. Each issue reaches thousands of readers who want to understand the world a little differently. If you enjoy this post, you can support the newsletter by sharing it or by becoming a paid subscriber to help it grow:

It’s high school graduation season, which means caps are flying and families are cheering. Millions of soon-to-be college students will also be picking their first college classes. For a lot of those students, summer orientation is less about getting to know campus and more about answering a deceptively simple question: What do you want to major in?

I started my college journey with a major in General Business. I quickly switched to Management. There was one semester when I was double majoring in Management and Marketing. I sure thought I had it all figured out. But in the last few weeks of my junior year, I realized I loved going to my economics classes. I quickly turned down my summer internship and signed up for summer classes so that I could add economics as my second major instead. It’s funny to think that just a few years before that, I knew nothing about that major.

I made all these significant changes to my degree plan at the last minute because I had found a passion for the material. But not everyone makes decisions that way. Some students, and let’s be honest, a lot of parents, look at majors through a completely different lens: What kind of salary will this lead to?

Thanks to the New York Federal Reserve, we have some helpful data to answer that question. Let’s take a look at what the numbers say and what they miss.

College as an Investment

College is costly, and I’m not just talking about tuition. There’s also the time, the energy, the missed wages, and all the other things students could be doing instead with their time. These are known as the pecuniary and non-pecuniary costs of college. So even if someone receives a full-ride to attend college, they still have to give something up to attend.

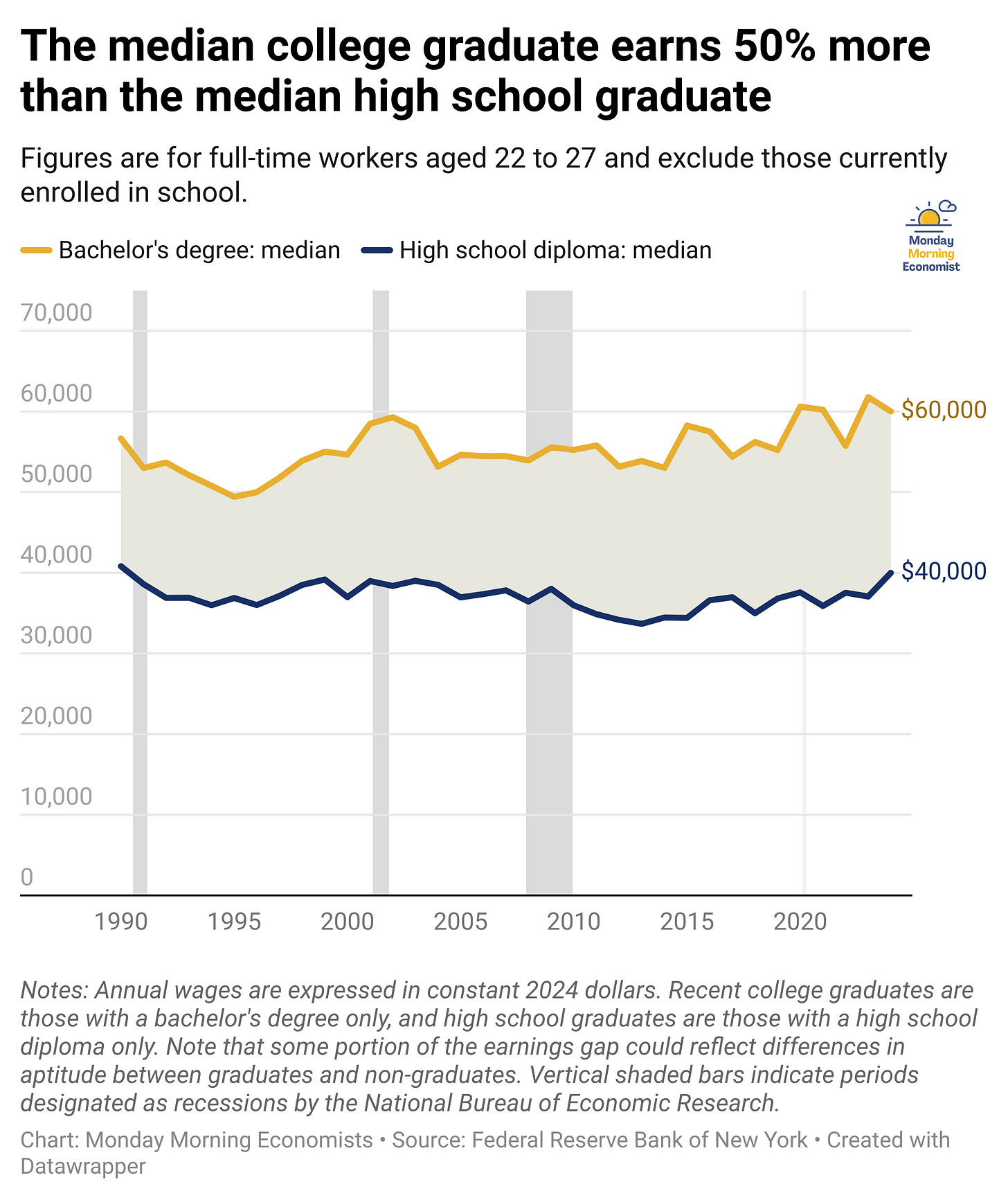

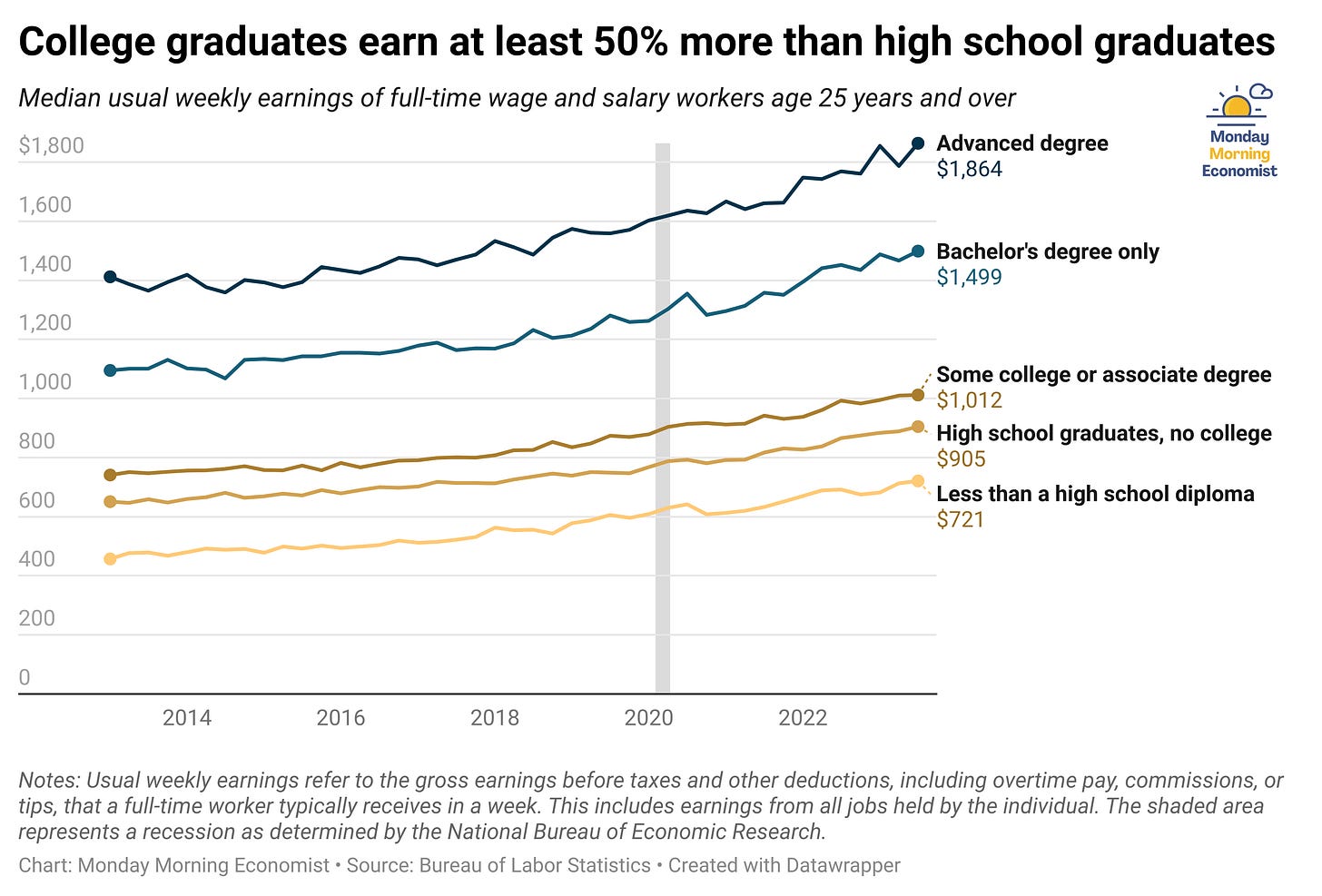

It’s the opportunity cost of college that can be huge, but millions of people make that tradeoff every year. Why? Because college is widely seen as an investment, a cost that millions take on today that will benefit from later in life. But the return that a college graduate earns on their degree isn’t the future salary, which we will talk about more down below. It’s actually the difference between what you earn with a college degree and what you would have earned without one.

That difference is referred to as the college wage premium. Although it fluctuates over time, it has remained remarkably consistent for decades. A young college graduate will earn about $20,000 more than a similarly aged high school graduate, but the typical college graduate earns about $30,000 more each year than someone with only a high school diploma. Over a lifetime, that adds up to a big payoff.

But the benefits go beyond the paycheck. College graduates are more likely to have (and have access to) better health insurance, more likely to report job satisfaction with their jobs, and more likely to have the kind of professional networks that lead to additional career opportunities.

College is a risky investment with a generally high rate of return. Most college students who drop out of school do so in the first academic year. That means they pay some of the upfront cost, but don’t earn the benefits later in life. But college can also be seen as a risk in that the financial outcome depends a lot on what you put in and what you choose to do with it.

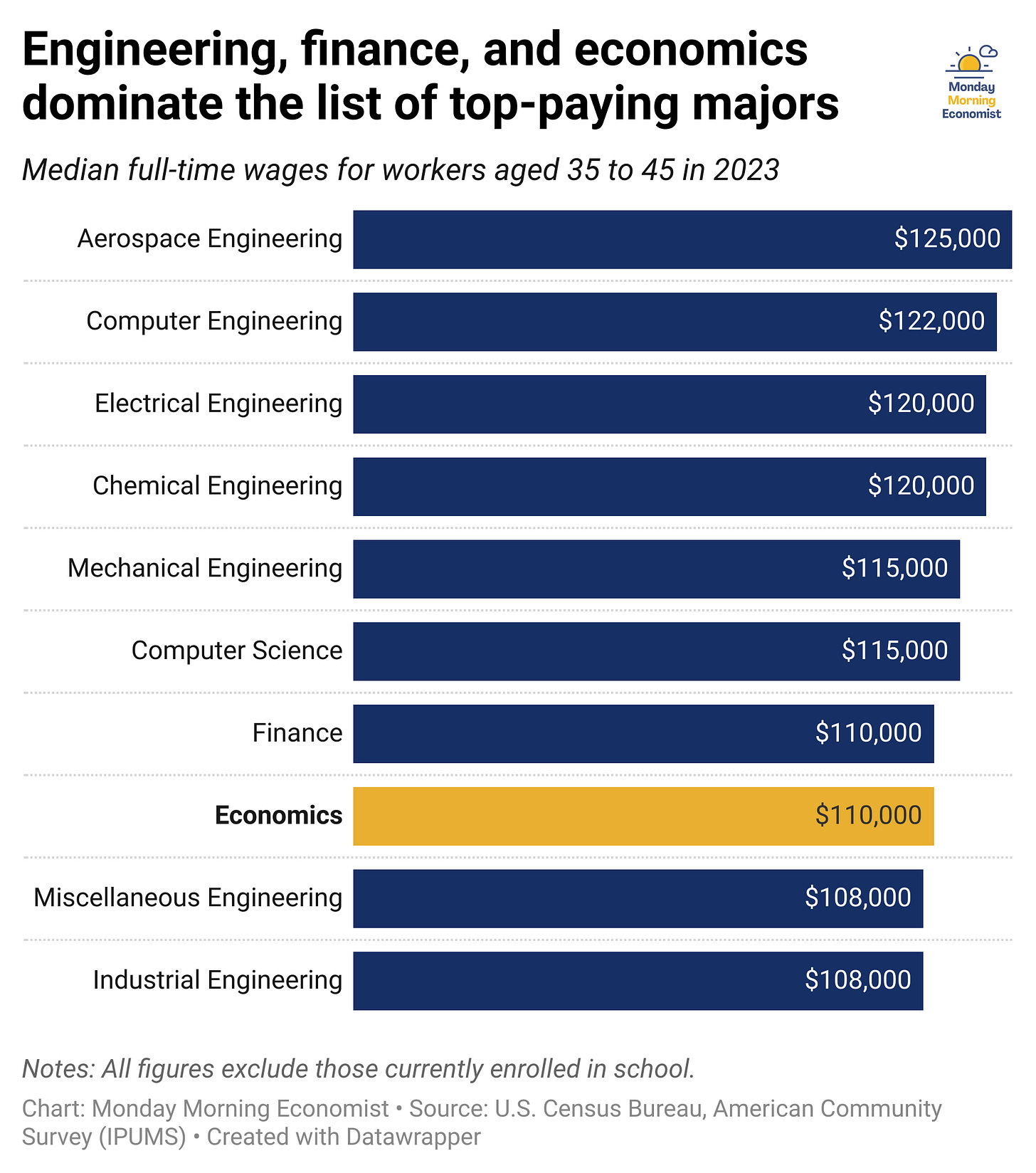

The Highest Paying Majors

It probably won’t surprise anyone to learn that the highest-paying college majors are mostly in STEM: science, technology, engineering, and math. Add in a few business-oriented fields like finance and economics, and you’ve got the top of the earnings chart for mid-career professionals.

But why do these fields tend to pay more?

One explanation comes from a classic idea in labor economics: compensating differentials. The basic idea is that people have to be paid more to do jobs (or, in this case, study subjects) that many others find unpleasant or difficult. STEM majors are often perceived as challenging. They involve more math, more technical content, and more structured problem-solving. If fewer people are willing to do the work, future salaries have to increase to attract enough students to study the subjects.

But that doesn’t mean these jobs are miserable. Plenty of people love working in data, design, or engineering. But it does suggest a trade-off. Some people love the extra work. Others don’t.

The Lowest Paying Majors

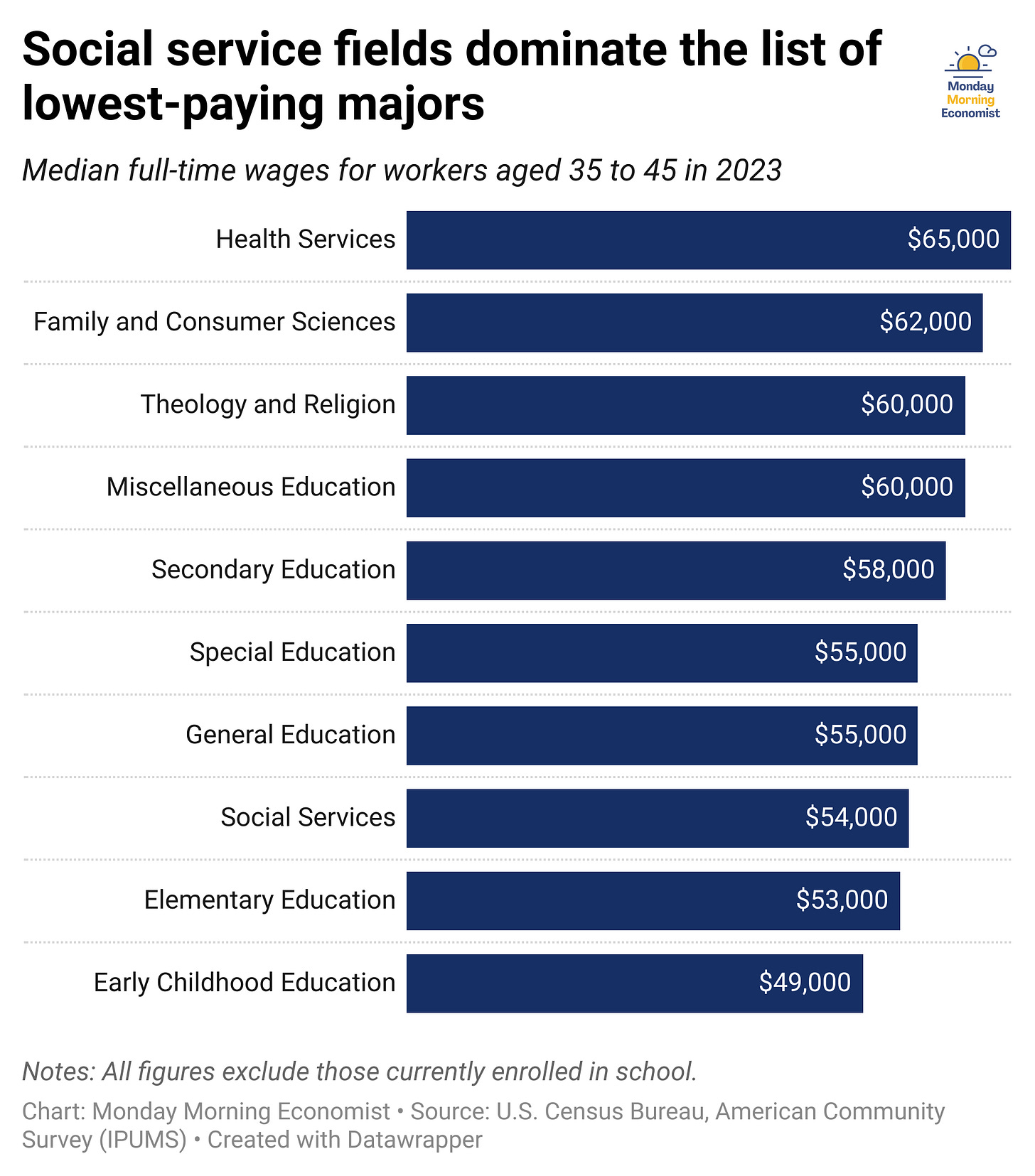

At the lower end of the earnings distribution are majors that often lead to work in education, social services, and caregiving. These include fields like early childhood education, social work, family and consumer sciences, health services, and religious studies. Mid-career salaries in these fields often fall below $60,000, lower than the median for most other college graduates.

But here, too, compensating differentials help explain the data. It will just be in reverse. These careers may pay less than many other degrees, but they offer completely different forms of compensation. People who choose these paths often value the work itself. They’re drawn to helping others, supporting their communities, and contributing to the public good.

It’s not that these jobs are easy. They’re often demanding in ways that aren’t reflected in the paycheck. But for many, the reward comes from knowing that the work matters, whether or not it comes with a high salary.

Final Thoughts

It’s easy to look at earnings data and walk away thinking some majors are “good” and others are “bad.” But there’s another important detail worth remembering: these numbers are based on medians, not averages. In this case, a median would report the earnings of someone right in the middle. Half of the people earn more, and half earn less. That measure is useful because it avoids being skewed by outliers, like the engineering graduates who launched tech startups or the ones who decided to go into teaching.

But even at the lower end of the earnings spectrum for college grads, things may look better than the data shows. The median income for full-time mid-career workers is about $69,000. Only a few of the lowest-paying majors fall below that mark. Those salaries might not sound impressive at a party full of engineers and finance grads, but they’re still good jobs that pay solidly middle-class wages. There are millions of Americans, especially those without degrees, who would be happy to take home that much each year.

Of course, medians can’t tell the whole story. Several high-paying jobs in America don’t require a college degree at all. Trades like plumbing, electrical work, and HVAC repair can be lucrative, especially as demand grows. And on the flip side, not every engineering or finance major is chasing a six-figure salary. My high school calculus teacher was a former engineer. They walked away from a higher salary to teach high school math.

If you’ve made it this far and you’re a student trying to decide what to major in, here’s the advice: pick something you’re excited to learn about. You’re the one who has to sit through the lectures, write the papers, and do the projects. Loving the material makes all of that a little easier.

But if you’re a parent reading this because your child forwarded it, or maybe you stumbled on it while casually Googling “top-paying college majors,” here’s the other half of the message: let your children choose something they care about. They’re probably going to be alright. Because in the end, choosing a major is just one step. What really matters is where they go from there.

Thank you for reading Monday Morning Economist! This free weekly newsletter examines the economic factors behind pop culture and current events. This newsletter lands in the inbox of thousands of subscribers every week! You can support this newsletter by sharing this free post or buying me a cup of coffee!

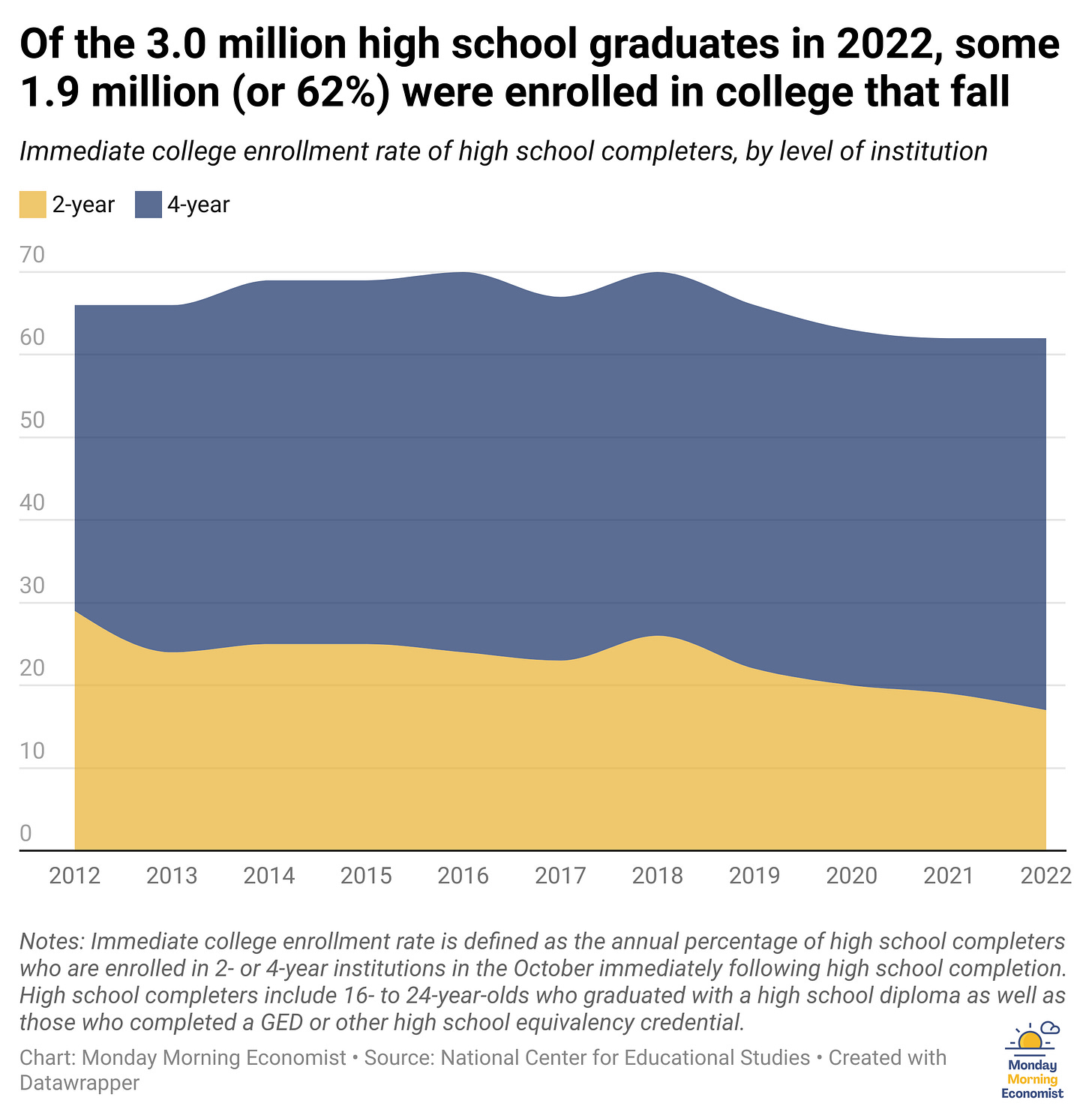

Approximately 63% of recent high school graduates enroll in college the following fall [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

After adjusting for inflation, the average net tuition and fees paid by first-time full-time in-state students enrolled in public four-year institutions peaked in 2012-13 at $4,340 and declined to an estimated $2,480 in 2024-25 [College Board]

According to a survey of students across America, the hardest working college majors are architects, who study outside of classes for an average of 22 hours a week [The Tab]

Postsecondary institutions conferred 2 million bachelor’s degrees in 2021–22, with roughly 58% concentrated in six fields of study: business (19%), health professions and related programs (13%), social sciences and history (7%), biological and biomedical sciences (7%), psychology (6%), and engineering (6%) [National Center for Education Statistics]

The median annual wage for plumbers, pipefitters, and steamfitters was $62,970 in May 2024 [Bureau of Labor Statistics]

Thx Jadrian! This is a complex subject. Although, I think universities need to have this kind of conversation with their prospective students, my sense is they’re not. Just assuming it’s a worthwhile investment without considering the overall costs, the potential future earnings of each degree and the opportunity costs is not sensible. Maybe some colleges are doing this now, but I believe the incentives to do so are low because it’s likely to reduce demand for certain majors and have students/parents consider lower priced colleges or even not go at all.

Great post! You mentioned two things that come up quite a bit when I discuss these topics:

Compensating differential is a factor in the difference in salaries between various fields (for example, overnight workers typically get a shift differential), but I think the much more explanatory factor is simple supply and demand. Fewer people have the type of brain required to do well in STEM fields, while most people can do social work or teach elementary school. This isn't a value judgment on the importance of either career, nor saying that either is without hard work and challenges, only that they're *different* in a way that filters out a significant proportion of the population from one but not the other. My summer job right now is throwing boxes in a warehouse, and it pays pitifully -- but anyone who can fog a mirror can do it. I'm not going to command an engineer's salary while doing something that any guy off the street will do for less, no matter how good I might be at it.

You also mentioned changing majors a few times. My whole life story has been of trying to find the thing that I'm passionate about. High school does not prepare students to choose majors which will set them up on a path to contentedness, rather focusing on ability and potential earnings, with perhaps a nod to "that could be interesting". Even a "day in the life" of various professions is hardly ever discussed, instead showing only high-level descriptions and highlight reels. Plus, what 17-year-old really knows what they love and want to do for the rest of their lives?? I'm a strong proponent of the gap year (or in my case, the gap 20 😬) to give people a chance to experience the world and figure out what they enjoy before investing so much into a college education for it.